We’ve all wondered about the quiet and secretive nature of plants.

Their biomass on land is estimated to be 1,000 times greater than the combined biomass of all humans and other animals. Plants are the most abundant form of life in nature that humans encounter.

However, our knowledge and understanding about these organisms that are all around us is still limited. For a long time, plants were rendered as passive, mute, and insentient entities that look pretty around the house.

Recently, new trends in plant studies have brought forth knowledge about the complexity of plants regarding the processes of learning, memory, communication, and decision making. Terms like “plant intelligence,” “plant behavior,” and “plant neurobiology” have been surfacing in scientific literature and making the headlines of major newspapers.

Some scientists remain skeptical, partially because intelligent behavior in plants is still rooted in the terminology of animal studies. Nevertheless, plants have developed responses to environmental variables that have many parallels to animal senses.

One of the most popular quests in plant research has to do with the sense of hearing. For centuries, plant lovers, amateurs, and scientists have gone out on a limb to answer the following questions: can plants hear? And do plants respond to music?

Darwin was one of the first scientists to test the effects of music on plants by persuading his son Francis to play the bassoon to a mimosa and study the leaves’ reactions. Nothing happened. Darwin concluded that it was a “fool’s experiment.” Since then, hundreds of studies have tried to establish a relationship between different genres of music and plant growth.

In 1968, a series of experiments on the effects of music in plants was conducted by Dorothy Retallack, a professional organist and mezzo soprano from Colorado. Retallack exposed a set of plants to the classical music of composers like Bach and Schoenberg and another set of plants to the rock ‘n’ roll music of Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin. As you may have heard, the plants exposed to rock music didn’t thrive as much as the plants exposed to classical music. In fact, they leaned away from the speakers blasting Hendrix’s acid-rock guitar solos.

These results were published by Retallack in the book The Sound of Music and Plants, sparking great interest among journalists, who published stories with headlines like “Bach or Rock: Ask Your Flowers,” “Mother Is Knitting Earmuffs for Our Petunias,” and “It Shouldn’t Happen to Teenagers.”

Daniel Chamovitz, author of the book What a Plant Knows, describes Retallack’s experiments as a window into the sociopolitical climate of the ‘60s through the perspective of a social conservative who believed that loud rock music was negative and correlated with antisocial behavior among college students.

Retallack’s plant-music research was full of scientific shortcomings, and it was never successfully replicated in a science lab. But the idea that plant growth could be enhanced by sound and music proved to have staying power in popular culture and was further disseminated by the book The Secret Life of Plants by Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird. In the chapter “The Harmonic Life of Plants,” the authors compile several plant-music experiments that build a case for plants’ refined taste in sitar and classical music.

Musicians didn’t stay indifferent to the growing rumor that plants might enjoy their music. In fact, these out-of-the-box experiments with plants gave rise to an impressive sonic journey of artists creating new compositions to aid plants in growing healthier and more luxurious. During the 1970s, it became somewhat common for the local florist to sell “music for plants” records with labels promising fast-growing results and overall happiness for you and your plants.

Such records were often comprised of classical music standards as well as chamber and electronic music, with odes to house plants and music embedded with high frequency tones. These musical cues can still be traced to today’s artists working with plants.

However, the plant’s role in music has changed radically. Instead of being the passive “listener,” plants have become the new composers and performers. Musicians keen on the study of acoustic ecology and bioacoustics have started to develop emergent systems of converting bio-data into sound. These systems allow the translation of electrical signals within the plants into a stream of sounds.

This method of composition is called generative music and was coined by Brian Eno. Generative music is like trying to create a seed, as opposed to classical composition which is like trying to engineer a tree. I think one of the changes of our consciousness of how things come into being is the change from an engineering paradigm, which is to say a design paradigm, to a biological paradigm, which is an evolutionary one.

By transposing plant bio-rhythms into musical notes, musicians can now convey just how complex and sensitive plants are. Monica Gagliano, a plant behavior researcher, argues that by assigning sound to plants’ states, we ought to be careful not to overwrite their natural modes of expression with sounds that are familiar and pleasant to us. In a moment when science is turning its ears to plants once more as new findings in plant bio-acoustics emerge, we must reconsider our long musical relationship with plants.

Music can enhance our connection to nature by making us aware of the invisible life of plants and revealing a hidden territory of vibrational surfaces and an underground mesh of rhythms and communicative patterns. As David Dunn puts it: My intuition is that music does offer clues to our survival.

~

This is an excerpt from Good Things We Learn From Plants, a print documentarium that explores plants through diverse viewpoints and formats including articles, essays, poems, illustrations, and photographs by Victoria Stöcker and contributors. Readers may learn about space gardening, the world’s tallest trees, a mobile greenhouse, native flora, plant music, and more. This excerpt by Patrão is the introduction to a 12-page compendium on music for plants, music about plants, and music by plants. Discover more by purchasing a copy from the shop.

~

~

Author: Carlo Patrão

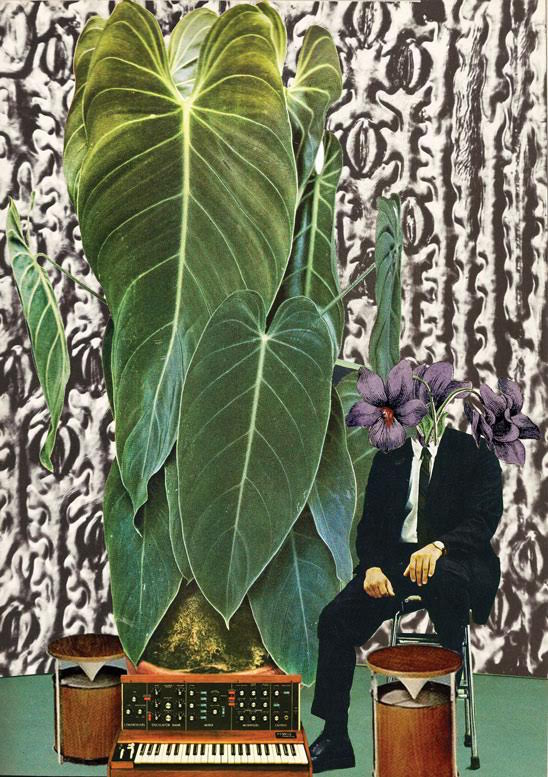

Image: With permission from Evan Crankshaw

Editor: Callie Rushton

Copy Editor: Yoli Ramazzina

Social Editor: Waylon Lewis

Read 0 comments and reply