I used to live in the highly politicized atmosphere of Berkeley, California, where few conservatives exist (or let it be known if they do). The traditional power struggle there has not been between left and right, but between moderate liberals and progressive leftists. And that struggle was often as bitter as the more conventional one. A burg full of self-avowed pacifists is not necessarily a peaceful place to be.

From within the leftie cocoon of Berkeley, the rest of the world was seen as a hopeless morass of regressive social attitudes and backward politics… and this was well before the age of Trump.

Coming from North Carolina, where I’d never really felt at home despite being born there, Berkeley attitudes were both a cultural salve and a continuing source of amusement. It felt more like home, if sometimes a surreal one. But the environment began to feel less welcoming when the health crisis of my thirties led me from youthful political preoccupations into a more spiritual state of mind. That divergence came to a head when I did a Berkeley bookstore reading for my first solo title, A Little Book of Forgiveness (released in a sixth edition in 2017 as THE FORGIVENESS BOOK).

At the end of the reading I took questions from the audience and soon found myself confronted by a classic Berkeley haranguer. He lit into me for espousing a passive, regressive attitude that would encourage people to ignore the political realities of the day, and sink into a touchy-feely state of self-absorption. At the end of the day, he let me know, I was “part of the problem instead of the solution.”

If Berkeley had ever believed in the death penalty, that’s the kind of verdict that could get you hung from the rafters.

Somewhat taken aback and unused to handling hecklers, I sheepishly admitted that I didn’t really have an answer to his challenges, and that part of me was even tempted to agree with his damning analysis. On the other hand, I knew that the path of forgiveness had saved my life and sanity, and I hoped that what I had written would help those who sought guidance on the same path.

At that point the score in my head read: Haranguer 1, New Author 0. But then an instinctive curiosity took over, dissolving my unease, as I asked my questioner directly:

“So what are you doing here? Why did you even come to the reading of a book about forgiveness?”

Now it was the haranguer’s turn to feel uneasy. He looked flustered and mumbled, “I don’t know really.” Then he shrugged his shoulders and sat down.

In the ensuing years I’ve coached individuals, spoken in public, and conducted workshops about forgiveness many times, and never run into another haranguer. But I have had plenty of opportunities to observe individuals reacting to the idea of forgiveness with suspicion or outright hostility. Reactive attitudes vary, but there are at least three common styles:

My enemies are real and you’re not taking them away from me. Whether one’s perceived enemies are political (liberals or conservatives, Americans or Russians, Israelis or Palestinians, Middle Eastern terrorists or Western oppressors) or personal (my ex, my parents, my siblings, the neighbors) it can be devilishly difficult to let go of the notion that someone is out to get us, and strong defenses must be maintained against all perceived enemies. The U.S. is awash in guns for this very reason, and has a chief executive who thinks that a giant wall is the solution to enemies encroaching from one direction.

In fact, it is not unusual for individuals, groups, organizations, cultures and nations to define themselves partly by whom they defend themselves against. This is what I call “self-esteem by negation”, i.e., I’m clearly better and more worthy than all those who are trying to destroy me.

Genuine forgiveness — which must be universal to be meaningful — requires the courage to love one’s enemies, while remaining realistic about who they are and your history with them. Gandhi alluded to this profound challenge when he said, “To forgive is not to forget. The merit lies in loving in spite of the vivid knowledge that the one who must be loved is not a friend.”

Forgiveness will just open me up to more abuse, and I’ve had enough. This is a common belief among those who mistake forgiveness for the attitudes of giving up, giving in, and accepting attack, loss, or sacrifice. Over years of study and practice, I’ve found just the reverse: that a disciplined habit of seeing things through the eyes of compassion is the key to a strength that far surpasses self-defense, wariness, or competitiveness. This strength derives from learning to recognize that we are in charge of how we experience all circumstances, negative or positive, and how we experience every kind of relationship.

Over time, a forgiving attitude also sharpens one’s perceptions of human frailty. You become more sharply attuned to signs of danger or likely abuse, not less. You also develop faster and more effective responses. These capacities come about as you recognize the deep common source of all human suffering and begin to heal it within yourself. That suffering is the belief in a fundamental separation from love — even if one fervently “believes” in love, and especially if one is constantly searching for it.

Everything is perfectly fine, I’ve forgiven everyone I need to, and I don’t want to hear any more about it! This attitude is a thinly disguised anger hiding the fact that hardly anyone has really been forgiven, particularly oneself. While many people think of forgiveness as a way to heal or get past problems they have with particular people, it is really a discipline of seeing the entire world differently — through the eyes of acceptance and compassion rather than wariness and judgment. That’s a profound shift of perception, because it can literally mean giving up the world we’re accustomed to.

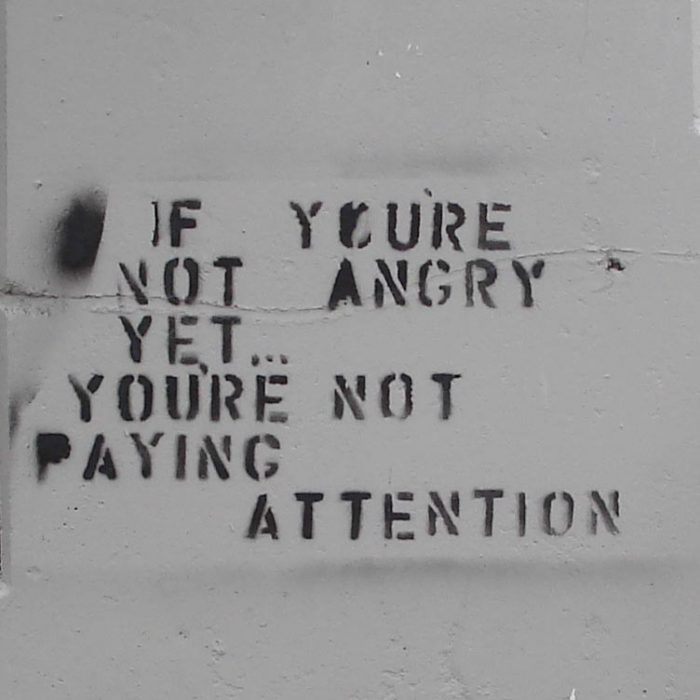

If we’ve depended upon the world to furnish us with the enemies, anxieties, and resentments by which we define ourselves, then forgiveness means progressively dying to all that. And few of us will give up our anger at this world without a fight.

“What was that again?” by mag3737 is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Read 0 comments and reply