As I sat cross-legged on the cheap grey carpet the smell of Palo Santo washed over me and I felt myself instantly relax.

I sank in to myself and a lazy grin crept onto my face. I’d missed this. For too long I’d been away from home; away from my friends and family, both biological and emotional. I’d been away from my spiritual practises, my routine, and my cat—none of my black clothes had any white cat hair on them anymore, and it felt strangely sad.

This feeling of bliss lasted about thirty seconds.

As the gentle voice leading our meditation guided us to will our body to relax one muscle at a time and bring our awareness back to breath, I was struggling to wrench my leg out from under my butt because pins and needles had turned it into white noise. I tried to do this quietly and gracefully. I failed.

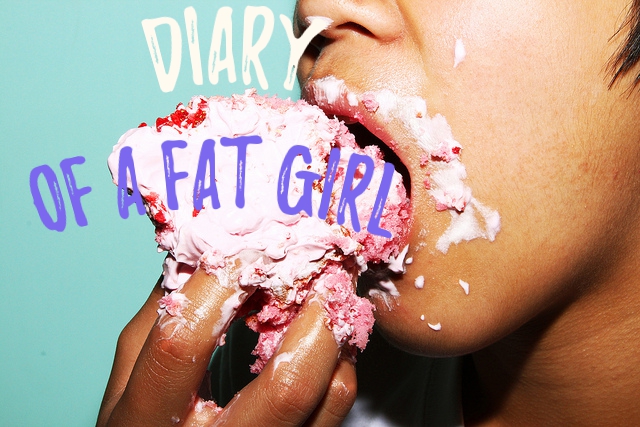

See, the thing is—I’m a Fat Girl.

Yes, that was capitalised. That’s because I’ve been a Fat Girl for so long that it’s now an integral part of my identity.

Girls who were never Fat Girls—or who were only ever lower-case fat girls that grew up into the slender swans we see gliding down the street as if on invisible hover-boards powered by the adoration and social acceptance of others—have no clue what being a Fat Girl is actually all about.

I think these people believe that being a Fat Girl is about binge eating, watching the escapades of Bridget Jones, and shopping at those special shops that seem to sell a lot of sequined tablecloths with head holes cut out of them—and that there’s really not much else to it.

We know quite differently.

When you grow up as a Fat Girl, there’s a moment when it truly sinks in that very few people will ever see past this part of your identity. You learn later in life that this is partly because you developed trust issues too early on, as a result of broken friendships and disappointing romances and the general sense that everyone around you is consistently questioning your worth—after this, you stop inviting people in quite so often.

You learn to be funny, or smart, or arrogant, or all three. These are not necessarily bad traits to develop, but their roots are always rotten. Performing tricks like a court jester, your constant search is one of self-validation. Your message is always “Don’t leave yet, there’s more!” Mostly—and sometimes without even realising it—whatever people want from you, you will give them; and if you don’t know how, you’ll learn. You are a chameleon, hoping to hide in plain sight well enough that no one shoos you away.

You are also an adept liar. This is not because you are a bad person—this is because you are not capable of participating in all the activities that your Normal Girl counterparts do, with relish—and thus need to excuse yourself without anyone clueing on as to why.

You can not, for example, comfortably agree to borrow clothes from wardrobes for impromptu nights in sweaty, messy, wild rooms of music and sticky floors. You can not feel free to wind down the windows and drive to the beach, knowing that when you arrive you will easily slip off your summer dress and allow the sea water to envelop you. You can not reliably take a selfie. You can not wear stripes. You panic as you try to do up the buckle on the plane seat. You will rip stockings—all of them.

You can not be disagreeable, without first preparing your skin for the inevitable physical judgement it will receive as a first port of call, regardless of its relation to the issue.

You can not climb trees. You can not climb anything.

You can not play.

Likewise, you can not indulge—such blatant disregard for your “state,” as your mother calls it, will bring the stares of passing parents, thankful that their children will never end up like you. You must not arrive at family events unprepared; people always seem to want to know—though it is often asked in round-about, implied, ghostly ways—how you got to be like this, and when it will change.

Such a life, with all of its messages and lessons and gifts, inevitably creates some damaged people.

And that’s me. I’m damaged.

So as I disturbed everyone’s peaceful meditation by stretching out my legs—which were squishing their own nerves beneath too many layers of cellulite and unshaven skin—my Fat Girl mentality ran stressfully to the joke centre and whipped up the perfect mixture of sarcasm and self-deprecation, to draw attention away from the faux pas that was my body. It worked, as per, and with a giggle everyone moved on to the next part of the exercise for the night, and this is where the Fat Girl and I turned a corner.

Well, I turned a corner. The Fat Girl sort of rolled.

“Tonight, as it’s the Full Moon and we’ll be bringing things into our lives or manifesting things for ourselves, we’re going to be working with the Fetch Self—specifically, with the Huna traditions of healing your soul.”

For those who aren’t familiar, the Fetch Self is one of three aspects of the soul (or “self”) commonly referred to in a number of Western spiritual traditions, as well as in modern psychology. You may know it as the Id, if you’re a Freud fan.

This part of your soul is also referred to as the “child self,” mainly because it communicates our basal needs—hunger, pain, love, anger, joy, cold, lust. Although it can’t communicate in words (that’s a whole other “Self”), it’s believed to be able to convey needs via symbols and feelings. Likewise, Fetch Self doesn’t understand irony or sarcasm or words said but not truly meant.

Your Fetch Self believes what it’s told. And if we say the same negative things repeatedly, those beliefs can become so ingrained that Fetch Self begins to revolt by attacking the one thing it’s been taught to despise—itself.

The Huna people, who are of Polynesian ancestry, believe that no matter how hard we try to fix the problems we perceive in our physical world, if our relationship with Fetch Self is damaged—if it has been made to believe that it is worthless—our problems will only return. Simple will power can only stave off an infection that severe for so long, but eventually our mind, body and spirit succumb to the undercurrent of sickness that has been cultivated within Fetch.

The Fat Girl in me stopped to listen, and I knew I had some work to do.

I’d decided only the week before that I was going to radically change some things about my health. I’d just arrived back from almost a month in the U.S and, I don’t always have the greatest things to say about Australia, but despite our alarming obesity statistics I had really come to appreciate our lifestyle and all of the opportunities that our geographical placement had given us. After three and a half weeks of eating various combinations of meat, a strange orange cheese, and carbohydrates—the American dream, as far as I could gather—I was determined never to take my extremely lucky life for granted again.

But in that moment, focusing my energy on accessing my Fetch Self, while my shoulders slumped and my back ached from baring the weight of my growing stomach all day, I knew that my initial gusto would all be for nought if I didn’t fix my existential insides with just as much attentiveness and kindness as I did my physical insides.

We invest in gym memberships and meal replacement programs, but how often do we invest those kinds of resources into our soul?

Throughout this series, I want to take a long-term, honest, hilarious, real look at what it means to go against the paradigms of modern Western culture, and treat myself like a sacred object—not in the consumerist driven, fame-mongering way we’re so often instructed to do. Rather, I wanted to question the simultaneous messages of self-idolation and self-destruction that we’re fed on an hourly basis.

This will mean looking at my physical, mental, emotional and spiritual health as an interconnected system. More than that, it will mean exploring and testing a variety of ways to implement self-care.

And it will mean telling the world about the senses of achievement, the desires, the failures, and the shadowy depths of self-worth we try excessively hard to avoid. It will mean sharing unflattering pictures of myself and the effects of my journey. Hopefully, it will also mean inspiration and education for those of you out there who may be struggling, who may be hiding, and who may be desperate to know that there’s someone out there who knows what that feels like—and that we don’t have to feel like that anymore.

So, who am I and why should you care?

I’m a Fat Girl. I’m bruised and hurt. I’m programmed, by a society who at first didn’t know any better and later didn’t much care, to slowly drive my body and my heart into fatal sickness.

I’m 26 years old and about 78 pounds heavier than I should be.

I’m on track to develop any number of degenerative diseases before the age of 55.

I’m over 40% of the Western world.

I’m a product of a culture that we can change.

I’m you, maybe.

And that’s why you should care.

*Tune in tomorrow for Episode Two: So You Hate Yourself and You’re Addicted to Sugar.*

~

Author: Erin Lawson

Images: Original from Flickr/Photo and Share CC ; edited by author

Read 7 comments and reply