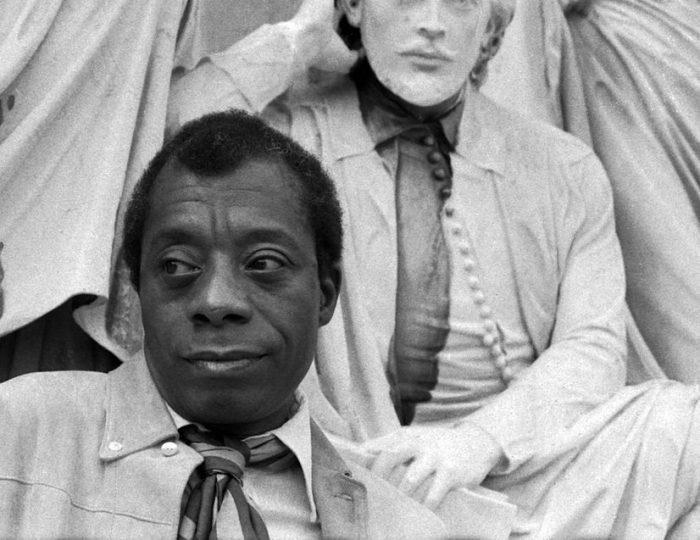

As we steadily approach the birthday of one of the most prolific and prophetic writers of the 20th century, James Baldwin, I can’t help but feel that his words are more chillingly relevant than ever.

These are strange times. The culture wars in this country continues to accelerate at terrifying speeds, with each passing day providing yet another controversial clickbait headline for us to fight over—feeding the fire further still.

We are losing our cohesion as a nation, as the political center has been replaced by a toxic strain of identity politics on both the left and the right that is polarizing the Western world, splitting us at the seams. The ability to speak the same language is fading away. The founding notion of our country—that we can reach a consensus through honest discourse—is steadily becoming a thing of the past.

In some ways, the future feels bleaker than ever before.

As a young person clumsily navigating the treacherous waters of modern politics, it can be difficult to understand where all this conflict comes from. I’ve been doing a bit of research into our history of late, and I’m finding that much of what we see in the world today is cyclical—an echo of past events. Nothing happens in a vacuum, although many of us would like to believe that “Trumpism” is some kind of cosmic mistake. You see, the past is not dead, it’s an active force in the world—and very few have illuminated this more than the late, great James Baldwin.

Growing up in Harlem during the days of segregation, Baldwin used his voice to shed light on the struggle of the American Negro and take the country to task for its long-lived willful blindness of the “racial problem.” Through a synthesis of eloquently portrayed personal anecdotes and cultural commentary, Baldwin continues to speak to our common humanity in a tone that both uplifts our spirits and at once gives us chills.

Among his intellectual contributions, Baldwin outlines the underlying psychological mechanisms of racism with such sharpness and depth that we can’t help but be faced with our own shadow. That was his genius, and perhaps in heeding such a voice, we can move through the murky swamps of modern culture more gracefully.

Take a few moments to let his words sink their teeth into you:

1. “What’s happening in the mind of the poor white man and the poor white woman is this: They’ve been raised to believe, and by now they helplessly believe, that no matter how terrible their lives may be, and their lives have been quite terrible, and no matter how far they fall, no matter what disaster overtakes them, they have one enormous knowledge in consolation which is like a heavenly revelation…At least they’re not black.”

Racism has very little to do with how we might feel about a different culture or skin color—that is merely what’s happening on the surface. It’s more subtle. The truth is, racism is really about having someone below us to fall back on, an “other” who gives us a sense of power with a sense of divinity as well.

We convince ourselves we’re “more human” than another group, like we’re closer to God. The truly terrifying thing about racism is that it actually makes sense—successfully boosting the morale of one race at the expense of another. What we have failed to see throughout history, and still fail to see in many ways, is the psychological cost of living in such a way, as the damage done to our collective soul is irreparable.

2. “He doesn’t know what drives him to use the club, to menace with the gun, and to use the cattle prod. Something awful must have happened to a human being to be able to put a cattle prod against a women’s breast. What happens to the women is ghastly…What happens to the man is in some ways much much worse.”

We create the “other” to uphold our sense of “self,” but what we don’t understand is that we are the “other.” What we do to another, we do to ourselves.

It’s as though we’ve been looking at ourselves in a mirror through thousands of years of violence and persecution. And a nation predicated on such a performative contradiction is one that eats itself to death.

3. “What you have to look at is what is happening in this country, and what is really happening is that brother has murdered brother knowing it was his brother. White men have lynched Negroes knowing them to be their sons. White women have had Negroes burned knowing them to be their lovers. It is not a racial problem. It is a problem of whether or not you are willing to look at your life and be responsible for it, and then begin to change it.”

Can you imagine: one of the most quoted figures in social justice claiming that what America is facing is not a racial problem? That’s something I’ve had to wrap my mind around. To look at the problem purely in terms of race is incredibly limiting—it doesn’t allow us to solve anything.

If it’s all about race, and the world is just a massive power play between different groups, then why have the conversation? I believe Baldwin understood the moral relativism that comes with groupthink. We can only contend with the “racial problem” by going beyond race. I don’t mean this in the neoliberal “colorblind” sort of way, but in a deeply psychological sense, as we observe our propensity to project our own suffering onto other people.

This is the appropriate level of analysis—acknowledging the universality of racism, or more specifically “other-ism,” and taking the steps to identify how it moves through us. Contrary to popular belief, calling someone a “racist” is entirely useless, just like calling someone a communist during the Red Scare, and it goes completely against the ethos of Baldwin’s argument.

4. “The very dangerous effort one has got to make, according to me, is to deal with other people as though they were simply human beings. To remember that no matter what the details of their lives may be like, or how different they may seem to you superficially, or what the social pressures outside of what the psychological pressures are within, to deal with this other human being precisely as though he or she was here for the first and only time. To deal with them in some way that you’d like them to deal with you, no matter the price. From my point of view, no labor, no slogan, no party, no skin color, and indeed no religion, is more important than the human being. The human core in everybody, which liberates you and me, because when the chips are down this is all there is—there isn’t anything else.”

Not only does Baldwin explicitly identify the mechanisms that perpetuate racial injustice, he also puts forward a potential solution, something that few modern scholars do. If what’s really happening is a kind of “other-ism,” a projection of one’s inadequacies onto another, the denial of our common humanity, then perhaps the only change we can make in our daily lives is a reversal of this process—a conscious “going out of one’s way” to recognize the vital essence of everyone we come in direct contact with and the fundamental humanness that we all share.

This may sound naive or unrealistic, but the fact is that it’s totally practical , for once we connect with our own humanness, our own spirit, our own intimate sense of aliveness that is common to all, we can begin to unearth those qualities in other people.

5. “The question you gotta ask yourself, the white population of this country has to ask itself, is why it was necessary to have a ni**er in the first place. I am not a ni**er…I am a man. If you think I am a ni**er, it means you need it, and you gotta find out why…And the future of the country depends on that.”

There is a feeling of hopelessness in the country at the moment, as though it’s only going to get worse from here, and that feeling is fueled by the conflicting narratives of mainstream media—much of which operates along the same lines of the ideas Baldwin discussed. Those on the left seem to believe we should all be ashamed of ourselves for systemic racism and our oppressive history, purporting white guilt to be the central political tool necessary in creating change. The right, on the hand, is either indifferent to racial issues or embodies a “pick yourself up by your bootstraps” sort of an attitude—neither of which cut to the core of the problem.

I don’t think the world is falling a part, but I do believe it is, in the words of Baldwin once again, “a very grave moment for the West.” Until we can start talking to each other again about serious matters, sincerely and considerately probing for an answer, as we have at times in the past, then perhaps the sins of our ancestors will prove to be our downfall.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cbtFtcz4HFs&t=6s

~

Relephant: The Simple Buddhist Trick to being Happy.

Read 2 comments and reply