{Cutting Through} is a new bi-weekly column on elephantjournal.com. Have a question about meditation, mindfulness, or Buddhism? Please send it to Travis at [email protected] or in a comment on this article. Travis is an authorized meditation instructor in the Shambhala Buddhist lineage and the Center Director of Shambhala St. Petersburg. He is a joyful student of Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche.

Question: Something I struggle with is wanting my intentions behind meditation to be pure. I don’t want it to be like, “Oh I’m doing this because I want to feel better or be more focused and productive” or something—or because it’s the hot thing to do. But I feel like I’ll never reach that perceived/mind-created level of purity for me to feel honest in doing it. What should I do?

~

People begin practicing meditation for many different reasons. Now that Western science is measuring and publishing the beneficial effects that meditation has on our lives, whether it be to lessen anxiety or depression, improve sleep, or reduce chronic pain, meditation is attracting more and more people interested in benefiting from a mindfulness practice.

When I teach our Learn to Meditate class at our meditation center, we begin by going around the room to introduce ourselves and telling a little bit about what brought us to the meditation center. People commonly respond by saying that they wish to lower their stress levels or that they wish to slow down and quiet their busy minds.

For myself, I became interested in Buddhism by reading the books of Alan Watts, and then Chogyam Trungpa. I became more interested in the result of the practice and path of Buddhism first, and by being intrigued by the brilliant, awake minds that studied the teachings deeply and then expounded upon their experiences in profound and esoteric writings.

So, when I began the path of Shambhala Buddhism, meditation was more of a hoop to jump through to get where I wanted to be, rather than something I had a strong desire to do in itself. (But, after some time, it became the best thing I had ever done…in itself.)

All this to say, there are many reasons people begin to meditate. There are many—now scientifically proven—benefits to practice, so naturally many people are starting to read and learn about and become interested in giving it a try.

All of the reasons listed above are valid for learning to meditate; the bottom line is that meditation helps with many different areas of concern, and if we’re looking for help in one of these areas, then meditation may be a good option.

In some sense, we need not make our meditation practice into something too precious. A pure intention is one without a lot of contrivance. It’s a process of coming down to Earth and letting go of self-deception.

In many ways, meditation is much akin to behavioral therapy. We’re learning to break our habit of being led around by our discursive, undisciplined mind (which because of these qualities causes us a lot of discontent and other negative feelings), and learning to relax into the natural contentedness and well-being that is our natural state—when we disentangle ourselves from the jungle of our monkey minds.

The process of doing this, which is the technique of shamatha (described below), is what leads to all of the health benefits that Western science is now confirming and documenting. Whatever our reason for beginning, if we practice the technique in a genuine and consistent sense, the various benefits will inevitably begin to occur as byproducts of our intention for practicing.

What is the technique, and what does it mean to have a genuine and consistent practice?

It is recommended that people receive teachings in person from a qualified teacher of meditation. There is an oral tradition and lineage dating back to the time of the Buddha 2,600 years ago of receiving the transmission of the practice from a living teacher who can guide you through the practice and help you with obstacles as they arise. That being said, here is a brief description of the technique from my teacher, Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche:

We approach our meditation seat as if it were a throne in the center of our life. By taking an upright sitting posture, we enable the body to relax and the mind to be awake.

On a cushion or a chair, take a balanced, grounded seat. On a cushion, sit with your legs loosely crossed. In a chair, keep your legs uncrossed and your feet flat on the floor.

Imagine a string attached to the top of your head, pulling your spine erect. Let your organs, muscles and bones settle around your uplifted spine, allowing the energy in the center of your body to move freely. Slouching impairs the breathing, which directly affects the mind.

Place your hands on your thighs, palms down. The fingers are close to each other and relaxed.

Tuck your chin in gently and relax your jaw. Relax your tongue; rest the tip against your upper teeth. Let the mouth be slightly open. Gaze downwards with the eyelids half shut.

In peaceful abiding, the object of meditation is the act of breathing. By resting the mind on the breath we train in staying present and mindful. So now become aware of the breath. Stay with the feeling of the breathing. Breathe normally.

If you space out or lose track of the breath, count the in-and-out cycles of breathing. Once you’re more focused, drop the counting and focus on the air moving in and out, which allows some steadiness in contrast to our usual mental discursiveness. It also helps us relax. As our thoughts slow down and we settle into ourselves, our body and mind become synchronized.

We’ll notice that even as we rest our mind on the breath, thoughts and emotions continue to distract us. We may become swept away and forget that the breath—not our fantasies, emotions and discursive thoughts—is the object of our meditation. When we notice that we’ve been distracted by our thinking, we acknowledge it, either silently or by labeling it “thinking.” In either case, we bring our minds back to the breath. We acknowledge the thought, allow it to dissipate and return to the breath.

It’s important to remember that the technique of peaceful abiding involves gentleness as well as precision. Gently coming back to the breath will help us appreciate the basic quality of who we are. And we need precision to remember to apply the technique without judgment or analysis. We simply recognize thoughts as thoughts, and without being distracted by them, return to the breath. The instruction is really pretty simple: When you lose your mind, come back.

To practice genuinely (as much as we are capable—which changes over time) is to honestly work with the technique as much as possible. No one really knows what we’re doing when we’re sitting there on the cushion staring at the ground, but if we are interested in finding the result we are seeking, we do actually have to do the practice.

Also, changing the momentum of our conditioning and habitual patterns takes time—years and years. There is also the notion of consistency. As we don’t get physically fit by lifting 10,000 pounds at once, we need to consistently practice daily (or close to it) in small doses over a period of time. Beginning with 10 to 20 minutes a day is a good place to start. Practicing for even five minutes a day is better than practicing for 40 only on Sundays.

The Sakyong has said that it’s important to set our intention before each time that we sit. Otherwise, it may become just a rote routine that we do without thinking—just going through the motions without really working with the technique.

So, whichever part of our minds or experiences we wish to work with, that is the intention we can set before we begin to practice:

I am going to work on my ability to focus on the task at hand.

I am going to try to feel the space between thoughts and rest in that.

I am going to allow myself to feel my chronic pain and not resist it.

I am going to learn to appreciate this moment that I am actually living and be content with that.

I am going to let go of the recurring thoughts that are driving me crazy.

I am going to think about cute girls at the beach the whole time.

Well, the last one sounds like the best one, but it’s probably not going to help us tame our neurotic minds.

We could also think a little bigger.

Meditation can help clarify some of life’s biggest questions and fundamentally change the way we experience our lives. We are conditioned to live in our heads, to jump in discontent from thought to thought, from thing to thing. We are often made to feel inadequate, unworthy, and incomplete. The good news is that none of that is true, and that we can discover our innate sanity and rest in it.

What I have learned from studying the teachings of the great teachers of the past and present, and then through my personal experience, is that underneath the stormy weather of my neurotic and self-defeating mind lies the clear sky of health and well-being. When we directly and gently work with causes of our dissatisfaction and suffering in this way, we start to unravel the momentum of our past habits and find wonderful, life-affirming qualities, such as, contentment, peace, spaciousness, healthiness, confidence, and so on.

We can change the ineffective ways we relate with concept and language, with thoughts of life and death, with ideas of self and other. We can join the lineage of awakened warriors, and attempt to leave this world a better place than we found it.

The big picture and the more mundane reasons we are drawn to practice are not in conflict. They are both steps along the same path leading to the same place. It is the journey from here to here. In the end, as T.S. Eliot said, it “will be to arrive where we started, And know the place for the first time.”

Meditation is a process of becoming familiar with our own minds and lives. The main point is to keep doing that. Any intention that helps you get there is a good one.

At some point, the momentum swings in the opposite direction and more and more of our lives can be spent experiencing our innate health, contentment, and joy.

~

~

Relephant Read:

{Cutting Through}: The Four Noble Truths. Isn’t suffering important for growth? {Weekly Q & A}

~

~

~

Author: Travis May

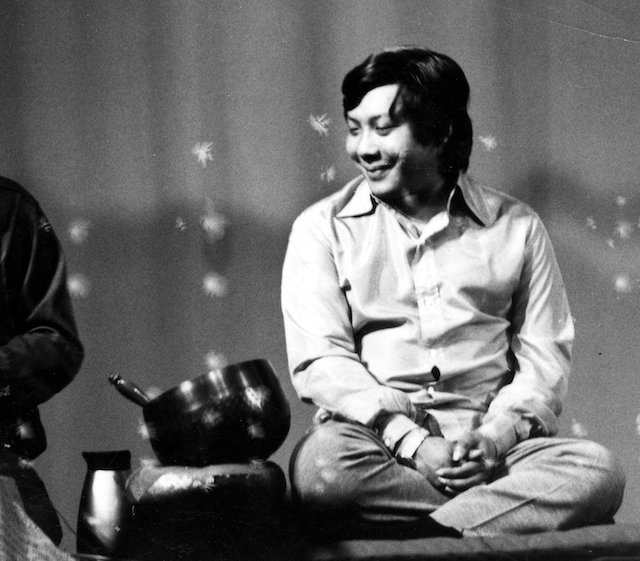

Image: YouTube

Read 1 comment and reply