We’re in the midst of celebrating the 50th anniversary of the event that came to define the 1960s counterculture, the Woodstock Festival.

Watch for aging hippies waxing nostalgic about those three magical days, whether they were there or not, and for endless commentary on the historical, sociological, and cultural meaning of the festival. For my part, I want to commemorate one brief but highly significant moment that occurred in the opening hour, on August 15, 1969. It does not get the attention it deserves.

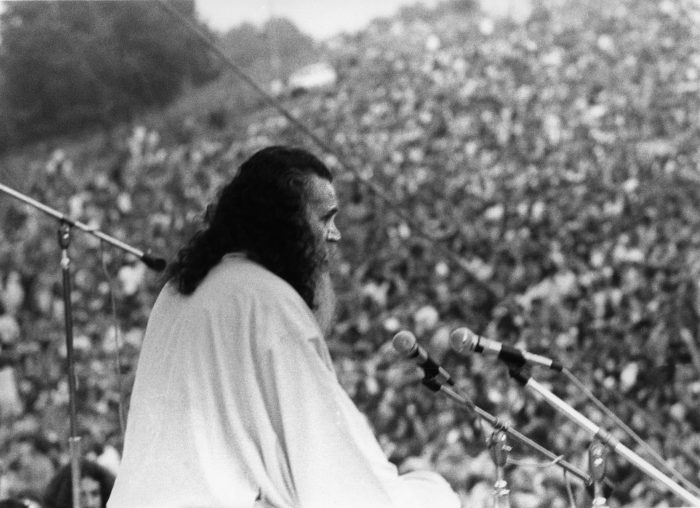

Of all the iconic Woodstock images—writhing mud-soaked bodies; impassioned performers like Jimi Hendrix; ecstatic faces and strung-out faces—one captures the spiritual zeitgeist of the era: Swami Satchidananda addressing the multitude. It’s a potent symbol of the meeting of East and West that transformed America’s spiritual and cultural landscape. Fifty years on, millions of people meditate, chant mantras, and stretch on yoga mats, and the swami who came to be called “The Woodstock Guru” deserves much of the credit.

Swami Satchidananda was born C.K. Ramaswamy Gounder on December 22, 1914. A family man with a successful business in South India, he became a wandering ascetic after he lost his wife at a young age. Several years later, in 1949, he arrived in the holy city of Rishikesh, where he met his guru, the legendary Swami Sivananda, who trained two of the seminal figures in Western Yoga: Swami Vishnudevananda, who came to America in 1957, and Satchidananda who came nine years later.

In 1966, while teaching in Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon), Satchidananda met an American filmmaker named Conrad Rooks, who flew the yoga master to Paris, where he was filming a movie called “Chappaqua.” Satchidananda appeared in the rarely-seen film, which also featured the work of two then-unknown artists: composer Philip Glass and painter Peter Max. Max, whose flower-bedecked posters would become the visual backdrop of the hippie era, invited the swami to New York.

It was supposed to be a brief visit, but Max’s hipster friends liked having the guru around, so Satchidananda started teaching in a rented apartment on West End Avenue. He called it the Integral Yoga Institute (IYI), and defined his system as “the complete Yoga, which integrates all aspects of life and maintains our natural condition of an easeful body, peaceful mind, and useful life.” His popularity grew quickly, and by January 1969, he was speaking to a packed Carnegie Hall.

Seven months later, some of his resourceful students drove him north to Woodstock, when, at the last minute, the festival organizers reached out for help in setting a peaceful vibration. They got stuck in the monumental traffic jam and flew in a helicopter the rest of the way. A casting director could not have found a better person to fill the role of a wise elder calming and blessing 400,000 restless young people.

Tall, handsome, and stately, with long black hair and a graying beard, he sat cross-legged on an elevated platform, wrapped in orange, and gently delivered a benediction that resonated with the baby boomers’ sense of importance. “America is helping everybody in the material field,” he said, “but the time has come for America to help the whole world with spirituality also.”

Fully aware of the volatility of the era (Vietnam was raging, Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy were assassinated a year earlier, inner cities were powder kegs), he told the crowd that to establish peace we must “find peace within ourselves first.” Then he offered a taste of exactly that, following his short speech (you can read it in its entirety here) with a traditional Sanskrit chant and a short period of silence. Excerpts of his talk were viewed by millions in “Woodstock,” which won the Academy Award for best documentary.

To this day, many believe that the good vibes generated by Satchidananda averted what might have become a catastrophe when the rains came, and contaminated drugs circulated, and food and shelter became scarce. That may or may not be so. But it is certainly true that his presence reinforced the growing awareness that India had something of value to offer the West.

The image of the Hindu holy man blessing the most famous rock festival in history will endure as a symbol of the time when a generation of Americans turned Eastward and inward.

In the wake of Woodstock, Integral Yoga International outgrew its West Side apartment and purchased a building in Greenwich Village. It remains a New York fixture. In the 70s, 80s, and 90s, Satchidananda logged nearly two million miles traveling the globe sharing the message of Integral Yoga. Today, a thousand-acre property in central Virginia that he established continues to thrive as Satchidananda Ashram—Yogaville, headquarters of Integral Yoga International. He passed in 2002.

No one contributed more to the modern yoga boom than Swami Satchidananda, who started training American teachers in the early 1970s. His legacy is also evident in the growing acceptance of yoga in the mainstream medical community. Two of his early followers, Doctors Sandra McLanahan and Dean Ornish, led the way in legitimizing the use of yogic practices in healthcare—and, through them, to Dr. Oz’s advocacy on TV.

For his many contributions to the trend lines that turned America into a nation of yogis, Swami Satchidananda deserves to be celebrated on this Woodstock anniversary, along with the musical icons who performed and the hardy pilgrims who attended—and even the aging boomers who weren’t there but tell their grandkids they were.

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 2 comments and reply