Somehow it came to be that I am living in a building where a bunch of rich people live.

I am not rich; I don’t really care that much about becoming rich, as I have always found being motivated by money to be really stupid. I have always been much more motivated by doing the things I love to do and letting money be what it is.

So I find it very interesting that in my 25th year on this planet—and during the time in my life where I am reconfiguring how I look at the monetary value of my time—that I frequently share downtown elevator rides with birds and blokes who pull in staggering amounts of cash.

These people probably pull in 15x what I make a year. It might be true that they work more than me (or maybe they don’t), but ultimately, we all get the same 24 hours in our day, so it’s not like they can be allotting 15x as much time to their jobs.

My qualms about money are that we have made money an absolutely essential part of city life. Creating life is free, giving birth is free, being human day-to-day is free, dying is free. Yet we’ve condensed the entire experience of life into what we can afford, and what we can afford drastically changes how our lives look. What we can afford determines how we feed ourselves, house ourselves and socialize ourselves.

We made up money and now we depend on it.

Growing up, our household felt completely adorned. I remember Christmases where gifts were shoveling out into the hallway and I was always alarmed when other kids said they got one or two things from their parents for Christmas, because my present count was always in the dozens (plural).

Then one of my parents got sick.

Since the last feminist wave sent all the women to work, our economic situation has been rearranged to the point that one person can no longer sustain an entire household with their income. Both parents have to go to work.

When one of our parents can’t go to work, it drastically changes the finances of the household. This is exactly what happened with us.

Christmases were more sparse. There were more questions along the line of, How much does that cost? The bill-paying seemed to be overall more stressful. There were definitely a lot more, No’s.

There was interesting talk around our house regarding money, mostly that we didn’t have enough of it. But it wasn’t that we didn’t have enough money; we had the belief that we didn’t have enough money and there’s a difference.

Whether we have enough money or not enough money is a mental discernment that has actually nothing to do with enough or not enough, and everything to do with our internal value system. If we have enough money to stay alive, then we have enough money. It’s true that maybe we don’t have as much as we would like, but why all the stress about it? How does that get us what we want?

Even though there was talk that money was tight, it never felt like not enough to me. Of course I envied my friends whose mothers drove custom-plated Lexus’ around the neighborhood, but I also didn’t want to be them.

I just wanted to be me.

And for whatever reason—and thank you, Lord, for this and everything that has been brought into and out of my life—I never developed the belief that money was more important than passion.

My passions ran the gamut from novelist, to musician, to actor, to most recently—studying the awareness of movement through yoga.

It’s only ever made sense to me to make money doing these things. Of course I’ve found myself at shitty jobs where my paychecks have been snotty chortles from systems I work for, laughing and spitting into my face: Gotcha now, sucker. I’ve found myself in long stretches of time, supplementing my income at minimum wage joints with no possibility for advancement, because if I got a job with advancement opportunities, then maybe I would take them, and that’s the start of me waking up in thirty years having worked a desk job for most of my life and nothing else.

Instead, I have the distinct privilege of knowing that every head that walks into a yoga class with me means five more dollars, which means that if I go to lunch after class, I will have spent half of what I earned.

And then people look at me and say, yeah, well how are you doing that?

The answer is: It’s not that I’m making a certain amount of money, it’s that I’m more or less okay with what I make.

Let me illustrate this another way:

The other morning, I was getting back to the downtown pad after teaching my morning yoga classes. I was looking forward to the afternoon off, and probably deep into contemplation about whether lunch or a writing session were next in line for me.

There was a yellow SUV Porsche that had followed me into the garage, and I watched him in my rear-view mirror just to see where he was going. He must live in this building, I thought. We’re practically neighbors.

I’m always up for more building friends.

He showed up in scrubs to the elevator, so clearly he had been at the hospital. Doing what? I don’t know, but he had a briefcase dangling from a finger that was sporting a ring approximately the monetary worth of my college education, so I’m assuming, something good. Or at least lucrative.

As he lumbered into the elevator with me, he didn’t make eye contact. It’s not that he was trying to ignore me—the man was absolutely exhausted. His eye skin looked as though it had been accumulating tired apathy for about as long as it takes to accumulate an unreasonable amount of grocery bags under the sink.

And as we rode silently—and then we walked through two doors together, each time with less enthusiasm—it really made me wonder: why the fuck are we doing this to ourselves?

Why are we putting ourselves in situations where we bumble into our jobs for eight hours everyday—like a subscription that keeps getting renewed without our explicit permission—and we develop goals that are financially based? All of this is so we can accessorize our lives with SUV Porsches and downtown apartments and diamond rings that only look valuable but actually are depreciating. Why are we saving money to go on vacations from our lives?

Like, hey, guys—I need a break from the life that I’m currently living right now. I would like to go somewhere and pretend that my life is not completely miserable. Hello, Mexico!

We make all this money so that we can have these totally awesome lives, but in the day-to-day trundle of micro-America, when we actually have our time away from working, cleaning, cooking, and organizing—we sit down and think, man, I’m so fucking tired right now. All of this sucks. So where are these totally awesome lives?

We go on a mission to try and fix it or change it or something, and this turns into us waking up an hour earlier every day just so we can make an appointment to use our bodies, because when we go to work, we sit and slump or stand and slump, but there’s always slumping of some sort. So then we go to a gym and simulate running on a machine, and simulate the motions of working our arms and backs with these other clunking pulley-systems, as if we are using our bodies like they are actually intended to be used.

It’s pretty crazy how easily we resign ourselves to things.

But really what is the alternative to that?

The alternative to that is what I’m doing, which feels like a lot of throwing darts in the dark. If I have to write down my strategy for making money, it is: I do what I like and make money when I can. With a strategy like this, it’s pretty clear why I’m in the tax bracket that I’m in.

That strategy means that I make enough to pay my bills and save a little every month. That strategy means that my disposable income is very limited, and the following terms are not a part of my financial vernacular: insurance, benefits, 401K, investments.

This is why I said that I am reconfiguring how I look at the monetary value of my time: I am looking to strike a balance with my finances to the point where I don’t have to think about them.

Money is an excellent teacher, if we choose to look at it that way. I want to work with money until I no longer feel controlled by it. I don’t want money to determine how I spend my professional time; and I don’t want money to determine what I can and cannot do during my free time.

We can use money to return to neutral: just humanity experiencing living in cities—without the intention to acquire more shit, but with the intention to experience life in absolute fullness.

I’m beginning to come into the perspective that our lives are only and exactly what we believe them to be. This means that if I think something is powerful, it’s only powerful because I believe that. Without me believing in something’s power, it has none.

So if my life is an accumulation of the beliefs that I hold at any given time, then I have every right to reorganize my belief systems to live in a way that feels peaceful and effortless.

It’s not that I don’t want money—I don’t want it to have power over me.

Relephant Reads:

> What Do We Not Understand About Money?

> Money Mindfulness.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editor: Bryonie Wise

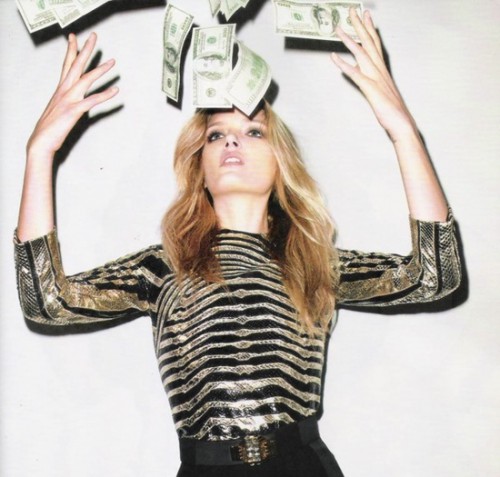

Photo: elephant archives

Read 19 comments and reply