~

When I was living in Nepal 10 years ago for voluntary service, I stayed with a Nepalese family (which is now kind of my second family).

When my father from Germany came for a visit, my Nepalese mother took me aside, stared knowingly into my eyes, and said calmly in Nepalese:

“Your father looks sick, Sarina”

I didn’t take it seriously. I thought, because of his thin but muscular features, she must have seen a resemblance to people from the Nepalese labor class.

Maybe I was right, but maybe she had seen by then that there was a tumor growing in his body.

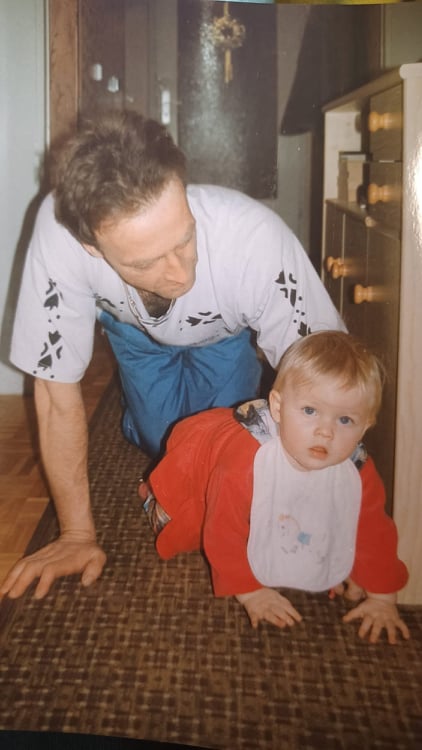

I can still see the worried, soft eyes in front of me. The tiny kitchen in which we were eating a classical Nepalese Dhal Bhat with veggies from the garden, the breeze and noise of the ventilator that helped us bear the heat of summers in the south of Nepal, the dirty dishes that I started to clean. The surprised look on my dad’s face that I did the dishes.

No matter if my Nepalese mother knew or not, she was right. Only six months later, when I had already returned to Germany, my father called me in order to tell me that the doctors have found cancer in his body and he needed treatment. It was urgent.

Around one year later, he died.

I sat next to his dead body, in which still some aliveness seemed to dwell. I kissed his forehead, and somehow, there was a long exhalation that let his body tremble one last time. If there is such a thing, maybe that was the moment when his spirit left.

He was everywhere in this hospital room—his being infinite and still close to that body that he lived in made my awareness widen. There was so much peace and stillness and spaciousness and also that, which I called love.

With his death, all that I held on to that didn’t really matter died as well. Halfheartedly, I tried to attach to some aspects of my identity, but I was simply too exhausted to do anything but surrender to this confused, wide space beyond the layers that I built. It woke me up. Literally, I felt incredibly energetic and alive.

I was present and clear organizing all those little bureaucracies for the funeral and celebration after (on which only my friends accepted the invitation to wear colors and have fun and were looked at suspiciously). I was guided by something the following few weeks. I simply knew what to do. I somehow even figured out all his computer/email passwords, as if something was whistling them in my ear.

I don’t think many were able to mentally understand what I was doing and saying, but somehow most were intrigued by the unique and obscure way I chose to react to the death of my father. Even the priest didn’t understand me when the words, “He chose to leave on a ‘soulish level’” left my mouth. He thought it was suicide, but that was not what I meant. In my father’s eyes, when I last saw him was our final goodbye, and the way he spoke showed me that he was about to step over.

In my purple glitter dress, I went in front of the catholic church and held a speech about the spiritual process he, as a nonspiritual person, went through.

There is a moment to end a fight, isn’t it? And sometimes surrender can mean death. Or in my case, surrender meant waking up to life.

The process he went through in the last two years of his life was like a proper guideline of graceful living and dying. And here is an insight:

Graceful dying

“It is how it is” was what he always said with a sweet grin on his face—even days before he passed away.

My father had an armor that let him appear to be a robotic villain sometimes. He was often absent and lost in his work. Cold. His moods swung, but it was obvious that he felt he was caught in this life. With life, I mean our heavy and tiring family dynamics.

He once said, “One needs to choose Family or freedom.” I disagreed. When he came to Nepal, it changed some buried beliefs within him that he could experience family and an adventure in Nepal at the same time. An old concept died.

“He’s different, Sarina, so excited and joyful,” I heard from other family members.

It seemed, as he was a teacher for me, I was one for him as well. He was suddenly able to see me, his daughter, as an equal and really listened to me.

I had told my parents only one month before the departure to Asia that I was about to leave. At this point, I just felt like escaping and I had found a way. I knew I would never come back to live with them.

My father first didn’t react at all. He was sitting there on his desk, looking in my direction, nodding, and then focusing back on his work. I felt a pinch in my heart, but much more anger.

I’ll finally be gone from here.

When I returned from school that day, I couldn’t believe what he had done. There was a huge map of Nepal printed and pinned to a wall. Two little dots were placed on the city where I was about to shift. I felt him observing me, examining his gift. He smiled silently when he saw how touched I was. He had instinctively figured out my love language. A little later, he even understood a second love language of mine: he was hiding gifts in my room, which I wouldn’t have accepted directly.

We weirdos understand each other.

When he, the man I had never seen crying, dropped a tear and didn’t let me leave his hug when I said my goodbyes, I trusted his love for me that had found a window through his massive walls and through mine. I feel it was because I was showing him that there was a way out of a dynamic both of us hated. I think he felt relief as well—that I wouldn’t rot in that golden cage anymore.

The tumor might have already been there.

One year later, when I started to study in university, even though my heart was still in Nepal, he started chemotherapy. I was impressed how he was able to organize the demolition of all that he had built up the last 30 years. He slowly gave up his clients and finally closed his company. And instead of losing himself in pity, resentment, or grief, he imagined an alternative life. It was a relief to have a legitimate excuse to leave this life behind.

He started to dream again.

He imagined traveling and living in a van for a while. He even accepted the artificial bladder that he had got after one of many surgeries. He was joking that it was easier now to pee during a long car ride.

I was the only one who laughed.

With dreaming, he created an inner safe place that made him calmly be with all that was happening. It didn’t matter that none of the dreams became reality for him. For me, yes—I carried him with me around the world and lived in his van.

While he dreamed about us traveling with motorbikes in Nepal and India, his tumor spread. Surgeries followed. The doctors wondered how he was still alive with those vitals. It didn’t make sense medically, but he simply was. And because there was nothing else to do, he laughed playfully and shook his shoulders. I think he felt a little proud of the superpowers of his body.

There were two moments in which it seemed like all tumor cells were gone. We had a brief rest in hope and relief. But honestly, I didn’t trust that stillness. I just felt that death was still around.

And every time the harsh backlash followed and the metastases spread until they were everywhere, he told me about it, each time in a calm accepting voice. “It is how it is.”

The tumor finally ate his body. One leg was swollen due to water retention, while the other one was skinny and fragile. It looked obscure, not human anymore. He decayed, while his soft, blue eyes were watching me, kindly checking if I could bear his body dying. I will never forget those looks.

With me, he was able to make morbid jokes about the death that was lingering, about being still alive in a body that was dependent on machines. We shared laughter, but also the silence after. A wordless space.

We knew.

Step by step, he let go of all that he was attached to. His armor fell. And what was the Nepal map and timid smile two years ago were long hugs, and huge, goofy smiles now. There was unconditional love in his eyes.

This tumor had brought him to an inner place of peace and it pulled me in as well.

And then he died.

With his death, I, equally armored, broke open. My heart cracked so that I was finally able to feel. And I was falling in love with life.

All that was numb—that I had abandoned—rippled to the surface. I finally could feel—intense, yes—but so alive.

With being vulnerable and shyly rediscovering life, I attracted people I really longed to connect with and places that nourished my heart and soul instead of feeding my ego. I existed without knowing what I was, because what I played before was a show and I noticed what I was attached to (in an unhealthy way), and let it be buried with him.

He had been with me for the next years and somehow became a guide, directing me when I fell into old patterns. But much more importantly, there was this profoundly accepting voice inside me:

Surrender. Trust. Dare to fall. You will land where you belong.

His death was not graceful—his dying, though, was.

Of course, I miss the dad I had for two years whom I never had when I was a child. But I wouldn’t change anything if I could, because I know in my heart that his death was the gift for my soul to wake up to life and for his to heal.

Thank you, Papa, for your last gift.

Read 18 comments and reply