“It’s impossible to get lost on this trek.”

This was a mantra often repeated by people I met while preparing for my first five day trek to Poon Hill—a section of the Himalayas in Nepal. I wanted to tell them not to challenge me: I have a knack for getting lost, after all.

My partner in crime for the trek was the goddess Araxeli from Spain. We became fast friends after attending a 10 day Vipassana silent meditation course together the week before. She is hilarious and full of passion for life, so we spent most of our time laughing and talking with wild hand gestures.

I packed up one extra pair of tights and a single flannel shirt. Honestly, my bag was 65 percent snacks, a ratio I would regret on our first cold mountain night. I was stubbornly bent on traveling light, even ditching my camera so I could fully soak up my first big mountain experience

It was like this that we began our trek.

Day one, hour one: I am panting. I am from flat country and in no shape for this rapid elevation. Up, up, forever up. I fear the entire trek will look like this.

A jaunty guy from Colorado breezes past me—I am not kidding—he is whistling. Everyone has their way up, I guess. He gave me a few tips, having just completed a trip to Everest base camp. Others wheezed alongside me in the early days, empathetic to my plight.

But I learned very quickly to tune everyone else out and march to my own rhythm. It seemed to be the only way to go. I sang songs, counted steps. Focused on my breath. Whatever would stop me from thinking about how much further up I still had to go.

The trail was relentlessly straight up for seven hours. We increased our altitude by 1,000 meters (3,280 ft) in the first day (which is no small feat), and another 1,000 meters on day two.

My steps become a dance in animal poop avoidance, and I was left wondering how a giant cow or yak can possibly do something this nimble when I am so exhausted and clumsy on the trail. My heart beats thickly in my chest. I eat constantly, maybe just to feel normal. I wonder how fast is too fast for a heart to beat.

We walk. Hiking is very pragmatic; logical. There is no real strategy and there is only one way up. That is to put one foot in front of the other until you reach the top. All the fancy hiking gear in the world won’t take your steps for you.

We join a group of guys from India and England who effortlessly fall into step with us for the middle days. They had me dusting off the word “gentleman” to describe them. I realize a gentle spirit might be my favorite quality in a person. We tromped through fairy tale forests and rock statue gardens like a bunch of happy kids, eating baby strawberries from mossy rocks and learning about each other along the way.

And finally, on night three, we see a glimpse of the elusive, snowy Annapurnas. We stood shoulder to shoulder and stared. I understood then why Nepalese people revere the Himalayas as gods. I understood why people spend every dime to try and summit Everest. I fully grasp the reverence with which people treat mountains. I kept thinking about a passage from The Snow Leopard, a magical book about a naturalist’s search for the big cat in the Himalayas.

“In the early light, the rock shadows on the snow are sharp; in the tension between light and dark is the power of the universe. This stillness to which all returns, this is reality, and soul and sanity have no more meaning than a gust of snow; such transience and insignificance are exalting, terrifying, all at once… Snow mountains, more than sea or sky, serve as a mirror to one’s own true being, utterly still, utterly clear, a void, an emptiness without life or sound that carries in Itself all life, all sound.”

~ Peter Matthiessen, The Snow Leopard

Matthiessen speaks my mountain truth here.

I could shout my excitement or internalize it. None of it would change the mountains. They would simply reflect the fluctuations I experienced, making me more self-aware. Unlike the sea in her wild ways, who you can count on to define impermanence, the mountains provided an opposing structure. They embodied presence. I could turn my back and feel them watching me. If I went to bed and woke up in a different mood, they would remain exactly where I’d left them the night before. Maybe hidden by a cloud, but always there.

The next morning, we drink coffee together and soak up the sunny views. It comes time to part ways with our mountain men and it is just Ara and I again.

Though we miss their sure step and lovely company, we also have to move on. Our goal is to reach the hot springs in a village called Jinu Dada. It is purported to take two hours by five different sources (we will learn much later that everything takes two hours) so we have a leisurely breakfast and slowly get moving.

Ara and I walk down mountain, talking about life. I learn that Peter Pan is a phrase also used in Spain to describe a certain kind of guy. For some reason this delights me. We laugh a lot and talk about love and other things, in the easy manner of old-new friends. The day is beautiful and we are giddy with the idea of soaking our tender muscles in a natural hot tub.

Two hours pass and we don’t arrive but we justify our slow pace because we are new to trekking. It will be hours before we look at a map.

Directions are the last thing on my mind at this point. I am overwhelmed by natural beauty.

The greenest hills I have ever seen blare against the bright blue sky and puffy clouds straight out of a cartoon. We reach a restaurant and guest house—the trail is peppered with these cozy little oases.

There, at the top of the most stunning place I’ve ever seen, two men sit unintentionally posing for the photograph of a lifetime. I snap it with my mind, in the hopes of remembering every single detail.

They are dressed in traditional Nepali hats and wear the whitest pants, somehow not stained by farm work and time. Their thin legs pointed toward each other as they lean in to the conversation. Men in this part of the world sit close, touch often. There is something tender about the way these two men listen to each other. I am so charmed by their exchange that I just observe, forgetting that I meant to ask them if we’re headed the right way.

The man on the right gives us directions in shaky English, laughing at his mistakes.The man on the left smiles and I am done for; he is so genuine and welcoming that I might have followed his directions off a cliff, though it didn’t come to that.

The elder brother gestures vaguely toward our intended path and pantomimes a gate that we will have to lift to get on our way. By the time we actually reach it, neither of us remembers how to open it. Despite all the innovations we have at our fingertips as Westerners, this simple wooden gate has managed to perplex us. The end result is to beach ourselves on the top post and flop over to the other side in a very ungraceful manner.

We walk on, not saying a single thing. Words have become like extra things to carry at this point in the trip. I am spaced out on the countryside. The two men are far behind us. No other trekker is in sight, as it is low season and they are scarce.

Our version of true north is the river—so long as it stays on our left, we are going the right way. There is something raw and powerful about such a guide. Following the roaring river makes me feel protected. Surely we can’t lose sight of that. The only other creatures who share this are a family of yaks who stare directly into the pit of my soul while they chew loudly on some grass, some ditzy goats who trip over stones and pairs of paper thin butterflies that dance between my feet as I walk.

We weave down mountain; unraveling every single stitch we’d carefully sewn up with each step of yesterday’s arduous climb.

In one second, it begins to rain. Again. There is a tiny ritual I’ve adopted when the monsoon rains come. I grab my bag cover, throw on my rain jacket and plow onward, hoping for dry socks at the end of it.

But this time, I don’t care if I get wet.

I stare up, tilt my head back and let the rain wash over my closed eyes. In that moment, I notice the giant orange and red wild roses and feel happy that they will never appear in a bouquet for someone in the U.K.; a fate of many flowers from Nepal. They will be allowed to grow free for the enjoyment of those on this mountain alone.

In that moment, I have nothing but a four pound bag, five wet pairs of underwear that I haven’t worn for the entire trip, half a liter of water and some gross fermented raisins to my name. In that moment, no one in the world knows where I am except Ara, who has continued walking and is now out of sight. As far as I am concerned, in that moment, I am alone.

In that moment, I am wild.

It’s a feeling I have never had before. The closest I’ve come was standing alone at the helm of a sailboat on the ocean while the whole crew rested down below. There, only the stars aided my journey on the water. But even then I was accompanied by the buzzing of the Coast Guard radio and the knowledge that if I needed them, my Captains were only a word away.

This had the feeling of complete solitude, total communion with mountains and self.

So often, I think we get it wrong with nature. We speak of the real world as something we resign ourselves to rejoin after the adventure is over. But I wonder what could be more real than how I feel in this moment. I try to imagine a set of responsibilities in my life that could compete with outdoor survival and come up a little short.

I let this feeling wash over me and refresh my tired steps, catching up to Ara by the jumpy suspension bridge that joins two worlds over the river. We have a chance meeting with a group of school children wearing dingy white shirts and pristine pleated uniform skirts. They bravely ask for sweets and writing pens. I am happy to oblige with the pens—finally validated in my instinct to pack eight of them but no extra warm clothes.

I muse that I am now an artistic benefactor, maybe kick-starting the next great Nepali writer with my simple gift. Then I remind myself to stop fantasizing and stay present but I’m already miles away, wondering if they’ll thank me in the intro of a revolutionary book that will one day change the fate of the world.

The kids run on, racing with sure feet over the bridge which had my knees wobbling with nerves. Every 10 feet, they pause and scream “goodbye!” over the voice of our raging river guide. We holler back “goodbye!” They do this until we are almost out of sight, pausing every few minutes, just to be sure of us. Maybe to look out for us. This is, after all, their backyard.

Now it’s easing into hour four. Usually, you just double the time someone gives you and you’re there. But the rain has picked up and we finally get the feeling that we might be lost.

My feet begin to itch. I mean, really itch. They are burning and my socks are crumbling into my sneakers. Ten minutes. Twenty. I am beginning to lose it. I mentally try to scratch my feet. No good. I try to use my meditation technique to ignore the sensation but I realize I don’t have that kind of discipline in the face of such grotesque discomfort.

I finally stop, rip off the offending garments and scratch the soles of my feet like a madwoman. Ara may be thinking “my hiking partner has lost her mind,” but she simply smiles at me and offers me her only pair of dry socks in a gesture of true friendship.

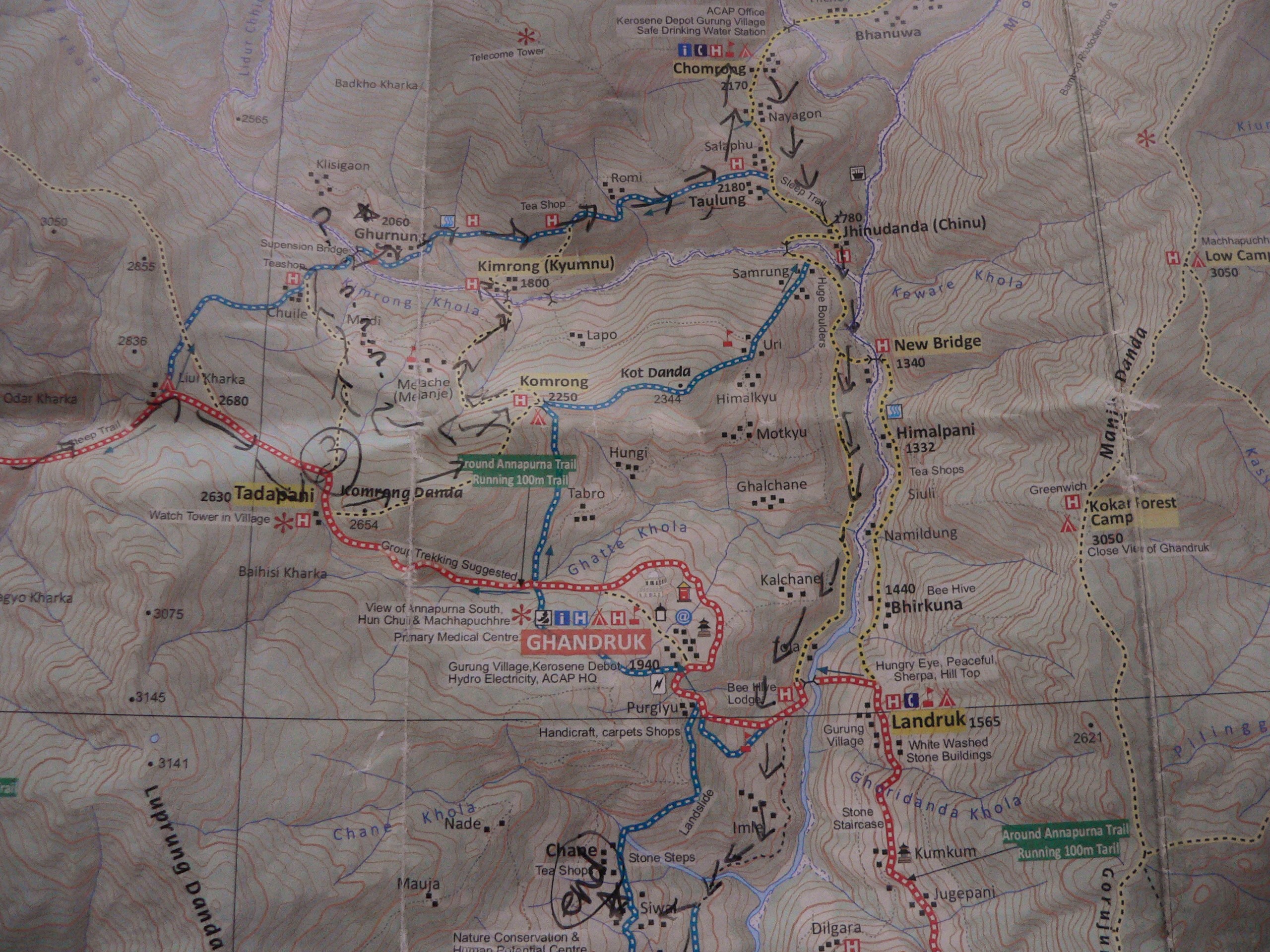

We finally stop for tea and check the map. Our waiter tells us Jinu Dada is four hours away, making this an eight-hour trip instead of the original two. Looking at our route, we had somehow managed to go off the path, find another one, walk backwards and then get on a parallel path. It is only a few hours until sunset, so this presents a whole new set of concerns. I am fully accustomed to getting lost, but this is a record even for me.

We react with disbelief, frustration and a touch of that crazy laughter you have when you don’t know what else to do.

The waiter brings my tea at the height of all these emotions. As I try to quiet my mind, I see my mug is painted with the astrological sign of Taurus. Ara informs me that she is a Taurus and we read the attributes on the mug, starting to feel our spirits lift. Then he places her mug on the table and we see it’s Leo, which is my horoscope sign. I squeal in disbelief.

“It’s a sign!”

For whatever reason, this happened. Maybe to let us know we were fine. Or that we would look out for each other. Or that we just had to accept our fate.

Four more hours in the rain. The humidity. The itchy soles of tired feet. We will just have to walk on.

One foot in front of the other. There is a moment now where we have to choose which direction. I am skeptical because we’ve been wrong so many times already. Just when I almost turn to ask Ara her opinion, I see a ridiculously blue bird perched on the branch just over the fork of the path going left. Her coloring reminds me of accidentally mixing paint colors as a kid—the outcome thrills you but it’s impossible to describe or recreate because it’s never existed until now. She is so stunning that we could not have missed her. We choose that route and the bird disappears, satisfied that we followed her instructions.

We walk and walk, not speaking much. Young Nepali guys lug baskets full of plants from straps affixed to their foreheads, which are tilted down to stare at cell phone screens. We maneuver around chicken coops and down steps built for a giant’s legs. Two huge dogs that might have been Rottweilers in another life follow us, refusing to turn back for home until we reach the mouth of the next village. We continue on, thanking our canine guides and cracking the occasional joke for the sake of morale.

In the village, we walk past a school and a workman pops out from a hole he must have been digging all day long. The combination of his curiosity and my surprise causes us both to burst into loud laughter. I mime to him what was on my mind- he had reminded me of a jack in the box. We laughed until I was well out of sight and closing in on another small village.

It is hour eight by now and we have less than an hour until the sun sets. I wonder if it is possible to sleep standing up.

Then I hear Ara’s soft voice from far away, “Erin!”

I scurry over, following her adoring gaze to the snowy Annapurna peaks which had veiled by a cloud until now. Resting in the bones between two mountains was a vibrant double rainbow. We collapse in giggles and dodge a whole mess of work ponies, racing up the steps with fuel containers tied to their backs.

We had made it to the next village, Chomrong. Off course, to be sure. Not Jinudada, not yet. But somewhere with beds and lots of food.

After a blissful night of sleep, the wonder woman of our guesthouse brought me a mug of coffee. I turned it around, just on a whim, to see its decoration, maybe pushing my cosmic luck a tiny bit.

Sure enough, it was painted with Leo the lion, my horoscope. I giggled and tried to explain the reason I felt so joyful but didn’t really have to.

Before leaving, we asked the couple how long it would take us to reach the hot springs.

Without missing a beat, her husband replied, “Two hours.”

The funny thing is, this time it really was.

~

~

Author: Erin Johnson

Images: Author’s Own & Amanda Sandlin/Unsplash

Editors: Caitlin Oriel; Katarina Tavčar

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply