Revelations that the former leader of Satyananda’s Australian ashrams abused children for decades have shocked the yoga community worldwide. Meanwhile, police are investigating the spiritual director of two more Australian ashrams amidst claims of sexual abuse. Is it time to do away with the guru model?

Well-dressed and articulate, former corporate high-flyer Sandra* knew nothing of yoga when her “stress doctor” recommended three weeks at Victoria’s Satyananda Ashram.

“I looked around and thought it was a cult,” Sandra recalls. “But Atma, the head of the ashram, made me feel safe. By the end of the trip the practice had worked its magic and I was hooked.”

Sandra went on to become a yoga teacher. Bolstered by the strength she found through her practice, Sandra eventually sought therapy to deal with sexual abuse she’d experienced as a child. “I relied on the ashram as a refuge,” she said. “The sense of community and belonging drew me in, especially when I felt I didn’t belong anywhere on the ‘outside’. I trusted Atma, and even though she was quite intimidating, she firmly held the space for people to work through their stuff.”

Last year, the Australian Government investigated sexual abuse at Satyananda’s other Australian ashram. Victims recounted decades of sexual abuse not only by the ashram’s spiritual head, Swami Akhandananda, but going back as far as Swami Satyananda himself. The youngest victim was six years old. Witnesses told of forced abortions, genital mutilation and being passed around to different teachers. It appears that many senior teachers knew what was going on and either looked the other way, or in some cases, directly facilitated the abuse.

Sandra recalls her horror on reading of Atma’s response to a former victim during the hearings. “A witness testified during the commission that she’d told Atma she was concerned about the Swami’s behaviour,” she says. “Atma said words to the effect of, ‘Well you know those girls can be very flirtatious.’ I was furious. As anyone who has been sexually abused knows, it is common to think it was somehow your own fault. I couldn’t believe that someone I trusted could have known something was up and chose to blame the victim. It felt like a betrayal.”

The list of gurus accused of sexual misconduct is like a roll call of the who’s who of the yoga community. From Swami Muktananda, Yogi Bhajan and Swami Satyananda, right up to Bikram Choudhury, Anusara’s John Friend, Kausthub Desikachar, and Kripalu Yoga’s Amrit Desai: sexual misconduct in yoga is so common Patanjali should have given it its own sutra.

How, we ask, in yoga communities built on the tenets of non-violence (Ahimsa), truthfulness (Satya) and sexual ethics (Bramacharya), can abuse still occur, let alone remain hidden for decades? Sadly, since news of abuse at Satyananda’s ashrams emerged, another two yoga ashrams have come under investigation by police, this time pertaining to allegations that the Director of Shiva Yoga centres in Victoria Swami Shankarananda (American Russell Kruckman) had inappropriate sexual relationships with up to 40 members of the community. Former members of the community describe being coerced into a sexual relationship with Kruckman, to be kept “secret in line with age-old Hindu Tantric scriptures” and threatened with being ostracised from the community if they refused.

Is it possible for communities affected by abuse to recover? Or is it time to re-evaluate the guru model?

Clash of cultures: the Eastern guru model in the Western yoga world

Former President of Yoga Australia, Leigh Blashki, has taken a leading role in establishing ethical codes of practice for yoga teachers and yoga therapists in Australia. Having dedicated much of his 35 year teach career to bringing traditional Eastern yoga practices to the West, he has seen first-hand how enthusiasm to adopt an “authentic” yoga culture can lead to the misuse of power.

“In Indian culture the teacher is held with deeper awe and reverence than we do in the West. Culturally, they’re taught not to question those with a perceived level of power. If the guru says, ‘I want you to do these things’ the assumption is the guru must know.”

Although in the West we are much more likely to question authority, we also have high regard for the concept of authenticity. Therefore, if a teacher announces that a certain practice is an authentic part of the yogic path, we may be less keen to question it. “Part of the marketing of certain yoga communities is we have a traditional Indian spiritual community, we wear saris, etc.” says Blashki. “I believe Russell [Swami Shankarananda] has taken those affects of Indian life which have suited him. I have no idea about his real self, but I can only suspect that if someone has genuinely had a form of true awakening, this behaviour doesn’t even enter into their minds.”

Is the Eastern idealisation of the guru something Western spiritual communities need to explore? This is an issue that the U.S. Buddhist community, The Zen Studies Society, was forced to grapple with after revelations that former Abbot Eido Tai Shimano had abused female students.

In the wake of the scandal, the organisation went through a radical change in values, says current abbot Shinge Chayat. In a journal article Confronting Abuse of Power, Chayat and other spiritual teachers spoke about the effects of abuse in spiritual communities.

Trouble begins, Chayat says “when no one is allowed to question things—especially in an Asian patriarchal structure that discourages transparency… We’ve had to learn how to question authority, and see all the aspects that led to a structure of a secret society and the elevation of one human being to a god-like status, which created a situation where no one felt safe to ask questions.”

Linking sexual abuse to “spiritual growth”

Swami Akhandananda’s victims told the investigation that he frequently cited the abuse as necessary for their spiritual growth. Similarly women involved in the Shiva ashram described how Kruckman initiated sexual relationships under the guise of spiritual attainment. “When he first approached me, I was outraged and horrified,” said Medha Murtagh, an ex-member of Shiva Yoga. “He explained to me that what was happening was ‘a shakti thing’ and was simply the natural unfoldment of our guru disciple relationship.”

“I would often talk to him about feeling that it was wrong for me to cheat on my partner, to which he would reply with things like, ‘You can’t look at it with worldly eyes. You’re exploring the Shakti with your guru and it’s not cheating.’ I was told not to talk about it to anyone, ever.”

Vulnerability and the imbalance of power

A common feature of many abuse cases is that the victims had often gone to spiritual centres as a refuge during times of great personal vulnerability. Many, like Sandra, had histories of sexual abuse.

In the five rape charges against Bikram Choudhury, some women have claimed that Bikram “rewarded male teachers who brought him willing consorts.” In 2002, after four women filed formal complaints with Austrian police about Kausthub Desikachar (grandson of Krishnamacharya), citing sexual, mental and emotional abuse, the North American branch of the Krishnamacharya Healing and Yoga Foundation revealed that Desikachar had used “his knowledge of personal histories of sexual and emotional trauma in an attempt to initiate sexual relations.”

“We’re looking at what can be seen as the worst abuse, which is sexual,” says Blashki. “I’ve never seen, nor heard of a good excuse. People say, ‘Well they were consenting,’ but when there’s a power imbalance, there’s absolutely no excuse. When people are fragile of ego and need to be recognised, it makes them feel attractive when the teacher shows particular interest in them,” says Blashki. “We need to educate newer students that ‘special attention’ from a teacher is not something they should be seeking, nor something that teachers should be offering.”

A culture of silence

In Shinge Chayat’s experience, elevating spiritual teachers to a noble height “can give rise to a situation where people are afraid that if they question something or speak out, they will be ostracised. What’s going on is often veiled in secrecy; practitioners may feel or sense something happening in a community, but the culture discourages questioning.”

Ex-members of the Shiva and Satyananda communities have spoken of the additional sense of betrayal they felt when community members chose to keep silent about the abuse, and effectively enabled it to continue.

“One of the more disturbing aspects was that some people in positions of power apparently knew what was going on and were actively trying to keep it secret and perpetuate the status quo,” says former Shiva member Stephanie*. After 17 years as part of the community, the revelations caused her to question everything. “If you’ve seen the film The Matrix, it was exactly like what happens when you take the red pill; I was suddenly falling down the rabbit hole into a harsh new reality where everything that I believed in and held dear was revealed to be an illusion. Each day brought more shocking revelations, and it hasn’t stopped yet. I thought I was a member of a loving community in a beautiful special world, but it was really just the mask over a nightmare.”

The ‘Orphan’ Archetype

Yoga teacher and psychotherapist Stephen Cope knows better than many what it’s like to have this illusion shattered. In 1994, he had lived at the Kripalu Yoga Fellowship for almost 10 years when the community was rocked by their beloved teacher Amrit Desai’s admission that he had had sexual relations with numerous female followers.

In his book Yoga and the Quest for the True Self, Cope writes about the “orphan archetype,” which is common when people come to a spiritual community seeking an idealised idea of family. “‘Orphans’ bring a tremendous amount of projection into their relationships with their teachers,” Cope writes. “We fall in love with our teachers, and with our communities, and as a result we do not see them at all clearly.”

Beyond human

The problem is that this projection often goes both ways, says Cope. “If the teacher is not aware of his own unresolved needs to be highly praised, and adored, he or she may begin to believe the idealisations of the students.”

“We tend to elevate teachers to a noble height and refuse to see their human failings until they have manifested in difficult and dangerous ways,” says Chayat.

When the teacher and student are unaware of own subconscious motivations (whether it’s the student’s desire to surrender their will, or the teacher’s desire for admiration), “it is only a matter of time before the situation collapses under its own weight,” Cope writes. “The powerful forces of idealisation are suddenly transmuted into a bonfire of devaluation, hatred and rage, usually coming on the heels of some dramatic revelation that the teacher, the hoped for god-man or god-woman, is really all too human.”

Is there an ideal Guru-student relationship?

“My teaching is a method to experience reality and not reality itself, just as a finger pointing at the moon is not the moon itself,” the Buddha famously said.

During my own yoga teacher training, I was taught that the teacher’s role is to encourage students to develop a relationships with their own “inner guru”—not just the teacher’s. What struck me in researching this article was how, over and over, students were actively encouraged to surrender this inner wisdom to the guru.

Ideally, says Cope, the guru stops this from happening via “optimal disillusionment.” “The best teachers eventually leave the students, or demand that the students leave them (while still being available for occasional “refueling”), precisely so that the student can discover and rely on his own connection with the source. The teacher’s final role is to awaken the lotus of the heart, so that the student’s own consciousness is called forth.”

Respect without worship

Sadly, some practitioners feel that the yoga taught by their former guru is tainted. However one yoga sangha that has not only survived, but thrived, is the Bikram community. One Bikram studio owner I spoke to said it helps that the general public are largely unaware that the “Bikram” is actually a person. And while studio owners respect the trademarked practice, some now actively disassociate themselves from Bikram himself, and have quietly removed photo of him from the studio.

Is there a way to pay respect to our current teachers and lineages while resisting the urge to elevate them into demi-gods? One way would be to focus on the principles of the practice, rather than the deifying the personalities behind them. Many yoga centres feature prominent images of their gurus, living and dead, and invoke their names in chants and prayers. But does this focus on an individual encourage an inappropriate “mistaking the finger for the moon,” or is it a natural aspect of Bhakti Yoga, the yoga of devotion?

“From the Western perspective acknowledging our teachers is still important,” says Blashki. “But you can explain where certain teachings come from without putting the teacher’s photo everywhere. This can come across as the hubris of either the teacher or the student who aligns themselves with them.” In some cases ostentatious devotion can actually be a hindrance. “I’ve seen many out there effectively held back from reaching their own potential and discovering ‘who I am’ as a teacher because it’s all about devotion to the guru.”

How can communities regain trust?

- Step down

While spiritual leaders who either perpetuated or condoned the abuse remain in power, it is hard to see how a spiritual community can retain trust among students, let alone credibility. This can make or break a community; if the community revolves around something more than just one person, it has a better chance of survival.

- A genuine desire to listen

In order to move forward there must be genuine acknowledgement of wrongdoing and the pain people have suffered—rather than: now that we have been found out, we’re going to be apologetic. When some victims from Satyananda’s ashram first came forward, they were threatened with legal action. Eventually the organisation offered a “Haven [fire ceremony] for healing,” although, as one former child victim at the Satyananda ashram bluntly told the Australian Government investigation, “I don’t think that they can just light a fire and say, ‘Hari om’ and think that everything will be forgiven and forgotten.” More recently, however, The Satyananda Yoga Academy have set up a task force to respond to the investigation’s findings.

- A peer group for spiritual teachers

“All teachers ought to have a clear supervisor, like psychotherapy,” says Blashki, who has his own supervisor and acts in that role for junior teachers. “Sangha is important, but it’s quite different to supervision, where the person being supervised is really called to account with a depth of honesty of sharing that often can’t occur in sangha.”

“As teachers, we need to be very conscious of what our own emotional and psychological needs are, and we need to try and meet those in healthy ways rather than pretend they’re not there,” says Lama Palden in Confronting Abuse of Power.

- Engage a third party + separation of power

“When all the power in a community is in one person’s hands and that person is supported unconditionally by others, including board members and senior students, there’s no way you can say, ‘Hey! This is wrong. We have to make some changes here.’ It can’t happen,” says Shinge Chayat, who as a member of The Zen Studies Society leadership created an ethics committee which sits separately to the board.

One of the problems within the Shiva community, says Stephanie, was that “the very people in charge were exactly the ones who shouldn’t be there. When a demagogue decides to surround himself with yes-men then this is what you get, and in the world of yoga the very principle of the guru practically guarantees it.”

By contrast, the Kripalu community has flourished in the wake of Amrit Desai’s departure, due in no small part to their engagement of a neutral third party to help them re-assess and recognise their leadership structures.

But for some, nothing can repair the betrayal of trust by their teachers and senior members of their yoga communities. “It is time for us all to do away with the modern myth of The Guru,” says ex-Shiva member Stephanie. “It has failed over and over, leaving thousands of wounded people in its wake.”

Medha Murtagh agrees. “Teachers and mentors are great, but I will never again surrender to an individual who claims to be closer to God than me. I don’t think God would have designed the universe so that we’d need a middle man to access him! My personal experience tells me that the age of the guru is over.”

For many modern yogis, the very word guru is a relic, with its 1970s connotations of free love, communes, and tasteless lentils. But have we simply replaced the guru with the “super teachers” feted on Instagram? Have we shaken off guru-worship only to replace it with worship of the “yoga-lebrity”? Is there still room, in this vortex of yoga-selfies and branding, for the inner teacher to reign supreme?

*Some names have been changed.

~

Relephant:

How to end Sex Scandals in the Yoga Community.

~

Author: Alice Williams

Editor: Travis May

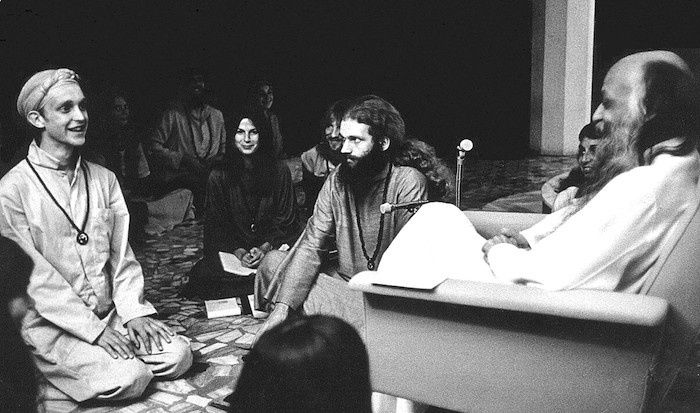

Photo: Wikipedia

Read 15 comments and reply