Perfectionism is the voice of the oppressor. ~ Anne Lamott

I am a Virgo. It is my astrological nature to thrive on organization and detail. Sometimes to distraction.

You could say I am a born perfectionist. I am punctual and responsible. I love everything in its place, nice and tidy. I cannot leave a bed unmade for more than five minutes after waking (even in a hotel). If there are dishes drying in the rack, the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end; I am compelled to grab a rag and get to work.

But there is also a nurture aspect to my perfectionist nature. I was raised by two English teachers. As children, my sisters and I conjugated verbs at the dinner table. It was considered a wildly fun family game.

When I was 21, I worked in Manhattan as the executive assistant to a very French and very uptight vice president of a very prestigious corporation. Perfectionism was in the job description, and errors were punishable by disdainful silent treatment—or outright dismissal. (My boss once stood over my shoulder as I sealed an envelope for her and, with complete sincerity, reminded me to lick the stamp before I applied it.)

For 10 years, I worked as a freelance editor and proofreader for books, magazines, newspapers and websites. It was my job to make others look good. I excelled at it.

And yet, I often found myself unable to apply the same perfectionistic talents to my own life. I felt as though I was constantly making major, catastrophic, irredeemable errors!

I would lose sleep if—despite several proofreading passes—I discovered a typo in a query letter I’d just emailed to a publisher. My kitchen counters never had a crumb on them, but I always felt like I lived in a hovel. Although my clothing was arranged neatly by color in the closet, I was dissatisfied with the shabby quality of much of my wardrobe.

In short, I was Stockholm Syndromed by perfectionism.

I was so trained to do everything correctly—devouring the positive reinforcement I received when I succeeded—that not doing so was simply not an option. If something got screwed up at my hands, it wasn’t the situation that was wrong, it was I who was wrong. My very being was defective. I was addicted to approval from others, and it was slowly smothering my sense of self.

It wasn’t until I was in my 30s that I realized how exhausting it was to keep up all the organizing, arranging, filing, scrubbing, folding, pressing, stacking and tucking. Not only that, I found I spent more time berating myself for having failed than encouraging myself to keep going. I gave myself more negative self-talk than the gentleness and love I gave to everyone else around me.

Didn’t I deserve some of that love as well?

Or a better question: Why did I deem others around me more worthy of care and love than I did myself?

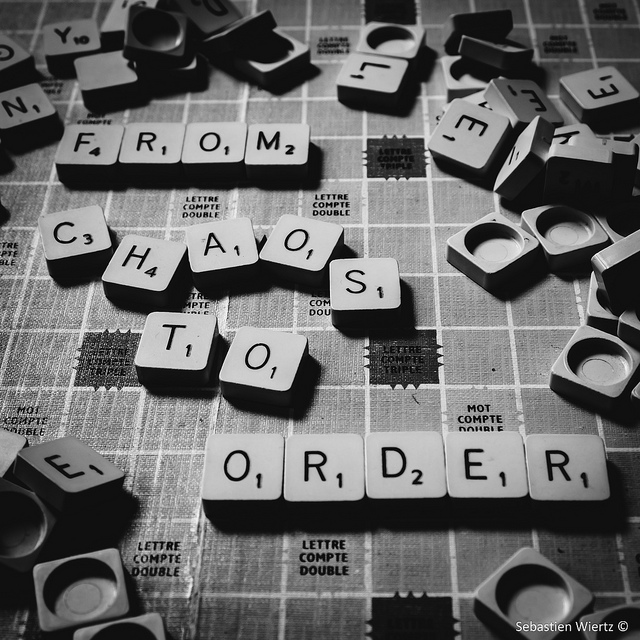

It was then I decided to retrain myself. I began to think of myself as someone other than the perpetual cock-up self I had come to know and loathe—someone deserving of love.

I promised—goddess forbid—to start letting things slide. If I forgot a name, misspelled the possessive form of “its” by adding a hasty apostrophe, didn’t fold the damned fitted sheet just so, I would remain peaceful.

It was hard. The first cover letter I sent to a potential teaching job (as an adjunct writing professor, mind you) I typed that I had “lead” (present tense) workshops instead of “led” them (past tense). That slacker spellcheck didn’t catch it, and neither did I. The familiar bilious wave of self-disgust rose up from my solar plexus (the chakral seat of self), but rather than allow it to overtake my entire being, I stopped and took a very long and very deep breath.

I told myself that it was all right. No, I probably wouldn’t get the job (no self-respecting university would give a job as a writing instructor to someone who has a typo in her cover letter), but that was okay. The typo has been corrected and there are always other jobs. I reminded myself that I was a good person with an iron-strong work ethic; this was just an oversight borne of excitement at the prospect of teaching what I love.

There were several more instances where I had to talk myself off the ledge, but over time perfectionism released me from its interminable grip.

Ten years later, I am a much softer being. Not One-Flew-Over-the-Cuckoo’s-Nest-McMurphy-post-lobotomy soft, but I have tempered the mania of perfection. Minutiae still has its beauty, structure still makes me feel safe, but they no longer define me. If my linen closet doesn’t look like the ones at The Plaza Hotel, I don’t have a stroke. These days, I’ve traded the obsession with details for bold swashes of love toward a fast-storming sky or a tree. I see myself as a part of a much grander and more significant whole.

I take delight in the larger picture of this life, not the pixels.

Most importantly, I have learned to be gentle and loving toward myself—and all my perfect imperfections.

If you find a typo in this article, please don’t tell me. I’ve already found it and am having a celebratory glass of wine.

Author: Rachel Astarte

Editor: Emily Bartran

Photo: Sebastien Wiertz/Flickr

Read 2 comments and reply