View this post on Instagram

*Read here why Miley Cyrus is facing major backlash after posting photos lounging in a Joshua Tree.

~

Your public lands hate you.

Seriously, they do.

And no—hate isn’t too strong of a word.

Hear me out. Do you post pictures of national parks, state parks, or other public lands on the internet? Do you geotag those photos? Do you go that extra inch to get the perfect Instagram-worthy shot? Has the environmental impact of what you post online never crossed your mind?

If you answered yes to any of those questions, your public lands do indeed probably hate you.

Image: Instagram

I’ve been an avid user of our public lands for the last 25 years of my life. I started hiking with my father when I was five-years old. He transferred his love of the outdoors and taught me much of what I know now. I’ve been to every national park in the lower 48, backpacked around some of the most remote sections of our country’s wilderness areas, and rafted/canoed some of our most beautiful rivers and lakes.

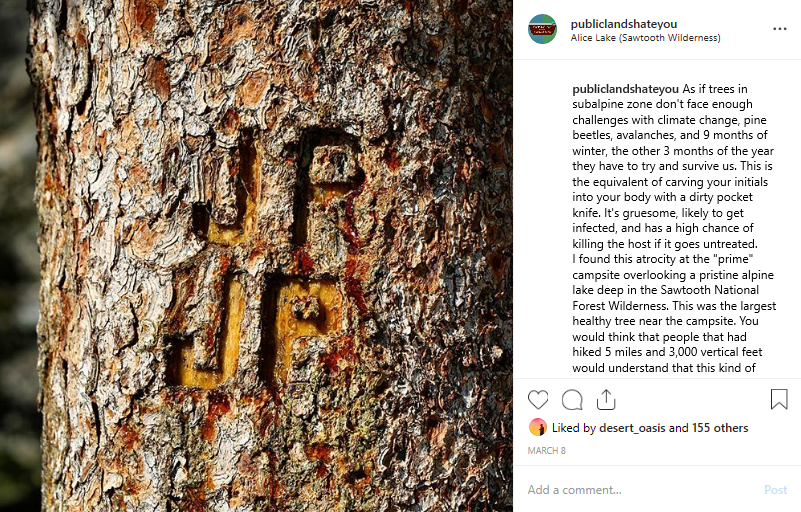

In the last five years, I’ve noticed a markedly increased rate of degradation of these public lands. Graffiti carved into the soft red stone of Arches National Park in Utah. Trash left 10 miles from the nearest trailhead in the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness in Montana. Broken bottles in my favorite Idaho hot spring. Illegal campfires on the shores of the Boundary Waters of Minnesota. Initials carved into the bark of birch trees in the White Mountain National Forest in New Hampshire. And most recently, the trampled wildflower fields in southern California.

I believe much of the blame for much of this damage can be squarely placed on you and me for sharing these places on the internet and social media.

~

Image: Instagram

Before the advent of social media, people (let’s call them Jim and Jenny, or “JJ”) may have started walking in their local forest preserve where they learned to stay on the marked paths, off trails when they were muddy, and perhaps they learned about another cool local hike. When JJ tried that new hike, they learned that flip-flops aren’t acceptable footwear for longer hikes, orange peels and apple cores should be packed out, and a fellow hiker shared some details about a cool hot spring up in the mountains. JJ’s visit to the hot spring that winter taught them that it’s important to check weather conditions at higher elevations, glass isn’t acceptable at hot springs, and then another hot springer told them about a rad hike in the local mountains.

The next summer, while completing that more difficult hike in the mountains, JJ learned that campfires aren’t allowed in the alpine zone, and that to avoid the crowds, you can backpack in and camp overnight. JJ then visited a local outdoor store where they bought a tent so they could do a longer backpacking trip. In addition to the tent, the sales person at the store made sure JJ had all the proper gear (some of which they didn’t know they needed) including a camp stove (no fires in the alpine zone) and trowel for cat holes (bury all human waste 6” deep and 250” from waterways).

You can see where I’m going here. This gradual learning process allowed people who were new to the outdoors to build up their responsible stewardship skills and ensured that the basic rules of the outdoors were learned and followed by the vast majority of people.

~

Image: Instagram

Nowadays, everyone has access to all of these amazing places with just a few clicks on the computer or swipes on their phone. They see a beautiful picture of a hot spring, say “that looks amazing, let’s go,” click on the geotag, find the location, maybe buy some basic gear on Amazon, and off they go after doing minimal, if any, research. Many of these people haven’t acquired the corresponding outdoor ethics that will allow them to be responsible users of our public lands.

Although these people may not break the rules and damage our natural wonders with malicious intent, the damage is done all the same.

I’m sure that “AW + RS” didn’t intend to kill that pine tree by expressing their mutual love in its bark, but they did. I’m sure whoever broke that bottle in hot spring didn’t do it on purpose, but it still cut my foot open. The campers who left a smoldering campfire in the backcountry probably didn’t realize that it often takes five gallons of water to put out a campfire, not just one Nalgene worth, but those embers still had a high probability of starting a wildfire.

~

Image: Instagram

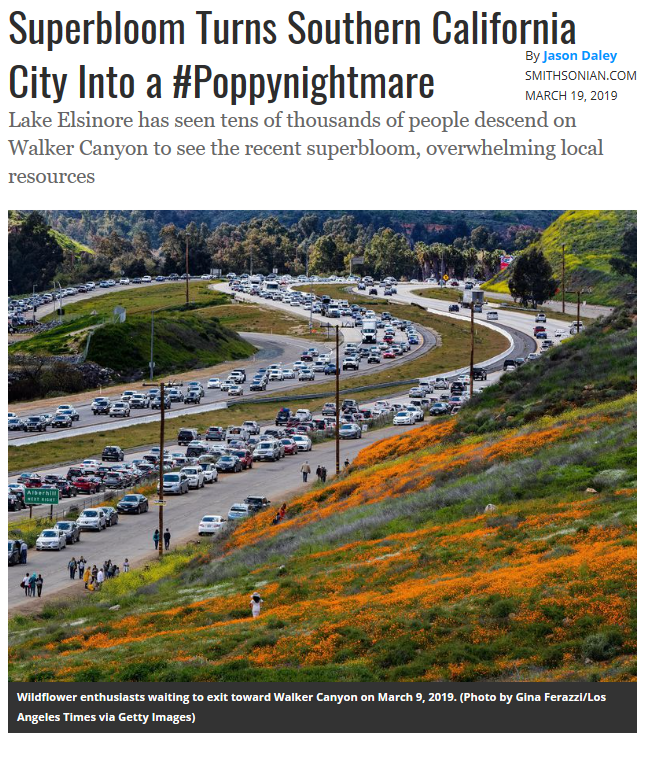

That brings us to our most recent manifestation of these issues, which has been occurring in the poppy fields of southern California. The only way to describe the “superbloom” there this season is epic—and word got out fast.

~

Image: Instagram

A few weeks ago, 100,000 people descended on the City of Lake Elsinore (population 66,000) to see the poppies at the Walker Canyon Ecological Reserve. The area was overwhelmed with people making the one-hour trip out from Los Angeles. Traffic on I-15 came to a standstill in both directions due to people parking on the interstate when the parking lot and local roads became clogged. A city employee was hit by a car directing traffic. The poppy fields were overrun with people who clearly didn’t know the slightest thing about the seven, Leave No Trace principles and apparently couldn’t read the numerous signs that said “Stay on the Trail,” “Leave No Trace,” and “Don’t Pick the Poppies.”

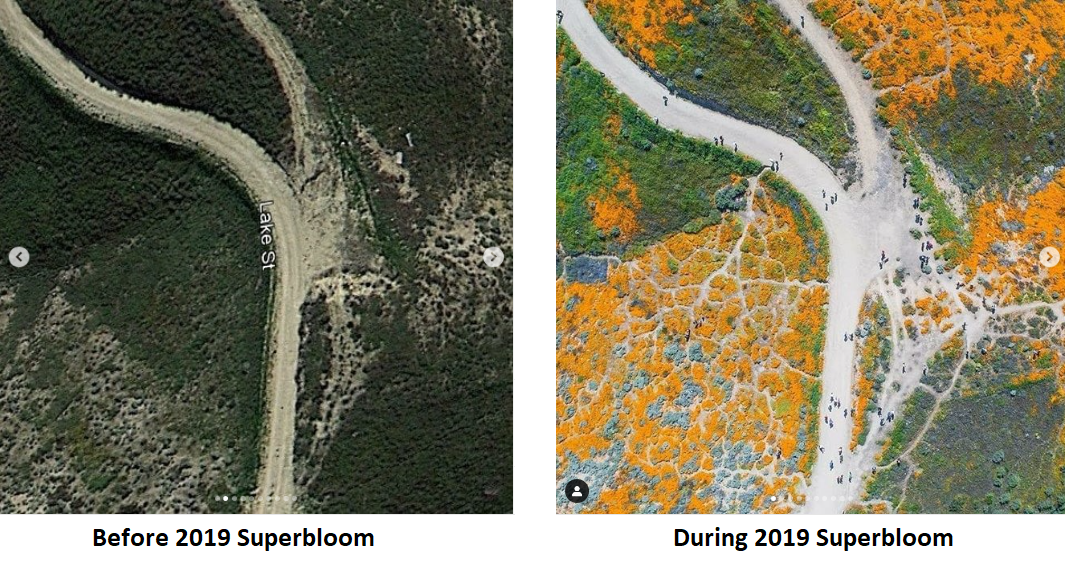

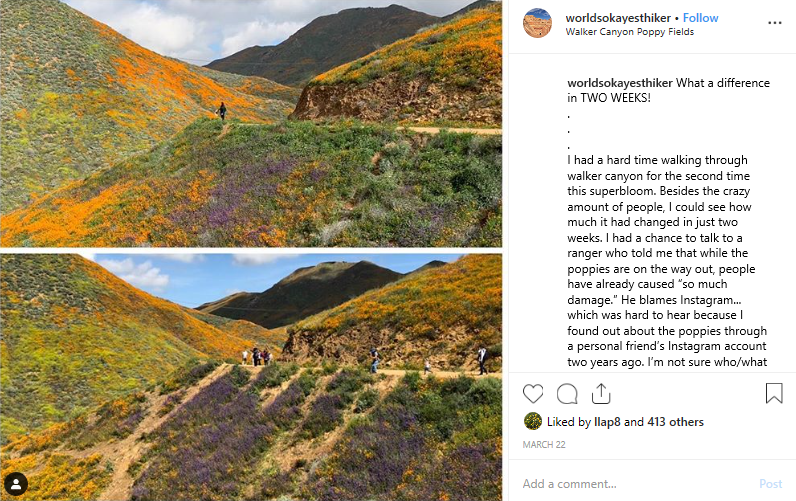

People were picking poppies, which is illegal on public land in California. People were going off-trail. Someone set up a tent for wardrobe changes between photoshoots. The before and after pictures tell the story—and it’s not pretty.

And for what? To share the “best” poppy picture (and super witty “Big Poppy” caption) with their 1,574 followers, probably only five percent of whom they’ve ever met in real life? Each person wants that untouched shot, so they go just a little bit further off the trail than the last person. And before long, we have new trails, which are often referred to as “social trails.” As more people use these social trails, the soil becomes compacted, losing its ability to hold water and air, making it so these new trails won’t support new growth for years to come. Before long, the previously unbroken wildflower fields look like a checker board.

~

Image: Instagram

There is a group even more obnoxious than people just trying to get cool pictures for their insta friends. These are the so-called “influencers,” or the people who have enough followers that companies pay for them to promote products. M&M’s. Campbell’s Soup. Clothing. Fake fingernails. Herbal supplements. I’ve seen it all. These “influencers” have thousands, and sometimes millions, of followers, and it seems like they will do almost anything to make a buck without a second thought about their actions and the message they are sending.

What makes these “influencers” think that it’s okay to commandeer the beauty of our public lands to advertise stuff while concurrently damaging those very same lands? The logic here is absolutely mind-boggling. Are they oblivious? Do they just not care? Are they getting paid so much that they can’t focus on anything except the $$$?

~

Image: Instagram

So, what has @publiclandshateyou been doing to improve the situation with the superbloom and outdoor ethics in general? We try to educate people in a productive manner with comments like “Please stay on the trail,” “Please don’t pick the poppies,” “Please practice Leave No Trace principles.” We encourage our followers to do the same. Sometimes people are receptive, acknowledge their mistakes, and take positive steps in the right direction. More often than not, people (and especially influencers) dig in their heels, make excuses, delete “negative” comments after labeling them as bullying, and block people who are trying to provide information. They think that they can just slide under the radar and continue to break the rules and engage in illegal behavior.

One of the interesting things about social media is that it’s a two-way street. People and influencers post the pictures in the hopes that other people will see them, and if they are lucky, an even bigger account will take notice, repost their content, and gain them more followers/fame/$$$ per post. If @youtube reposts your content to 18 million followers and spins it in a positive light, you’d love that right? But when @publiclandshatesyou reposts that same picture and points out that the content featured is illegal and should be removed, it suddenly becomes bullying.

~

Image: Instagram

Social media platforms are designed for content to be shared. If people choose to share publicly, they should be prepared to be held accountable for that content. “Influencers” promoting a product have an obligation to make sure they are doing it in a responsible and legal manner. That means looking up the regulations for where they are shooting to see if a permit is required for commercial photography, if drones are allowed, etcetera.

People with thousands of followers need to think about how their actions might be looked at, and what their followers might do in an attempt to replicate a photo. In sensitive areas, they should leave out the geotag. If someone really wants to know the location, they can send a message and you can make sure they are properly educated for their trip.

Bottom line, we are all influencers. Whether we influence one person, 100 people, or 100 million people. Your actions and what you share with others do have an impact on how other people act. We owe it to ourselves, our friends, and our families to act in a way that promotes good behavior and will help preserve our public lands for everyone’s enjoyment, now and generations down the line.

Remember, actions speak louder than words.

~

Image: Instagram

~

Read 2 comments and reply