If I had to thank our current social and political climates for one thing, it would be for thrusting the word “privilege” into the pop culture spotlight.

It frequents conversations among millennials as well as some Gen Xers, and younger generations are growing up while the conversation develops. That said, privilege has proven to be a hard pill to swallow across generational lines.

For some, it’s hard to digest just how privilege has worked in their favor throughout their lives—namely because they never realized it existed in the first place. That’s how privilege works: for those of us who have it, we don’t usually realize it until we have an “aha” moment, which often entails someone explaining it to us; but for those of us who lose out as a result of lacking privilege, the awareness is a part of our most basic conditioning.

For that reason, not being aware of privilege is a privilege in and of itself.

But even among my fellow liberal, ever aware, listening-to-all-the-podcasts millennials here in New York City, where I hear the subject tossed around regularly, I’m not sure we always understand the complexity of what we’re discussing.

Yes, we acknowledge that privilege is real, that some of us are afforded more opportunities simply because of our gender or the color of our skin. Yes, we talk about the fact that this often works out poorly for those who lack privilege in certain aspects.

And it’s great that we talk about these things. It means we’re growing in our awareness, and no problem ever gets solved without our first becoming aware of it.

But—and it’s a big but—what’s often missing from the conversation are two components:

The first is a real way to change the systematic imbalances of privilege, and the second is any sense of responsibility in doing so.

We can’t address either of these things without first acknowledging the complex nature of intersectionality, which is another break in the chain of communication, even among those of us who consider ourselves informed on this ever-growing conversation.

Privilege is not one-dimensional, but rather intersectional.

This means that multiple factors can contribute to a person’s privilege or lack thereof. I find it’s easiest to see this by looking at various pillars of institutionalization, or any number of factors that shape us in establishing ourselves in society.

Sure, privilege can be about gender or race, but if we consider where these two factors intersect, we can say for example that yes, white women with equal qualifications make less money than white men for the same work, but black women make even less.

If we then consider where gender intersects with geographical location, we see a different facet of the same issue; according to a Forbes write-up on the geography of the gender pay gap in 2013, Nevada and Vermont both had the highest ranking (let’s call it the “least awful”) pay equality, with women making 85 cents for every dollar a white man made.

On the flip side, women in states like Wyoming, Louisiana, West Virginia, and Utah made somewhere between 64 and 70 cents on the dollar.

Now let’s factor race back into the equation, adding it to the gender-geographical dynamic. This intersect means that while a Latina in California might make closer to 80 cents on the dollar, that same woman might only make 67 cents on the dollar if she’s in Alabama. (These are hypothetical numbers, but it is a fact that Latinas are the lowest paid workers in the country.)

And then, in that same context, we have to consider education. What’s accessible to a person of whatever racial background, whatever gender, in whatever part of the country they’re from? What’s the likelihood that they will have the means to pursue an education? What’s the likelihood that they’ll even think they can or should?

This calls into play a full platter of other influences: in addition to race, gender, geography, and education, we also have religious, familial, and socioeconomic influences, to name a few. There’s also the all too frequently missed factor of being differently abled, be it physically or mentally. Sexual orientation is a big one, too. We could go on and on, but the point is that privilege is intersectional, and so we all have or lack varying degrees of privilege based on all these factors at any given crossing point.

Now here’s the fun part: we don’t often talk about how we can address major imbalances in privilege, and I think that has a lot to do with wanting to avoid the responsibility of changing it.

It’s easy for us to look at well-known filmmakers and say “they should cast more minorities in their movies,” or to point to celebrity musical artists and ask, “Why don’t they give more of their money to organizations supporting women leaders?”—because that removes us from the solution and puts it on someone else. Someone who seems more powerful, more capable of contributing to change in a big way.

And while these people may have greater name recognition, more money, and more resources for changing the playing field—which is absolutely useful and makes big difference—leveraging privilege is not just a job for those in the public eye.

It’s on us, too.

And while we may not have fame to help us do it, we can certainly address and leverage our privilege in a way that still makes an impact, and this starts with acknowledging what privileges we have.

To acknowledge privilege is to realize that I may have worked my tail off to achieve whatever I’ve achieved, but that someone else who worked just as hard, maybe even harder, wasn’t so fortunate—and may never be.

It’s to understand that I’ve never had a scary interaction with a police officer because I obey the laws, but that others who also obey the laws may very well be shot and killed—because they’re black.

It’s to recognize that I grew up with parents who told me I could do anything, in a town where I was surrounded women who got degrees and made careers for themselves whether they chose to be wives and mothers or not, but that girls in other places may not even know what they want for themselves because they only know what’s expected of them.

Yes, I’m still a woman, and my last name is still Rodriguez, and so there are certainly privileges I don’t have quite like a white guy from the Upper East Side named John Smith might; however, it’s not lost on me that I am, in fact, more privileged than others who look like me on paper.

So for those of us already having this conversation, we need to accept what privileges we have. No shame, just acceptance—not only of what our privileges entail, but of what this implies as far as our responsibilities in changing the playing field are concerned.

Because as people with any degree of privilege, the ball has always been in our court to do the right thing, and the right thing is to invite and amplify underrepresented voices in the conversation.

If we have the luxury of feeling safe in our environment, it’s our responsibility to speak up and look out for those who are unjustly robbed of that sense of safety.

If we have access to educational opportunities that put us ahead in our field, it’s our responsibility to seek out and connect with those who may not know those opportunities even exist—to open a door, to create some kind of means to a path they wouldn’t otherwise see as a viable option.

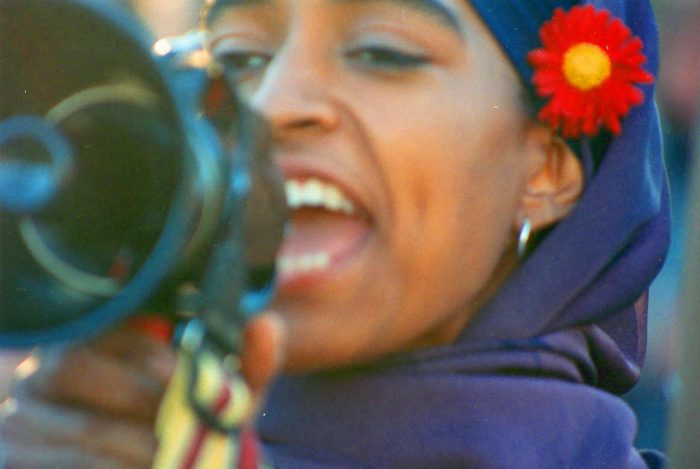

If we have a platform of any kind, it’s our responsibility to use it not only to give others a chance to stand up and speak—without interruption or insult—but to first and foremost inspire them to contemplate having something to say at all, to make them believe that they, too, are worthy of being heard.

If we have a seat at the table, it’s our responsibility to pull up a chair for those who wouldn’t otherwise get one—and to consistently offer mentorship and support if/when they doubt their worthiness or feel out of place.

If we have even the slightest hope for a more equal future, it’s our responsibility to take advantage of every chance to pay it forward, in the most effective way, in any given moment.

It’s not a “free handout,” which is how you’ll hear it explained by those who aren’t quite there yet in terms of understanding and accepting privilege as a fact of life. It’s an active choice to cultivate an even playing field. To strive for equality. To make the future brighter than the present.

It’s the right choice to make. And I hope you make it.

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply