I was born in the apartheid years of South Africa.

Apartheid is an Afrikaans word for “apartness,” and this system was legislation that upheld segregationist policies against non-white citizens of South Africa.

That’s how you explain it, wrapped all neatly in a bow, but it was horror. It was devastation. It is a wound that is still healing for this country—24 years later.

I’m a white citizen, and I was nine years old when the freedom of democracy was introduced to South Africa.

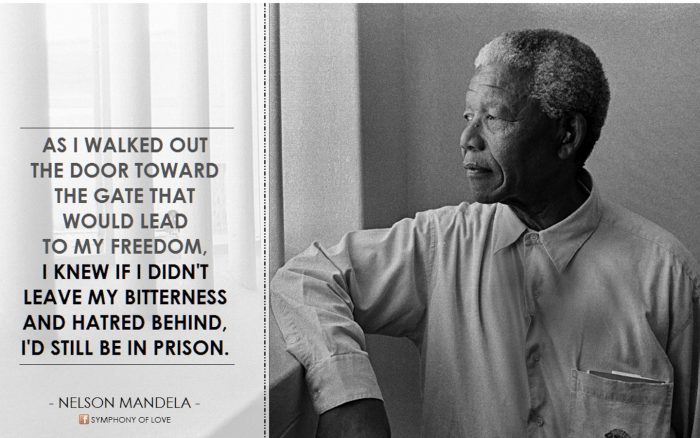

I remember when Nelson Mandela was voted in and made his iconic speech at City Hall:

“Friends, comrades, and fellow South Africans, I greet you all in the name of peace, democracy, and freedom for all. I stand before you not as a prophet but as a humble servant of you, the people. Your tireless and heroic sacrifices have made it possible for me to be here today.”

I wish I could say that I was old enough to comprehend the magnitude of what had just transpired in my homeland, but alas, I was too young to understand. I’d had little interaction with “non-white” people until the great change—the great freedom.

A great freedom so many struggling leaders fought for, hard-won. A freedom for people who had suffered in ways I still can’t fathom.

Men and women stood for over eight hours, queuing to cast their vote for the first time—ever. Some at the age of 63, having lived almost their entire lives under tyrannical rule. Eight hours compared to 27 years on a small, desolate island? It was chump change in comparison and worth every second for them. So they stood, and they stood, and they stood until they could mark that ballot.

My father was a staunch Afrikaans man. He passed away when he was 37; he was a driving-drunk kind of man. The culmination of his life was a car veering off the road and rolling down a hill after years of self-abuse, having never recovered from his conditioning.

He was a raging racist—the worst kind.

He considered Black people to be less than himself, and there were times, after freedom, that he would use words I will absolutely never say. He held “values” that I have absolutely rejected with every fiber of my being—and always will

I want to say that he didn’t waste his life, but he did.

He was in the army and became an alcoholic after. I believe the pain was too great for him. There must have been a small part of his soul that recognized how hate and segregation is poison, and he did the only thing he knew how to do: he drowned his sorrows with a bottle.

I have often wished I could sit with my racist father and ask him the questions I have wanted to ask since the day I learned about apartheid in school. Since I discovered, researched, and delved into the details of the country’s tumultuous past—since I wept for the sins of my father.

I was fortunate enough to attend a talk with Christo Brand, Nelson Mandela’s prison warden, and I listened with great intent as a white, Afrikaans man recanted stories of developing a friendship with one of the world’s greatest heroes.

How two people, Black and white, on opposing sides had broken the barrier of hate and discrimination and found a love for one another. The triumph of the human spirit, connection, freedom, love, and willingness to change, reconcile, and forgive.

I struggled for a long time to try and understand why the person who had given me life, my own father, could have been so riddled with hate and play a part in a system that makes my blood run cold.

The first time I met and befriended a Black girl, I was in primary school. Her name was Gabby. She was the most beautiful little girl I had ever seen, and she was happy. She had a grin as wide as a Cheshire cat, and we quickly became best friends.

I asked my father if she could come for a playdate, and he said, “Is she white or Black?”

I was floored by the question. What did it matter, I thought?

“She’s Black, daddy,” I replied.

He laughed, but not a laugh of any real joy; it felt bitter and cynical, “She can come if she cleans the house,” he continued.

I ran from him, and I cried.

He doesn’t know Gabby, I thought. He doesn’t know she’s my best friend and I love her!

I will carry that story with me for the rest of my life.

I never asked again for a person of color to come to my house until after he died. I never wanted any of my friends to feel shamed or unwelcome for merely having a different skin color.

I don’t want this article to come off as a woe is me piece.

I know that I will never be able to truly comprehend the trauma that the old generation caused. Still, I know that as I grew older in a democratic country—as I stood in awe of all that Nelson Mandela and his comrades had done—I held their beliefs in my heart.

And I see it all now: all the sacrifices they had made, missing their children growing up, being offered their freedom if they just went back to the system, and having the greatest human strength to say no, and then being returned (immediately to their torture) at Robben Island.

I promised myself that my daughter would never grow up in a house of hate for another human being’s skin color.

She recently had a history assignment and asked me, “Mom, can you explain apartheid to me?”

I replied, “Get the laptop, bring the textbook, and let’s get some tissues. This is going to take a while.”

My father was a racist; I will never be one, and neither will any of the future generations I play a part in.

I will keep telling the stories of the heroes who started a revolution and changed our world.

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 20 comments and reply