When I started Yoga teacher training, I expected to dive deep into the esoteric, to bask in a rich and challenging spiritual experience, and to come away knowing how to facilitate that experience in others.

But mostly we talked about asana.

Yes, there were workshops on pranayama, the Yoga Sutras and meditation, but about 80 percent of our time was dedicated to postures.

During practice teaching, when we taught each other under supervision, I heard advice that outright contradicted my reasons for wanting to teach Yoga in the first place. Here’s what we were told:

Don’t talk about the chakras. Most people don’t care about subtle anatomy or they think that it’s looney.

Don’t use a lot of Sanskrit, especially when teaching older people. It scares them away.

The most important thing is not to make people uncomfortable, because we want to keep them coming back.

Wait. What?

I get that we want to make Yoga accessible. I can see how bombarding beginners with long Sanskrit passages, mula bandha adjustments, and partner work on vajroli mudra might be a little off putting.

But just how watered down are we talking?

If we take out the energy body and the ideas best described using their Sanskrit terms, what is left of Yoga philosophy? What is left of the spiritual path?

It turns out, what is left appears to be mindfulness—being present with body, breath and thoughts. And that’s stellar, important, not to be sneezed at. But it may represent just a wee bit limited view of the Yoga tradition.

Recently, I was introduced to the term “McMindfulness” and pieces of what’s happening in the Yoga world, at least in my Yoga world, started falling into place. I first read the term in a post over at dharmapunxnyc.com titled, “Mindfulness is Not Enough.” Then I found the 2011 essay “McMindfulness and Frozen Yoga,” from Miles Neale.

McMindfulness, as I understand it, refers to the practice of stripping down Eastern enlightenment traditions until all that is left is observing and accepting our present state, and to marketing mindfulness as a commodity.

Mindfulness, the ability to be present with what is (and whatever is), has somehow become the goal rather than one of the first steps on the path.

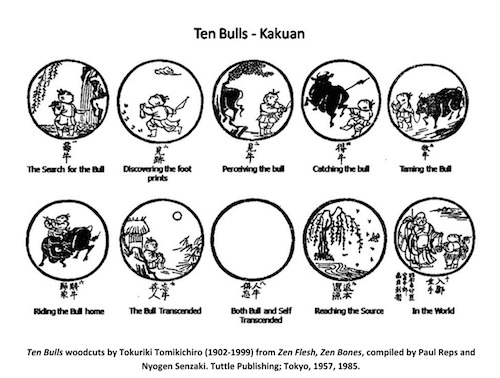

Different traditions used varying categories and terminology to describe spiritual growth. One of my favorites is the Ten Bulls or Ten Ox-herding Pictures from 12th century Zen Master Kakuan Shian, in which the bull represents the true Self.

It’s pretty clear that mindfulness is covered in the first two or three steps.

Another elegant description of the path was put forward by Georg Feuerstein as the culmination of a lifetime of studying enlightenment traditions.

According to Feuerstein, these are the seven stages of psycho-spiritual growth: self-observation, self-acceptance, self-understanding, self-discipline, self-actualization, self-transcendence, and self-transformation. Again, mindfulness is covered early on under self-observation and self-acceptance.

If there is so much more of the path to travel, why are we stuck at the beginning?

Maybe it’s because, as a culture, we are so conditioned to be outwardly focused, to speed things up and to keep distracted.

Maybe it has to do in part with our consumerism-based economy, in which marketers program us from childhood to believe that the superficial is of fundamental importance, that what others think about us is our measure of worth.

We learn not to observe ourselves but to watch others to see what they think. We don’t learn to accept ourselves; we seek acceptance from others. Everything our culture teaches us turns us outward. For many, turning inward toward self-observation, acceptance, and understanding, toward perceiving the true Self, demands a radical overhaul of our way of being in the world. That is some seriously hard work.

If this is a valid argument, then the initial focus on mindfulness may be justified. And teachers who rein in the scope of various practices are doing what needs to be done for their students.

If their students then go out and teach what they learned, they will naturally pass on this narrower message. Regardless of how mindfulness became the goal instead of one of many means toward a much bigger end, the real question is what do we do now?

If we are going to get passed perceiving the bull (pun intended), we need to get comfortable with discomfort, our own and that which we may create in others.

For me, the most important thing is not keeping people comfortable to keep them coming back. It is to teach the Yoga that saved my life when I was teetering on the edge of despair in every waking moment. I’m not going to help anyone heal and grow by hiding the discomfort Yoga can cause.

Feuerstein defined tapas as “creative frustration.” That is exactly what provokes growth. That is the discipline of Yoga.

In practice, this is difficult. I’ve been teaching for a few years now, and I still struggle with teaching for insight in two ways. The first has to do with slowing down. I often find myself thinking “Oh no, I’ve held this pose too long; they’re getting twitchy.” I think I should go faster and cover more different and difficult poses, because that is what people want.

The other struggle is with introducing Yogic concepts or reading passages because I don’t want to offend people from various religious traditions.

There are times when I give in to what I think it is students want or expect or don’t want to hear. But just as often, and more so as I become more comfortable with my discomfort, I take a breath and then the hard road. Long holds and silence, leaving people alone with themselves is good Yoga.

It’s good for students to have to come out of a pose on their own. It creates a new possibility for acceptance. It’s good for students to have to move slower than they are used to; it creates the opportunity to consider why slowing down is so difficult.

And if they don’t want to hear about Yoga, maybe they shouldn’t come to Yoga. (Gasp!)

If I relied on Yoga for my main source of income, I might be far more concerned about making people happy and comfortable so they would keep coming back.

Maybe, and I say this hoping to start a discussion, Yoga isn’t meant to be monetized and mindfulness isn’t meant to be marketed.

If the goal is to keep the majority of people coming back, can we still teach to provoke insight? The spiritual path has never been heavily populated, never been mainstream. Is this why so much of what falls under the name of Yoga now is glorified aerobics and calisthenics? Because we are trying to make it mainstream?

I am aware of modern Yoga’s derivation from the turn of the last century’s physical culture movement with its gymnastics and boxing exercises, mixed with pieces taken from the medieval Hatha Yoga texts and Patanjali minus his dualism.

But just because what came to us was an amalgamation, does that mean it’s ok to strip it further down, to throw out the last remnants of psycho-spiritual growth attached to it?

There are many, many teachers who are true to the Yoga tradition. But there are also many, many teachers who teach a different Yoga than what they believe in, the way I was taught to.

I do not teach to keep students coming back, although I love when they do.

I teach so that I might share this current adaptation of Yoga with the people who need it, discomfort and all.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editor: Emily Bartran

Photo: Flickr

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 6 comments and reply