Sometimes I think I can hear my father laughing.

He had two truly distinctive laughs. The big, full body laugh that followed when he did something he thought was especially funny, and the slow, short chuckle that rumbled under his breath on a more regular basis when he teased or joked.

But it’s odd. When I try to remember or describe something like this, not only is it difficult to do with words, but the memory disappears as I try to focus. The harder I concentrate, the harder it is to remember. It’s like when you can see something clearer out of your peripheral vision. You turn your head to face it head on, and, poof, it’s gone again, and the harder you try, the more futile it gets.

It’s like that with my father’s laugh. I can hear it briefly, and I can see the shape of his jaw, the laugh lines in his cheeks, the slightly squinted eyes…but then I try to remember more, and the memory is gone. Only a shadow of a memory, existing in the periphery.

As my father was lying in bed at the hospital, after having the stroke that would end his life, I remember staring repeatedly at his trimmed fingernails. I spent a lot of time looking at those hands. They moved around a bit for the first couple of days even though he was not awake. He didn’t do much else but lie still and breathe heavily as if in a deep sleep, so I often stared at his hands and sometimes held them in mine.

Later, as he slipped further away, I would feel for his pulse to see if he was gone—finally and forever—and I would get even closer to those hands, my own pressed against the tiny evidence of his life.

And those trimmed fingernails.

He probably clipped them the morning of his stroke, before he got in the car to run some errands with the dog, which is where he was found, car idling and in park on the side of the road. Or at least the night before, based on how short they were and the way the fingers underneath showed new skin.

He would have been happy to die with short nails. He was so focused on hygiene and neat appearance, he would have been embarrassed to have nurses and doctors hanging over him if he had been sloppily groomed or appeared to have let himself go. Hands could reveal much about a person, he always said: the strength by which you shook hands, the ruggedness that came from hard work, the clipped nails that showed you took care of yourself.

During the week he was in the hospital, we went home a couple of times to shower, change clothes, and maybe nap before returning to the hospital. I remember seeing my father’s spare prosthetic leg in the corner of his room. The one he wore every day was, of course, on his body in the hospital. I looked at the spare leg with sadness. Despite being detached and inanimate, it was as much a part of him as his tattooed arms and flattened nose from his boxing days. Now here it was, loose and stationary, waiting for the connection of belts and straps to bring it to life when I knew that would never happen again.

When my father finally died, I remember looking outside of the hospital at the falling snow. Schools were cancelled, and most people were snuggled in bed with coffee or lounging around their living rooms watching TV.

We were huddled by his bed, nestled in our little pocket of misery.

The room seemed cut off from the world—cut off from the rest of the hospital even. The rest of my family cried when his pulse finally stopped, but I didn’t. I had been crying off and on all week as I had been losing him slowly. By the very end, he was just a weak heartbeat and a little blood running through some veins. That was not my father. My father had already disappeared at some point, but I really wasn’t sure when.

If one has a soul, when can we be sure it has escaped this world? I couldn’t pinpoint a time for my father during the days we spent by his side in the hospital. And I started to question the very nature of “soul” and life’s purpose.

I also questioned God. But I prayed that morning anyway. I prayed for my father, and I prayed for myself as I looked ahead to the looming years of my own life that would no longer include this great man I loved.

It’s been years since my father died. I’ve since come to conclude that souls do exist. They manifest themselves in people’s unique laughter and in the movement of their limbs and expressions on their faces. In the pieces of their physical selves and how they choose to present them—clipped nails and all. They abide in people’s beliefs and the truths they uphold, and how they bring everything they touch to life by their sheer existence. They show up in memories we have of them and stories we tell about them.

Souls exist in the love we had for them and still do.

And they exist in the love they had for us that we feel so intensely sometimes that it hurts.

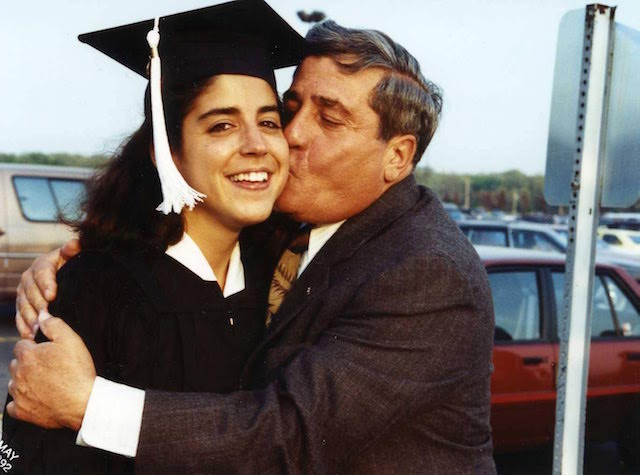

I tell my son Max that “Grampy kisses” were loud and strong. Grampy kisses involved big hugs, one hand wrapped all the way around to hold the side of the face opposite of the one being kissed, a sandpaper cheek scraping mercilessly. Grampy kisses showed the fullness of love with a smack so enthusiastic it hurt the ears. Oh, I hated Grampy kisses as a kid, but now I miss them. I try to give Grampy kisses as best I can to Max, but they can never be as loud or as sandpapery sweet.

And truly they can never be the same, because those kisses embodied a beautiful soul that can’t be duplicated. A soul that can only be remembered now—remembered and loved by those like me left behind.

Author: Heidi Parenti

Editor: Emily Bartran

Photo: Author’s Own

Read 0 comments and reply