“Again!” my daughter begs.

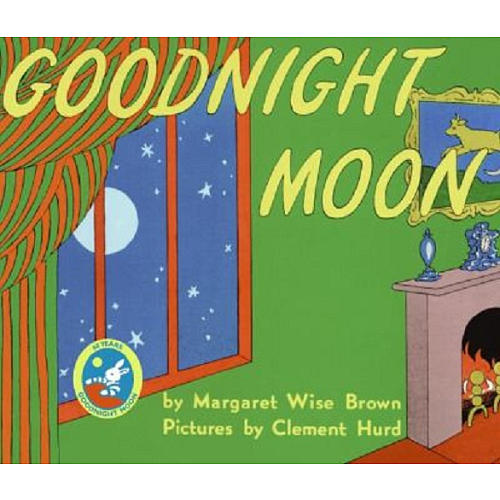

We have read Goodnight, Moon three times already and she still isn’t sated. At two-and-a-half, I’m sure she loves the repetition, and the way I pause after, “And a quiet old lady who was whispering…” to let her say, “Hush!” Like my son, my daughter loves this unique book with the illustrations that flutter from black and white to muted, primary colors.

I loved Aimee Bender’s article on what writers can learn from Margaret Wise Brown’s storytelling. Bender cites the book’s pacing, which starts off slowly in a brightly lit room, builds up to the mysterious, whispering old lady, breaks the rules by bursting the reader through the window of the room we’ve inventoried and out into the cool night air before the somewhat unexpected, unpunctuated ending in a dark room with a bunny who may or may not be asleep yet.

Bender also muses the ambiguous ending of the story, which I always find myself reciting in a whisper bordering on reverence: “Goodnight noises everywhere.” I appreciate her conclusion that Brown’s unexpected ending was likely an ending that just felt right to Brown. Endings are arguably the most important part of a story, as that is what the reader is left to steep in—a mediocre beginning, if weathered, can be forgiven in the light of a strong finish.

I agree with Bender that as writers, or any type of artist, we can learn something from this unusual, unpunctuated book. The illustrations brim with subtle movement—a roving mouse, a steady but roaring fire, a dimming lamp, and the old rabbit lady who appears and vanishes without notice.

Speaking of endings, it could be argued that the book is about death. When my grandfather died last fall, I was reading this book out loud to my daughter when the reality of his death first struck me. All those goodnights felt more like goodbyes. The sudden exit from the warm green room to the white and grey starscape, where we so often raise our grieving faces, looking for answers in the un-solid.

Then there’s the old lady, hushing and disappearing, like a ghost. The red balloon, which also retreats to parts unknown and unseen. The ending, that feels more like a falling off than the end of a bedtime story. Though the story seems to take place in mere moments, impermanence and change burrow throughout.

Or perhaps it was because I, like Bender, have more than one copy of the book—and one of them is my own hardback copy from when I was a child. Maybe it was the repetition not just of the words at the moment I was reading them, but of the memory of the child-me that was no longer a child, and the parents who once read it to me who were now the elder generation.

Even my son noted a melancholy tone about the book. “Why is the bunny sad?” he once asked.

“I think maybe he’s sleepy, not sad,” I said, pursing my lips. The bunny does look sad, but I wanted my son to sleep rather than philosophize.

I am not alone in feeling the undertones of mortality—when I Googled “Is Goodnight Moon about,” Google filled in “death.” And each time I turn that last page of “Goodnight noises everywhere” to come upon Margaret Wise Brown’s biography, my eyes always land on the dates telling me she died at the young age of 42.

But there is something else, too. This is a story about noticing. About taking inventory of what is around us, the people and objects that make up the landscape of our lives, that are so common they often become invisible. It feels like a meditation, the repetition and awareness of creatures and clocks, mush and socks. We are told to even notice the air, which is always here, so easily taken for granted. The air that becomes our breath, that breath we are taught to return to over and over again when we meditate. There is the flickering fire, the slow darkening of the room, the attention—and even a salutation—to sound.

That this book is so enduring, and that it can be interpreted in many different ways, is a testament to Brown’s talent. To do so skillfully, uniquely, and in a quiet handful of pages is something all writers might strive for.

Tonight, I will leave the book out in plain sight. Perhaps even slightly open, an invitation for my daughter. She will probably ask me to read it over and over, just as I begged my parents to read it over and over to me nearly four decades ago. I will pay close attention to the simple, abiding words, to the dimming and the pauses, to the gently jarring ending. To the air in the book and the air I breathe in. To the words that remain the same while everything else, in and out of the book, changes. And then we will start again.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editor: Travis May

Photo: Book cover

Read 0 comments and reply