Many of us turn to yoga and meditation in hard times; there is nothing like a loss or heartbreak to bring us crawling back to our cushions and mats.

But writing, for me, has been just as redemptive.

My writing practice helps me to process the broken parts of the world and the beautiful parts simultaneously. It helps me to express on the outside what I’m experiencing on the inside, allowing me to step out of the wheel of my ruminative thoughts and find peace. At 28, keeping a journal even helped me to recover from PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder).

The story is this:

I had been traveling for almost three months in Africa when I was carjacked in Kwazulu Natal by three armed men. One of the men held a gun to my head, ordered me out of the car and instructed me to run into the woods. Terrified, I sprinted, the gun aimed at my back. I dove into a ditch, and the car screamed down the road with all of my belongings. I was left physically unharmed, but mentally and emotionally, I was shattered. I stood on the side of the road in shock, with nothing but the clothes I was wearing.

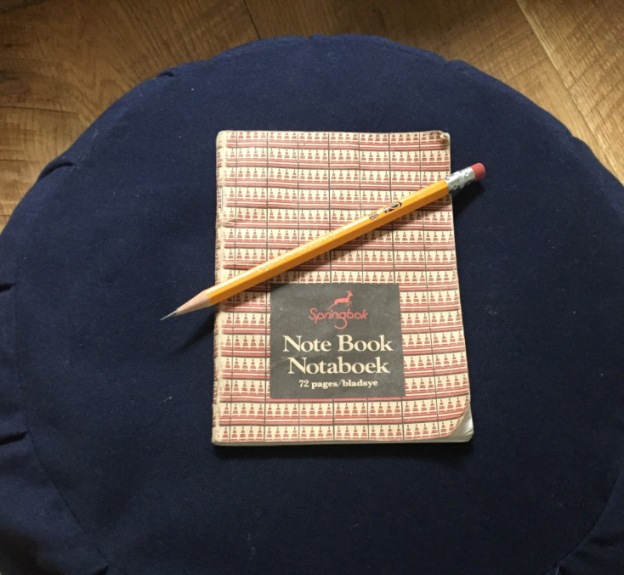

I made my way back to Johannesburg and was loaned the equivalent of $20.00 to last through the weekend, until money could be wired from the United States. I walked to a convenience store and bought some essentials: a toothbrush and toothpaste. And then I bought the most essential thing: a little notebook to replace my journal that had been stolen.

James Pennebaker, a professor of psychology at the University of Texas, Austin, says that “by writing, you put some structure and organization to those anxious feelings. It helps you get past them.”

In Johannesburg, writing was my lifeline. I documented the guns, the men, the terror, the trees. One of my mentors, the beautiful short story writer, Lucia Berlin, said, “When I first started to write, I was alone. My first husband had left me, I was homesick, my parents had disowned me because I had married so young and divorced. I just wrote to…to go home. It was like a place to be where I felt I was safe. And so I write to fix a reality.”

That little journal I bought in Johannesburg was exactly like that, like going home.

It was a safe place when I was traumatized and vulnerable. I wrote in the airplane back to New York. I wrote when I got back to Boulder. I wrote to make sense of the carjacking. I also reached out for help in other ways: I went to a psychologist who specialized in EMDR, a PTSD treatment that helped to relieve my flashbacks. And I enrolled in Richard Freeman’s month-long yoga teacher training program, an experience that was transformative in uncountable ways. But writing, for me, was always the underlying practice, the core practice.

And research backs up my experience. Pennebaker started studying the power of expressive writing in the 1970s and 1980s. It was already known that people are more prone to depression and sickness after trauma. But Pennebaker discovered that that people who kept their stories secret were much worse off than those who didn’t. He wondered if writing would help people process their experiences, if it would help improve their health. Almost 50 students signed up for the first experiment, and the results were stunning.

The students who wrote about emotional upheavals in their lives made 43 percent fewer doctor visits in the weeks and months after the study than those who had been asked to write about superficial topics.

Since that first study, over 300 more studies on expressive writing have been published, and in all of them, participants who wrote about significant events in their lives experienced better sleep, less pain and anxiety, and improved immune systems in the weeks and months following. They also reported feeling happier and less negative than before.

For me, my regular writing practice centers me in my body and my emotions. It gives me a broader perspective as well, a deeper sense of meaning in my life and my path in the world. Fifteen years after the carjacking, I have a record of what I’ve been though and how far I’ve come. I savor my poignant memories, and I am more conscious and grateful in the present. I know that no matter where I am in the world, or how difficult the circumstances, I have the tools to carry me through. I can always write. I can always go home.

Author: Ashley Shires

Image: Courtesy of Author

Editor: Catherine Monkman

Read 0 comments and reply