The other day, I read an article on Fox News’ website.

It was about Elon Musk taking four coronavirus tests. (I was checking out Fox News to see their narrative on Trump denying the election results.)

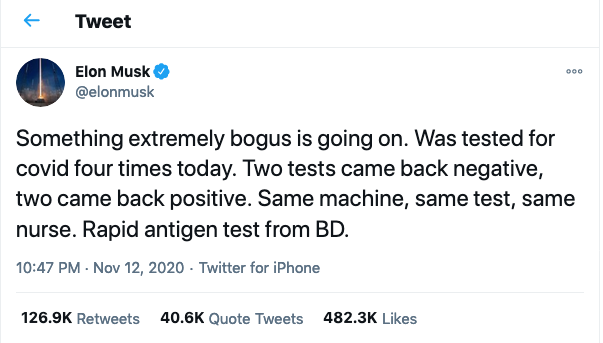

Two of the tests were positive, and two were negative, and Musk tweeted, “Something extremely bogus is going on.” An interesting choice of words.

When I Googled “bogus,” I discovered that it could mean “fake.” An obvious parallel to Trump’s position on most major news that doesn’t support his popularity (and the coronavirus pandemic has hurt his popularity).

Is Musk suggesting that COVID-19 testing is somehow fake?

Is he suggesting a conspiracy at work, undermining the perception that COVID-19 is widespread and spreading?

I don’t know. I don’t really care, actually.

When I brought up Musk’s tweet to a friend, he nodded and listened to me talk about it, briefly. I mostly was just wondering what was up, you know? Apparently, garnered from Musk’s little experiment (taking four tests at once), the tests are not always accurate.

If it were me, and I tested twice positive and twice negative, I would assume I was positive and quarantine. Beyond that, I didn’t really have an opinion about the whole situation since I don’t have any more information.

My friend said, “So you don’t think it was irresponsible for Musk to tweet that? You know, inciting conspiracy theories and COVID-denying and all that?”

I responded, “No. I don’t really care what he thinks. He can tweet whatever he wants. And people can choose to believe whatever they want.”

Then, I thought about it. Because I do think Trump is irresponsible with his tweets. Extremely. Beyond irresponsible, I think he is downright destructive and poisonous.

I think he incites violence, division, and he encourages people to express their rage in unsafe ways. Trump might have more influence than Musk, but that is questionable. Trump has 88 million followers on Twitter, and Musk has 40 million followers. Once you get over, say, 30 million followers, I think it’s safe to say your influence is far beyond the reach of Twitter.

Case in point: I didn’t read Musk’s tweet on Twitter. I read it on Fox News (and counted 23 news sources that reported on his tweet). That’s famous. That’s influential, potentially.

However, one could also say that Trump’s position as president of the United States gives his tweets more clout, more ground to stand on, more influence. And I believe this is true.

What I have been contemplating since my friend’s reasonable question to me is:

If we don’t want people to have cultural influence, we shouldn’t give them a platform, or many platforms, for that matter. Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and more, have made fame and influence possible for anyone who seeks it, and even those who don’t.

The American obsession with being known is pervasive and has sprouted more platforms than we know what to do with. Fame, or having people who don’t personally know you know of you, is a sticker, if you will, on your wall of accomplishments in America. (It’s perhaps, in and of itself, the greatest accomplishment of all.)

And what is it? Remember when you were young, and what your friends thought about what you did was, like, really important?

Well, fame is the same thing. It’s a lot of people thinking you are cool. That’s basically it. Lots of people like you. Why they like you doesn’t seem to matter much to Americans.

The fact that Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley, two of the most influentially famous people in the history of America, died basically of suicidal drug overdoses is inconsequential. We still hold them up as successful. Why? Because we liked them, and by “we,” I mean lots of us. I am not saying we shouldn’t, but liking is a contagious disease.

When other people like someone, I am more likely to give them a chance. Was Marilyn that much prettier than everyone else? Was Elvis that much more talented? I’ll never know because popularity itself breeds popularity, and then fame becomes the identity of the person we seek to know.

We don’t just want their gifts; we want their shimmer of being adored by many; we want to know their fame.

America has a unique obsession with this. Other cultures may be filled with the same human species, but perhaps the lack of resources and opportunity has kept them from the same degree of fame obsession. Or perhaps it is a special cultural zeitgeist that created such an obsession here.

Our unique “every man for himself,” capitalist, independent, boot-strap-pulling-up-culture made people want to be “self-made,” which has translated to making ourselves the commodity. Our very self is the marketing, which frees us (we think) to be ourselves and not have to fit in to anyone else’s thing.

Plus, if everyone likes us, or most people, which is the very essence of fame, then we have been anointed as “okay.” The race is up, we finished, and we finished ahead. Rest, relax. It’s done, finally.

Maybe it is a youthful narcissistic wounding that makes fame the inevitable conclusion to a successful life in America’s eyes. We simply didn’t get enough attention when we were young, or the right kind of attention, and in order to compensate, we need it in droves.

Or, perhaps our love-withholding parents made us feel that only a grandiose expression of success would do, and so we hold ourselves and others to the highest of approval-rating standards. We only see famous people as successful. (Well, if they are merely rich, that might do as well.)

Our every-Jane-Shmane-gets-a-public-platform society has given a voice to whoever wants it. And, as it turns out, most of us do. And Trump is no different.

Many a friend has speculated to me that Trump didn’t even want to be president. He simply wanted to be a part of the popularity contest (the election) and then won on accident, suddenly becoming the leader of the most powerful country in the world. Oops. And instead of leading it, he continued to just, well, act famous. He tweeted all his opinions and constantly checked to see who “liked” them.

Trump is barely a businessman. He had millions dumped on him by his father, and he squandered large amounts of it, tripping into real estate and making money the way most of us do with buying and selling a home, except his “homes” were at a much higher scale and made much more money. In fact, many of them were hotels. And then, he wrote a bunch of books. Actually, he paid people to write them, though I assume a lot of what was in them were his ideas. (Did anyone read them?) And then, he starred in a television show. Basically, he was a rich guy who wanted to be not just rich but rich and famous—like most Americans. And we supported him.

I have said here that fame is when lots of people like you. “Like” in this context doesn’t have to mean they have an affinity for you personally. It simply means something is appealing about you. Maybe it’s actually that they don’t like you, and that in and of itself is entertaining.

How many people started watching the Kardashians because they were horrified that someone was filming a family for no reason and wanted to know what this disturbing cultural stain was all about? Then, in finding out that it was “all about” a bunch of people simply called “The Kardashians,” they were endeared to the idea that simple people could be famous and relevant. Simultaneously, by considering the fact that ordinary people (can we call Kim Kardashian ordinary for just a minute? I mean, she is really pretty and has nice fake eyelashes) can be famous, we made them famous.

We did the same with Trump. We all thought, “Can Trump be famous?” And by simultaneously turning on the TV and watching him, voila, he was. (Actually, he already was, but then he really was.)

And what does that mean? It means we all started watching and listening to him, even though he was the same guy he was before. A publicity person could more easily explain this kind of thing, someone who specializes in what it means to get people to think you are something important, perhaps more important than you actually are. I imagine it’s not a terribly difficult job since just getting the image of someone’s face in a public place can often do the trick.

In 2006, I read an article in Bitch Magazine called “Bring Me the Head of Danny Bonaduce: Cultural Complicity in Celebrity Narcissism.” The authors wove together the American obsession with fame and how it supports what constitutes a narcissistic personality in certain famous people. It pathologized fame and those who come to believe in their own fame as an attribute inherent to their personal identity and entitlement.

(She used Jennifer Lopez as needing flower petals in her dressing room and Eddie Van Halen requiring a bowl of M&Ms with the brown ones removed as examples of this.)

The author’s description of this special brand of narcissism is very relevant to our current situation and political climate:

“In 2001, the New York Times ran a short piece about a syndrome called acquired situational narcissism, a phrase coined by Dr. Robert Millman of New York Hospital, Cornell Medical School. He argued that the life of a celebrity is so profoundly abnormal. The excessive spoils can affect the celebrity’s psyche such that, in response, he or she develops a grandiose or omnipotent self-image, loses the ability to empathize, has an increasingly distorted view of his or her place in the world, and reacts with rage to real or imagined slights. In essence, Millman argues that the celebrity situation can create a pathology that looks like classical narcissism but is actually an adaptive response to an odd shift in one’s environment. The media and the public are complicit in acquired situational narcissism; celebrities respond to our worship, or even our derision, as we feed their distorted self-image.” ~ Beth Bernstein and St. John M.

Yeah, see what I mean? It’s really well-written (and disturbing). It points out that our addiction and obsession with fame and celebrity actually causes narcissism. And furthermore, it is causing narcissism in people we have intentionally given platforms to—to create their fame, sustain it, and exercise their resulting influence.

I have painted an ugly picture of fame and its seekers. However, it isn’t all ugliness and narcissism. One could paint Trump as an extrovert who has many creative ways of communicating with people—books, making lots of money, spending lots of money, running hotels, and starring on television. And, being president.

The problem is, we can’t ignore the other stuff—the obsession with popularity and the resulting psychological influence on both the popular person and their fans.

Perhaps Americans can wake up out of the haze of famousness and its hulking presence in our culture, but I don’t see how. Perhaps on an individual basis, through careful self-observation and self-insight?

But our desire for fame reveals the same conundrum that all the spiritual paths assert is our fundamental human Achilles heel:

That we are afraid to be nothing, to be no one, and it is in this very nothingness that we become free, for it is the truth of what we are, and everything else is a falsehood that we must work to maintain. But you can’t fake it—you actually have to face the truth of being nothing. There’s no way out of this.

And some famous people have said that fame is the perfect way to see this more clearly, because the bigger your public “self-hood” gets, the more potential for you to see how made-up it all is.

For many of us on the “watcher” side, we are stuck swimming in the soup of who has gotten so popular that we don’t really know for sure if we like them or not, only that they are interesting. We are compelled to watch, look them up, click on them, and listen to them. And isn’t everyone interesting, even Trump?

The best way to diffuse conflict, they say, is to not participate in the aggressive behavior. In other words, don’t feed it. Do something else. For Trump, our obsession with fame and social power has fed his desire for attention. All it would take is not responding, not paying attention to the attention hog.

But can we do it when we have created every possible platform for attention hogs?

If we think he is irresponsible, aren’t we even more irresponsible for giving up our right to make up our own minds?

We haven’t figured out how to balance our addiction to fame with what happens when we give people the power of fame. We pour thousands of hours into listening to and watching people, we give them our money and our precious attention, and then we complain that they misuse it. But we haven’t been conditional with our attention; we have been practically unconditional.

Perhaps kicking our addiction to famous people (or making people famous) would pull the rug out from under it all.

Or, maybe we just need to see how we think we hate it, but really, we love it, too. Or at least, we want it, or them.

And maybe in that seeing, we can also see how to become a more balanced people—a more balanced country.

Read 2 comments and reply