Our world’s need for self-soothing skills.

“Ba-ba bum, sh-sh-sh,” I gently chant as I bounce Sam slowly up and down. “Ba-ba bum, sh-sh-sh,” I repeat over and over, simulating the beating of my own heart, until he quiets and cuddles in.

He’s been a colicky baby who can be a challenge to soothe. But I’ve found a method that works more times than not. I pick him up and hold him against my chest so he can feel my skin and hear my heartbeat and smell me. He knows that I’m his mom and I think he has an idea of how much I love him.

I try to force my body to relax and become loose, because he can tell when I’m tense or stressed. Then we proceed to our rhythm of simulated heartbeats and walking around the living room, kitchen, hallway, down the stairs, up the stairs, again and again.

I’m trying to soothe and comfort Sam, not only so he’ll feel better, but to teach him so he’ll know how to do it on his own one day.

That was 13 years ago—today Sam is about to enter eighth grade. He’s smart, funny, exceptionally mature and unlike many kids his age, he knows how to soothe himself. He’s learned how to calm himself when he’s upset. He breathes deeply and slows his heart rate, relaxes and sometimes goes to sleep when he’s stressed.

But many of us never learned how to soothe ourselves, or if we did learn how, we forgot it somewhere along the way.

The need to self-soothe has its roots in our biological makeup. When we’re stressed, panicked or in pain, our hearts beat faster, our lungs take in air more rapidly and shallowly and adrenaline and other chemicals course through our bodies.

Once our stress response has been activated we’re physically—and emotionally—primed for more stress, and this leads to exhaustion unless we’re able to calm ourselves. We need to allow our parasympathetic nervous system—the mechanism in our bodies for calming—to work for us. To do that we have to slow down for a few minutes, breathe and change our focus.

Many people try to decrease their feelings of discomfort, distress or lack of control by drinking alcohol or taking painkillers. Eating disorders, overspending, extra-marital affairs and gambling are also common ways of trying to self-soothe.

Many young people today spend eight to 16 hours a day trying to soothe themselves with mind-numbing electronic activities. None of these attempts to self-soothe work. The discomfort remains under the surface, and the self-soothing attempts—the addictions and compulsive behaviors—lead to wasted time, decreased self-esteem, discontentment, and in some cases broken relationships, lost livelihoods, significant life disruption and even death.

Given all that, it definitely seems worthwhile to learn healthier ways to calm and soothe ourselves, rather than trying to avoid or numb ourselves to our distress.

Last night I took a long walk with my little dog. I’d had a day where I was pulled in all directions. I’d made the choice to do too much, which led to everything going wrong. Rather than stopping to breathe and self-soothe, I pushed through the day until I was frazzled and overwhelmed. I left work tired and on edge. I decided to go for a walk after dinner as a way to soothe myself.

It was a beautiful summer evening. The temperature was perfect, the sun was shining, the birds were singing their night songs. Day lilies were blooming in my neighbors’ yards. I drank in the sensations of that walk: the ground below my feet, the breeze on my face, the smell of freshly mowed grass. When I got home I felt soothed, as if the tough day I’d experienced had been wiped away.

What it takes to soothe an adult may seem different from what an infant needs to be soothed, but it’s essentially the same. Sensory information is still important. Just as my saying “Ba-ba bum, sh-sh-sh” to my infant son simulated the womb—or a comforting environment—for him, the birds and the neighborhood sounds on my walk created a comforting environment for me. The physical touch of the ground beneath my feet and the cool breeze on my face relaxed me the way holding my swaddled son against my chest relaxed him.

Healthy self-soothing is an act of kindness toward ourselves. And it’s an act of kindness toward others too. In the late 1980s, when restaurants were going smoke-free, I overheard a conversation between two people who were smoking. “What’s the big deal? They’re my lungs,” one of them said haughtily. By now even those people have probably heard about the health risks of second—and third—hand smoke. It’s time for all of us to think about the effects of second—and third—hand stress.

What is it like to work for an employer who is chronically miserable? Research has found these situations lead to rude behavior, less productivity and more absenteeism in employees. What is it like for a child to grow up with parents who are angry, withdrawn or removed from their children’s needs? Difficult at best.

Again, research has found that anxious parents often have children with higher rates of stress. Conversely, when parents decrease their stress, their children are shown to have increased growth, improved health, better grades and higher self-esteem.

One of the most responsible things we can do for others is to take good care of ourselves. We can’t expect others to do it for us. It’s up to each of us. But it helps all of us.

~

Relephant Reads:

How to Practice authentic Self-Care.

~

Author: Cindy Nichols Anderson

Editor: Rachel Nussbaum

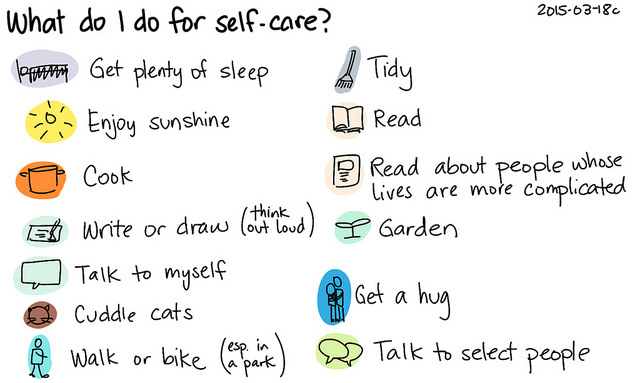

Photo: Sacha Chua/Flickr

Read 3 comments and reply