It’s been 12 years since I left my job as assistant editor at a small-town newspaper, quickly putting as much distance as I could between myself and the drab, windowless newsroom where I’d toiled—sometimes up to 18 hours a day—on and off for five years.

I compared the job to an abusive lover: it would beat me down with its long hours and pathetic pay until I finally left, only to woo me back again.

I was in love with that job. But damn, it hurt.

Unlike many who come to remote communities to hone their reporting skills, I’d been living in the mountain town of fewer than 10,000 people for several years before finally deciding to put my journalism degree to use. I was invested there. I owned a home. I knew the players and their stories and the community’s history. And while that was important to my editor, it mattered little to those managing the bottom line at this corporate-owned weekly newspaper.

In the time I worked there, the number of newsroom staff dwindled. Workloads increased. Pay stagnated. We stayed up late covering town council meetings on deadline, got up early to report on birding expeditions, and sat tearfully through heart-wrenching court hearings involving sexual offenders, violence, and DUIs in our otherwise idyllic community.

But here’s the thing: no one else is reporting this stuff.

To say there’s a crisis facing the news media industry is like saying that Clark Kent was alright looking and fairly fit. But what no one’s talking about is how that crisis is affecting small-town newspapers and the communities that depend on them. While there are multiple sources for national and international news, local newspapers are the only ones covering small-town politics, bake sales, and art gallery openings—and are often mined by larger media outlets relying on community newspapers for on-the-ground reporting.

According to researchers at the University of North Carolina’s School of Media and Journalism, “a new type of newspaper owner has emerged, very different from traditional publishers, the best of whom sought to balance business interests with civic responsibility to the community where their paper was located.”

They describe corporations as the “new media baron” and the swaths of defunct newspapers left in their wake as “news deserts,” estimating that up to 85 percent of news that feeds the democratic process comes from community newspapers:

“As a result of these dynamics, many smaller cities and towns could lose their local newspapers and with them the reliable news and information essential to a community’s economy, governance and quality of life.”

Corporations buy up floundering newspapers and suck the life out of them by slashing editorial budgets while continuing to reap advertising revenue. They reduce newsroom staff, cut wages, and increase workloads. Fledgling reporters don’t stick around long enough to understand or value the communities they serve and if the investment isn’t profitable, newspapers are shut down altogether.

Since 1999, corporate ownership of community newspapers rose from 38 to 66 percent in Canada, and in the U.S., those owned by investment corporations rose from 20 percent in 2004 to nearly 50 percent in 2014. In November, two of Canada’s largest media conglomerates swapped more than 40 community newspapers, shutting them down to effectively remove competition in communities across southern Ontario.

“You need two competing papers to keep everyone on their toes and offer the community different takes on stories and coverage,” says my friend Pam, a professional photographer who spent nearly 30 years working in community news before going freelance. She’s seen the industry go from treating photography as an art, with dedicated darkrooms and full-time photographers at each paper, to handing reporters a point-and-shoot digital and asking them to come back with an image.

Those reporters are also expected to be social media managers and videographers.

For anyone still harboring romantic notions of newspapers existing to report the news, let me introduce the newshole: a paper is laid out with the ads placed first. What remains are the holes to be filled by newsroom staff. As long as they’re still selling ads, quality content matters little to the powers that be. Ever notice content from other regions plunked into your local newspaper? We can thank a corporation for that—anything to fill that pesky newshole.

So, when we’re feeling frustrated with the quality of our local paper, here are a few things to consider:

>> Reporters are likely inexperienced. Weekly newspapers don’t pay enough to support seasoned reporters. The person with the most important communication job in your town is probably fresh out of school and looking to gain experience.

>> Reporters are often overworked. When I was in weekly news, it wasn’t uncommon to work from 8 a.m. until midnight on deadline. My editor regularly slept under his desk. Keeping that kind of schedule doesn’t lend itself to accurate reporting, let alone a healthy lifestyle.

>> Reporters aren’t always invested. Small-town reporting gets interesting once you’ve spent a few years doing it and gotten to know the players. Most community newspaper reporters don’t stick around long enough to understand a town’s complexities and history.

It’s important to remember that small-town news reporters aren’t incompetent or uninterested. They’re often just busy and inexperienced—and a little understanding from their community can go a long way.

Here’s how we can be proactive in making sure local news gets reported and community newspapers can survive:

>> Welcome new reporters. Make an effort to get to know newspaper staff. Take them out for coffee. Sit down with them. Help them understand the issues. If you’re a local newsmaker, make yourself available as a source.

>> Be respectful. You don’t need to love the company to accept that the people who work there are community members, just like you. They’re not getting rich from what they do; it’s a labour of love. Help them out and teach them about your community’s history, its concerns, and what’s important to residents. Be a reliable contact they can reach out to.

>> Write letters to the editor. A newspaper editor will never complain about a well-written letter to the editor. If your paper got something wrong, write a response that respects differing viewpoints and our human ability for error. It’s the most effective way to get your message to the community.

>> Support independent media. Whether it’s online or print, what our world needs now is people, on the ground, reporting on issues. If there’s local, independent media you respect, show them some love. Buy ads. Buy subscriptions. Be a reader. Be a writer. Be willing to pay for it—it has value.

>> If you don’t get involved, you can’t complain. There’s nothing worse than having the source who didn’t call you back criticize your story. Remember that reporters are often busy and working on deadline; find out when that deadline is and offer a half-dozen ways for them to get a hold of you last-minute, if needed.

The paper where I worked slowly dwindled and vanished, amalgamating with another paper down the valley. I’ll never go back, but I respect and support those who continue to report on small-town happenings. Their work is vital to our communities and our democracy.

~

~

Author: Amanda Follett Hosgood

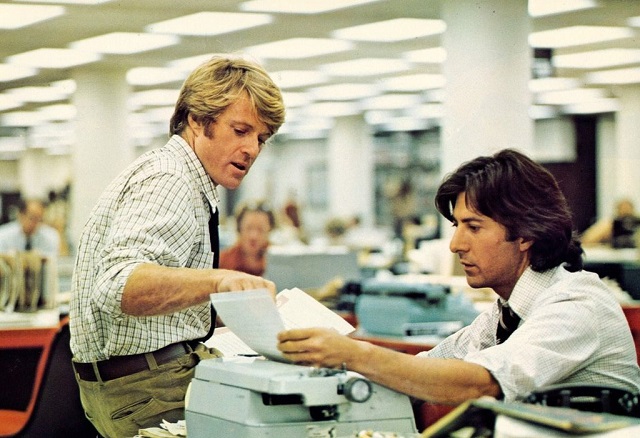

Image: “All the President’s Men”

Editor: Nicole Cameron

Copy Editor: Callie Rushton

Read 0 comments and reply