Pandas agree that bamboo is the top and no horse rejects grass, hay or apples. These same foods are the staples that nurture exactly the animals who have turned to liking them. The human animal of this day, however, and contrarily to most other animal species, cannot agree on what to eat and drink.

Not from an ethical standpoint, and neither from a health perspective.

There simply seems to be no sealed agreement as to what the proper human diet is, and not even as to what foods are healthy, at least if browsing through the internet with an open mind.

Maybe we are too brain-fogged, sugar-rushed and caffeinated to think clearly, and probably we have processed and adapted foods so extensively that our taste buds have started to like things that we were never supposed to like if asking nature.

But even if we haven’t yet found the optimal human diet, there must be one.

Dining with Charles Darwin (and Jonathan Silvertown)

I’ve had a slight obsession with Darwin’s thinking for a while (read: for years!). Part of what amazes me is how we members of the human species generally like to consider ourselves very fit for life on planet Earth in a Darwinian sense of the word fit, and how we like to justify acting control over other species as if we are the most important ones living here.

If you’re curious to dig deeper into exactly that, you can read more in my semi-fictional piece of writing: “The Echo from Darwin’s Grave: An unsentimentalised piece of vegan propaganda“.

Darwin was first and foremost writing on the topic of “survival of the fittest” from a biological viewpoint. But in this day and age, biology is not necessarily the primary driver of our diets. Quite contrarily. We are surely not eating how we should be eating (just look at statistics for lifestyle-related diseases).

My interest in both diet and Darwin’s thoughts and writings has led me to have a full conversation with Charles’ great great grandson, Chris Darwin, about which diet the human race should adhere to (both in the opinion of Charles Darwin and in the opinion of Chris Darwin).

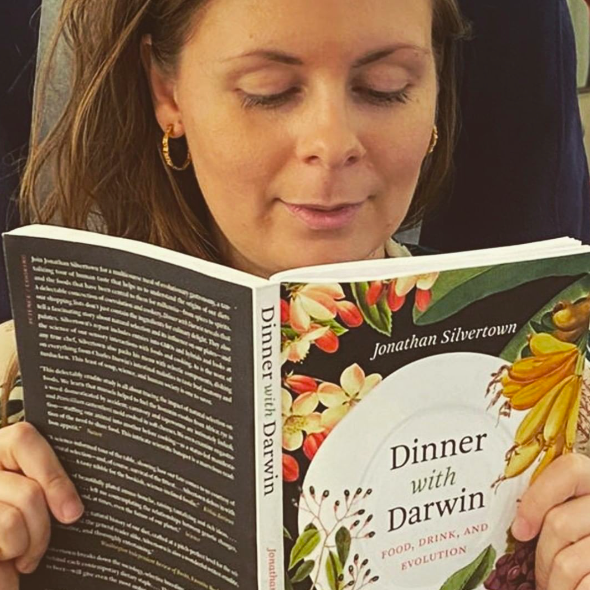

And even more recently, I’ve spent part of my summer holidays physically at a swimming pool but mentally dining with Darwin through Jonathan Silvertown’s words in his book: Dinner with Darwin: Food, Drink, and Evolution. Having set up pretty strict (however balanced) guidelines for myself on what to eat (vegan, gluten-free, low on sugar, low on processed foods, low on alcohol, and I could go on), I was curious to see what evolution had on the plate for me, and what evolution tells us about a potential optimal human diet.

Omnivore today, plant-eater tomorrow?

Silvertown presents his book as “a dinner of the mind”, and I was beyond curious to find out which answers evolution has to what I should be putting on my plate.

So what did I learn?

Right now, in the 21st century, the human species consists of omnivores, who should mainly be eating plants. Silvertown agrees with the health advice of Michael Pollan:

- “Eat food, mainly plants, and not too much.”

Further, Silvertown suggests:

- “Never eat anything bigger than your head.”

So far, so good (let’s just hope watermelon doesn’t count).

“Our meat-eating is older than the human species, or even than the genus Homo” (Silvertown), and over time we’ve grown to tolerate eating meat. But we are definitely no near carnivores: “Meat consumed to excess becomes toxic [for humans] because the surplus amino acids produced when protein is digested overload the capacity of the liver to remove them. The liver turns excess amino acids into urea, which is then removed from the bloodstream by the kidneys, but the kidneys can also become overloaded by excess urea” (Silvertown). This is because our early ancestors, despite feasting on some amount of animal flesh, were largely vegetarian.

But what we should be eating today is not necessarily the same as what we should be eating in the future. Our biology is a snapshot, not a constant.

Being in the midst of our own evolutionary process, our current biology is the result of decisions made by our ancestors, and the biology of future humans will be shaped by our decisions.

We have interfered with natural selection through artificial selection for more than 6,000 years – today’s corn breeds are the direct result of this. Since we have always aimed at picking the breeds with the best survival capabilities (this goes for everything, not for corn specifically), the process of artificial selection is analogous to that of natural selection – and Darwin was the person who realized this.

Our ancestors took one for the team making it possible for many of us today to enjoy bread, pasta and pastry containing gluten. Farmers and communities in the Fertile Crescent at some point changed to a cereal-based diet despite this being unhealthy for them. This choice is a good example of artificial selection (human choice). Natural selection came to the rescue and provided descendants of these first grain-eaters with a better enzyme mix in our saliva, making it easier for us to tolerate (and enjoy) our food.

As Chris Darwin (great great grandson of Charles Darwin) and I talked about, the vegan diet is the kinder diet to the planet and to the other species we inhabit the planet alongside.

So a burning question while dining with Charles Darwin and Jonathan Silvertown was: Could the vegan diet also be our healthiest diet? Silvertown is not convinced of this for 21st century humans. But given that we are shaping our own biology of tomorrow, it should be possible – by giving it time – to move ourselves away from the herbivore-curious omnivore and closer to the purely herbivorian domain.

It’s hard to say if Silvertown is right, and if we humans are not yet adapted to a purely vegan diet. Many others in this day and age believe that we are – so after dining with both several generations of Darwin, and Jonathan Silvertown, the conclusion remains: We humans simply do not yet agree on what our own optimal diet looks like.

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 3 comments and reply