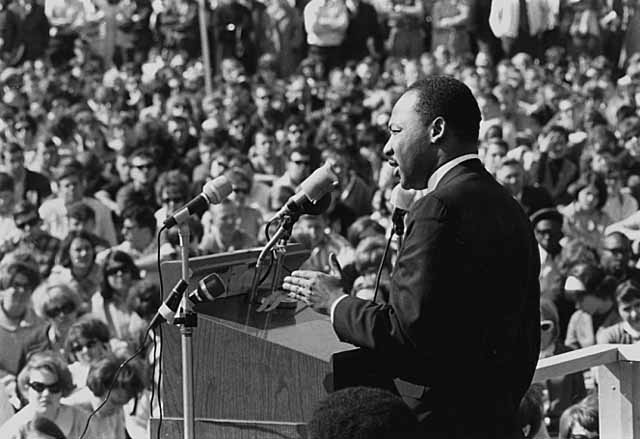

While Martin Luther King was walking across a certain bridge in Alabama, I was walking through Watts, California with a suitcase full of samples in my hand.

“You a social worker?” a little dark-skinned boy on a bike called out to me, but I think he was asking more so he could show off how fast he could skid his bike to a stop than whether I was a social worker or not.

I had just parked my car in a street lined with what are still called California bungalows. It was dinner time and I could smell the greens and pork wafting from kitchens with windows that looked out over carefully trimmed lawns. There was a soft California sunset, the kind that seems to go on forever and I was looking forward to my appointment just a few doors away.

“You’d be really good at selling,” my neighbor Judi had said one afternoon while we were watching our kids play in her twice-as-big-as-mine-even-though-we-were-neighbors back yard. Judi had lots of money and didn’t miss a chance to show it—like when the vacant lot adjacent to her house went up for sale and she and her husband bought it and filled it with swing sets and tree houses and the ultimate sign of 1965 prosperity, an above-the-ground swimming pool.

“We just wanted our kids to have more room to play,” she said.

I wouldn’t have minded having a little more room to play myself, I thought. Except I’d buy a new clothes dryer with my money so I wouldn’t have to hang the clothes out on the line every day, or so I could put sausage in my spaghetti sauce instead of the interminable cheapest hamburger money could buy.

It’s not that I wanted something like an above-the-ground swimming pool or anything.

So what Judi was proposing—direct sales for her father’s waterless cookware company—was interesting to me. I could do it part time after my husband got home from work with the car. I still even had a list of all the girls I’d graduated from high school with who I could call for leads.

I did the training. I easily learned how to make cold calls and how to make a hard close and Judi was right. I was good at selling.

For the first six months in fact, I was so good at it that I was the top selling rookie on the team.

Apparently however, being the top selling rookie on the team in the first six months wasn’t good enough for Judi’s dad because it took him just about that long to call me into his office to give me the talk.

“I don’t want any more of that “n*gger paper you’re bringing me,” he said straight out. Adding that if I didn’t stop selling in Watts why, I could just go out and find another job.

I had one month to clean up my act.

What?

According to Judi’s father I wasn’t really selling pots and pans. I was selling financing and Judi’s father was the finance company. According to him, “N*ggers finance everything and then don’t pay their bills.”

According to me however, I wasn’t selling pots and pans or financing. I was selling an idea or a hope for the future. I was selling a dream—a dream of a new life that just happened to look like new pots and pans.

“You want to have a kitchen full of pots and pans that are nice and clean and shiny, don’t you?” I was asking the young black woman sitting across from me. Holding up a three ring binder full of pictures that supported my pitch, I showed her a kitchen cupboard full of burnt, mismatched pots and pans all crowded into a too small space in an imaginary kitchen.

“This isn’t the kitchen you dream of when you think of yourself being a new bride, is it?”

It certainly wasn’t the kitchen I’d dreamed of myself. Why would it be the one she dreamed of?

“How much is it worth to you to have pots and pans with the new space-age, waterless technology that means vitamins and minerals stay in the food and aren’t leached out into the water in the pot?”

Almost every young woman I called on agreed with me.

But $99.00 was a whole lot of money in 1965 and I was mostly selling to young women who were a little younger than me, not yet married and helping their moms and dads pay the mortgage with their wages.

“I want to help my parents but I also want to go to school. I can’t afford something so nice as these pots and pans.”

They could afford it, I’d say. We had a $9.99 per month payment plan. We’d just keep the pots and pans for them until the first six months was paid off.

To me it looked like win/win.

The young woman sitting across from me on the sofa with the hand crocheted doilies on it and the smell of greens and pork wafting from the kitchen would end up with a brand new set of matching cookware and I would end up with a brand new clothes dryer and extra money to buy sausage for my spaghetti sauce.

“And, oh yes,” I added, “If you give me the names of five of your girlfriends who you think would like to learn about this new space age waterless cooking way of life, I’ll throw in a four-piece place setting of silverware for free!”

Yes. Like Martin Luther King, I too had a dream. And sitting there that day across the desk from that big, powerful white man with the daughter who was my neighbor with the extra big back yard when he told me to stop bringing him “n*gger” paper felt to me like he was stealing that dream.

The funny thing about it all is that I honestly believed in my product and in what I was doing. It may have been my naivety but I was a child of the 50s and I honestly thought that a matching set of pots and pans—that a woman paid for herself, out of her own money—would make a difference in her life. That she would be proud that she’d bought them for herself and that her money and her effort wouldn’t be wasted and that the pots and pans would last a lifetime to boot.

After my meeting with Judi’s father though, I didn’t want anything to do with him or with her any more.

They suddenly looked to me like the people lining the streets in Birmingham that I’d seen cheering as the police set the dogs and high pressure hoses on children and high school kids. I’d seen it all live. On TV.

Judi’s father with his constant referral to n*gger paper made me feel like he was holding one of those hoses and he wanted me to grab hold and help.

I didn’t grab hold. Instead, what I did was call the County Attorney’s Office to tell them what Judi’s father had said and what he was doing and to report it as a crime. But of course, it wasn’t a crime. Not in those days.

I thought about all the girls who I’d sold pots and pans to. I thought about how they thanked me for my “advice.”

I thought about the young woman who’d deliberately taken my hand before I left and, looking down at our clasped fingers had said,

“We may have different colored skin. But inside both of us have red blood.”

I thought about the young woman who, when I told her my mother from Italy used to call greens and beans “food for the soul,” said her family called it “soul food” and insisted that I take a Tupperware full of soul food home with me.

What I ended up doing was calling the NAACP. They listened to my story and sent me a form to fill out and when I sent it back to them they told me they’d “look into it.”

But I don’t think they ever did.

They had bigger pots and pans to deal with in those days—Martin Luther King was marching.

I remember thinking that the civil rights movement would bring about enormous change and that the world would be a different and better place when it was over—a place with no room in it for the likes of Judi’s father.

I remember feeling like I had contributed something. I may have lived thousands of miles away from Birmingham but I hadn’t let a racist intimidate me. I had quit my job and I told him why I was doing it.

“Not because I can’t sell cookware,” I said. “But because I don’t like the ‘N’ word and I’m not going to work for anybody who uses it.”

He offered me a larger commission and a different territory if I would stay.

“No thank you.”

I went home feeling like I had walked across a bridge in Birmingham myself and that I was gonna keep walking across that bridge anywhere I saw it, until I finally got to the other side.

Even today I am aware that bridge hasn’t been completely crossed. But those of us who marched with Martin Luther King—in whatever way we marched—are still on it. Still on the path. Still walking forward with a dream.

A dream that is still shiny and new and that still comes with a lifetime guarantee.

Relephant Read:

4 Awesome ways to Deal with the Awkwardness of Racism.

Author: Carmelene Siani

Editor: Catherine Monkman

Photo: Wikipedia Commons

Read 0 comments and reply