Growing up, most, if not all of us, heard the phrase, “Don’t call people names.”

Even if the admonition was not directed at us—because we were angel children who presumably never did anything wrong—we heard someone else get this directive.

It’s not one that can truly be debated either. As we grow up, we can probably logic away the idea that “if you don’t have anything nice to say, then don’t say anything at all.” Though we know that the spirit of the idea remains accurate, the hard truth is that we sometimes must say things that are not nice to be truthful.

Sometimes we need to stand up for what we believe, to engage in debate—although that just becomes a semantics argument about what is “nice” and what is not.

So yes, it’s not as though all the rules we were given as children still stand, but some do—or at least should.

And name-calling—well, that’s a bit harder to justify.

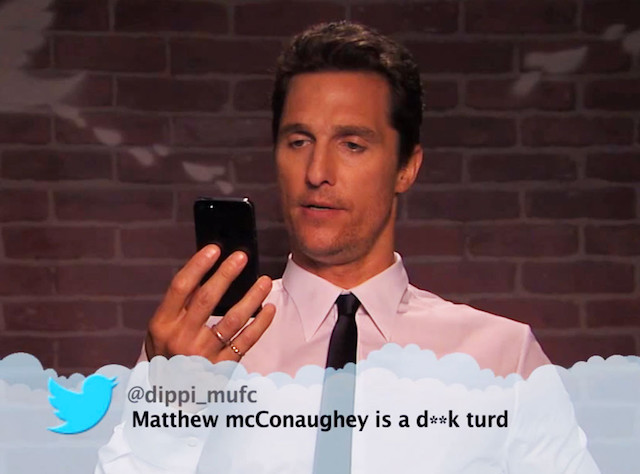

While experts state that name-calling is a normal part of a preschooler’s development, much past that age, it’s not healthy, nor is it constructive. Does this seem obvious? Apparently, it’s not. It’s come back into fashion for adults—or maybe it was always in fashion and is simply more obvious now that it’s online for everyone to see.

@katyperry must have been drunk when she married Russell Brand @rustyrockets – but he did send me a really nice letter of apology!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 16, 2014

Even before the presidential election and inauguration, name-calling was not hard to find on social media, on Twitter and in comments sections in particular. But now, it’s seeping into our online lives like never before. I’ve seen family members—who must think I can’t see what they post on other pages—call people dildos. Nice, huh?

When we parse it out like this, it’s clearly a ridiculous and childish thing to do. When we’re on a Facebook page reading an inflammatory article about others that bolsters are own beliefs and the comments section is filled with other people doing the same, we feel not only justified, but righteous. We’re doing something right by putting the accurate label on someone.

But the truth is, Graham’s Hierarchy of Disagreement lists name-calling as the lowest form of argument.

And when it comes down to it, the context is not really important. What is important is that I’m referring to grown adults. Let’s face it: Anyone on Twitter or Facebook we’re getting into political arguments with is probably far enough past the formative preschool years where name-calling hasn’t been “okay” for quite some time.

On Twitter recently, I saw a grown man (or so his bio said) call a thirteen-year-old in a wheelchair a “dummy” (the kindest of his comments). I’ve seen people throw around “racist” and “Nazi” like they mean nothing. I myself have been called a “liberal elite” in the same tweet that I was also called a “moron.” I have also been called a “c*nt” and a “b*tch” as well as a “snowflake,” a “libtard,” and a “feminazi.”

Frankly, it’s not the names themselves I’ve been called themselves that are really the biggest problem. It isn’t the fact that name-calling can hurt people’s feelings. It isn’t the fact that it truly is the lowest form of argument that has been proven to have more to do with our own feelings of inferiority and inadequacy.

The real issue in our current culture is what name-calling does to our own brains. As anyone who has been through a yoga teacher training or read some of the yogic texts on identity knows, we believe the stories we are told. We believe things about ourselves that we’ve been told or that we’ve told others our whole lives. If we’re laughed at as children when we’re trying to learn, we label ourselves “nerds” or we think less of ourselves for “always having our nose in a book.” If we’re told repeatedly that we’re “just not good at math,” we often don’t try to break out of that mold and get better.

When we repeatedly tell ourselves (and anyone else who will listen either in person or online) and listen only to the views of people who reinforce those opinions, we start to believe those stories—whether they are true or not.

I have zero idea about what we should do about the current culture in the United States that is so full of vitriol. There are experts out there who, hopefully, have better ideas than I on how to reunite the country. What I do know is that it does bother me to see family members on Facebook state that “all these snowflakes are morons.” It bothers me when someone on the left says “all Republicans are morons, what do you expect?”

We are all, within each of those groups, different. We are not all the same just because we generally have similar political leanings. And we all know this. So why is it so hard to stop ourselves from labeling an entire group? Why do we give in to playground bully tactics?

We can’t fight all the battles on all fronts, but we can start small. It’s time we start questioning the echo chambers we engage in, which only serve to tell us we are right in our thinking instead of challenging us to see things from someone else’s point of view.

It’s time we stopped acting like the Internet gives us protection to act in ways we would never consider acting to another human in real life. At this point, the Internet is real life, and we can all start to repair this rift by doing what our parents and teachers told us—what we all know, deep down, is the only decent decision, and what we tell our own children to do: to stop name-calling.

Even if you can’t do it for others, do it to not undermine your own arguments, to not give in to your own insecurities, and to not limit your own thinking.

Author: Gretchen Stelter

Image: Youtube

Editor: Callie Rushton

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply