“Lori! You didn’t make the coffee!” I shouted from the kitchen, staring at a French press containing only dry grounds.

“I know!” she shouted back. “You were the one who offered to make it.”

What the f*ck?! It was about 11 in the morning and she and I, along with a friend, were working on a project in the dining room and I was in serious need of more caffeine.

Earlier, I had announced that I was going to make some more coffee and asked if either of them would like some. They nodded, “Yes, yes please.” So, I went to the kitchen and filled the kettle with water, placed it on the burner, and turned the gas flame to high. I cleaned out the old grounds from the press then ran fresh beans through the grinder for a new batch. I put the grounds in the press. There was only one step left: pour the hot water into the press when it was ready.

I returned to the dining room to rejoin my wife and our friend. A couple of minutes later, my wife got up and went to the kitchen.

“John,” she called out, “the hot water is almost ready, I’m going to take it off the heat.”

“Oh, yes, yes please!” I replied, happy she was saving me a step. I was really looking forward to, and needing, that next cup. After about five minutes—just enough time for the coffee to have properly brewed in the press—I got up and returned to the kitchen in anticipation only to find, to my dismay, no coffee made. All I found was the kettle of water, now cooling on the stove, and the same press with dry coffee grounds.

I stood there in disbelief. My wife was just in here and turned off the burner. Why in the world would someone turn off the burner and not take the next step? There was only one reason for the hot water and that was to make the coffee. Anyone should know that the next obvious thing to do is pour that hot water into the French press!

It was a small thing, but it still made me mad. And my anger felt justified, at least to me, in that moment. After all, she said that she was going to take care of it, but didn’t to my estimation, and now I’d have to wait again—at least another 10 minutes or more.

I cursed again under my breath, turned the burner back on, and returned, with no coffee, to the dining room. I was steaming and trying to hold it in at the same time in front of our friend.

She could tell I was mad. “I really thought you said you were going to take care of it,” I said to her through clenched teeth.

“I did,” she replied. “I took care of the hot water. I turned off the stove. You said you were making coffee so that is what I thought you were going to do right after. I wondered why you took so long to go back into the kitchen.”

It was one of those moments of simple yet profound awakening. She had actually done exactly what she’d said she would. Nothing more, nothing less.

In my current job, I work with teams and leaders. A recurring theme is communication—specifically, the conversations that are missing and the lack of good, clean, precise language.

Making coffee is a pretty simple task and there are not that many ways it can go wrong. It’s either automatic drip, or a French press, or maybe one of those single-serve types. Sure, espresso is more complicated, but the science of coffee has been worked out and we all mostly know the fundamentals. And yet, breakdowns are still possible.

And if breakdowns can occur in the simple task of making coffee, it’s easy to see how breakdowns can occur in practically every other aspect of human behavior, especially when more than one of us is involved. It happens between friends, lovers, spouses, parents and children, co-workers, and so on.

If there is one thing that separates us from the rest of the animals, it’s our ability to create abstract concepts in our brains and then share them with others through language. We’d better get that right, more than not. But in our modern world, there are so many things competing for our attention that simple communication can be trickier than we think, which leaves us to make assumptions and conclusions about our fellow humans’ desires and intentions. Which is exactly what happened when I jumped to a conclusion about the task my wife was offering to do.

It’s an ongoing battle, but here are three tactics I practice to improve any conversation I’m in:

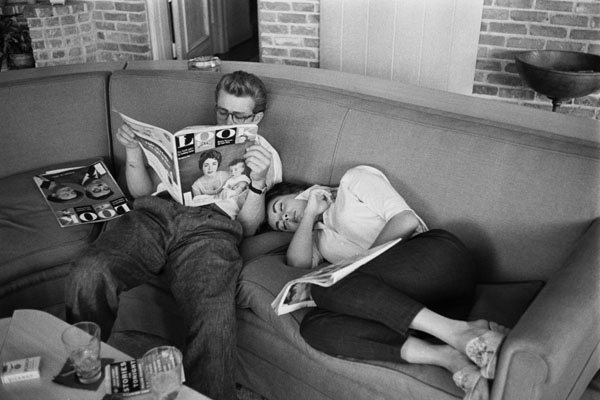

1. Remove distractions. There are times when I am reading or writing or checking my email, and my wife will start to share some important information about the day. It is really easy to keep on reading or writing or doing email and then instinctively reply when she finishes, “Okay, got it.” Which, I really don’t.

Over the years together, I now try to catch myself and do one of two things: a) stop what I am doing, turn and look my wife in the face, and ask her to start again, or b) stop what I am doing and ask for 5 or 10 minutes to finish what I am focused on so I can give her my full attention. She gets it, and it usually helps.

2. Get clarity on the desired outcome, or be clear on the conditions for satisfaction. In our personal or professional lives, unspoken requirements or desires can create everything from missed deadlines to waste and rework, or damaged relationships. Scanning for where unspoken assumptions might be in a conversation is essential. Making them explicit is difficult but necessary.

There are plenty of strategies out there for this. Books like Crucial Conversations or Fierce Conversations, to name just two, attempt to get at this problem. But the first step is to be aware that assumptions exist in our conversations all the time.

3. Develop a centering practice to use before difficult or complex conversations. Our brains are energy hogs—they consume 20 percent of the calories we take in. When our emotions get in the way of healthy communication and decision making, it makes communicating effectively even more difficult. A simple practice of taking a few deep breaths before a difficult conversation with your spouse, child, or a co-worker, can be a game changer.

In addition to these three tactics, it’s also important to practice self-care. We will say the wrong thing or act incorrectly on assumptions from time to time. It’s better to identify the error and work to correct it rather than beat ourselves up.

~

Bonus: The One Buddhist Red Flag to Look out for.

~

Author: John Robinette

Image: Scio Central School Website/Flickr

Editor: Nicole Cameron

Copy Editor: Catherine Monkman

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply