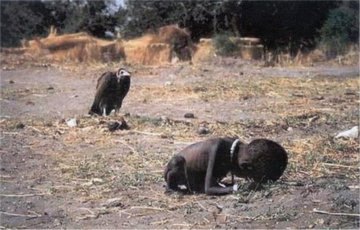

In 1993, during the height of the Sudanese famine, South African war-photographer Kevin Carter captured the iconic image of an emaciated child struggling to reach a feeding center—a vulture waits nearby. Known as the “image that made the world weep” (also Struggling Girl and Sudanese Girl), it was first published in the New York Times and quickly splashed across newspapers worldwide.

One year later, Kevin Carter won the ultimate honor in photojournalism, the Pulitzer Prize. Three months later he committed suicide.

There have been many articles and movies about Kevin Carter’s life and this image. Certainly there were other factors that may have played a part in his decision to end his life: winning the Pulitzer Prize just three months earlier—along with sudden fame; the furor over the tragic image (he was compared to being a predator, another vulture on the scene); the public outcry demanding to know why he didn’t put his camera down and help the child; and the heartbreaking death of his best friend and fellow Bang, Bang Club member Ken Oosterbroek. The culmination of these events, along with other factors led to a compounded tragedy.

In his suicide note, Kevin Carter wrote:

“I’m really, really sorry. The pain of life overrides the joy to the point that joy does not exist…I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings and corpses and anger and pain…of starving or wounded children, of trigger-happy madmen, often police, of killer executioners…I have gone to join Ken if I am that lucky.”

Struggling Girl, Kevin Carter/CORBIS/Sygma

The New York Times was overwhelmed with readers demanding to know what had happened to the child.

Kevin Carter had said both that he took the photo because it was his “job title,” and left (the child there)—in other accounts he stated that he waited for 20 minutes or shooed the vulture away (the child made it to the feeding center). There were also accounts of UN workers in the area telling him not to touch anyone because of the possible spread of disease. In all accounts, it’s easy to be an arm-chair quarterback and declare what he should have done differently. For me, he did his job—he took a photo that brought the needed attention to the tragic famine.

My empathic nature makes me want to believe that he did chase away the vulture and the child did make it to the feeding center and survived. I cannot say what I would do in this situation, I can only have hope. Hope that I would have the foresight, courage and loving kindness to do both: take the photo and help the child. The photo was important. One could say that it was a catalyst in securing foreign aid for the famine, saving millions of lives.

Sadly, today, with our need to see tragic images in order to act and react, images like Struggling Girl are important messengers of what is really happening. One only need to recall last year’s heart wrenching image of the three-year-old lifeless body of Aylan Kurdi washed up on the Turkish shore. That single image provided a positive and sympathetic, yet short-lived response to the millions of refugees fleeing war-torn Syria. The need to connect visually to these tragedies has become the norm. There is an expectation for anyone with a camera to be where there’s a tragedy and to “shoot first, think later” (photographically-speaking). Images are uploaded live and our cameras are in the face of the shocked mother at the very time she’s hearing that her son has just died.

When will we reach a saturation point—or did we already go too far? There’s the term “Compassion Fatigue,” where we become numb to seeing shocking images too much. I think the opposite has been true—we have become an insatiable beast, like extras in a zombie film, hungry for more shocking images and reality TV-style “horror as it happens” brains!

This tragic story has haunted me personally throughout my career as a photographer. I vividly remember feeling a connection to Kevin Carter’s life, a deep-seated uneasiness about that photograph (and other images of his). I couldn’t understand what this feeling was at the time, so I let my default setting shove it deep down and bury it inside. Still, year after year, there was a soft voice whispering to me, “Don’t choose that path. Don’t be a photojournalist. Don’t get too close. You won’t survive. Your fate will be the same as his.” Now, decades later I understand why. I was not ready then, not strong enough. I had no emotional safety net, no healing tools in my therapy tool belt—no way to catch myself if I fall. But I’ve always felt that pull, my empath and Aquarius centers converging to save the world yet I didn’t know how.

There are no easy solutions to most of the problems in today’s world, this visual hunger included.

Many photojournalists have sourced Greg Bryant’s 4-point checklist for ethical photography. With images such as Struggling Girl, we can use this checklist to come to an understanding of the ethical decision making process—not what Kevin Carter was thinking. He is not here to speak for himself. But what we might ask ourselves, as citizens of the world walking around with our smartphones and cameras.

Gary Bryant’s Checklist:

Should this moment be made public?

Will being photographed send the subject into further trauma?

Am I at the least obtrusive distance possible?

Am I acting with compassion and sensitivity?

Perhaps we can use some lessons from this terrible event to move forward, to apply some of these checklists to our Facebook-and-Instagram-saturated world today. To consider what we’re ingesting visually on a daily basis and how much of that is necessary or beneficial to living a mindful life. The comment sections online are rife with blame, shame and hate. In 1993, the public could only call or write in to express their anger and condemnation for Kevin Carter’s image. Today, that image would be viral in minutes and everyone would have an opinion. We know what that would look like, we’ve seen it too many times already.

But if violence begets violence and hate begets hate…then surely loving kindness must beget loving kindness. It has to be said that these images, Struggling Girl and that of Aylan Kurdi must have some role in society. They are real images of real people. No sugar-coating, no editing—they speak for themselves. These images are necessary, they bring attention to the wrongs in the world. But it feels as if the balance shifted a long time ago and we can no longer trust what we’re subjected to visually even when scrolling through our newsfeeds.

My default setting is to shield myself from those images, to hide away. That also cannot be the right answer, or a practical solution. This image from Kevin Carter has stayed with me for two decades…I’ve been carrying around the weight of that image and his suicide, what it means to me as an artist and as a reminder to protect my soul from his same end result…to play safe. Researching this event again was a wake-up call for me, a not-so-gentle reminder that I was supposed to do something about this. I was supposed to be stronger, to use my voice to help others—to make a difference. I’m now on the path to discover that voice and maybe that’s why this image came bursting into my mind when we were given the assignment. This time the voice wasn’t a warning, it was saying “Okay, now.”

The mindful way is to find the good in the bad…to learn something from every situation. Perhaps from the tragic case of Kevin Carter, we can use the ethics checklist when we’re taking or viewing images. At least to start with the first point “should this moment be made public?” and work from there.

It’s not the solution, I’m not sure that exists. But it’s a start…and loving kindness begets loving kindness. It does.

Author: Julie Balsiger

Image: Public Domain Pictures

Editors: Emily Bartran; Catherine Monkman

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 8 comments and reply