It wasn’t a secret.

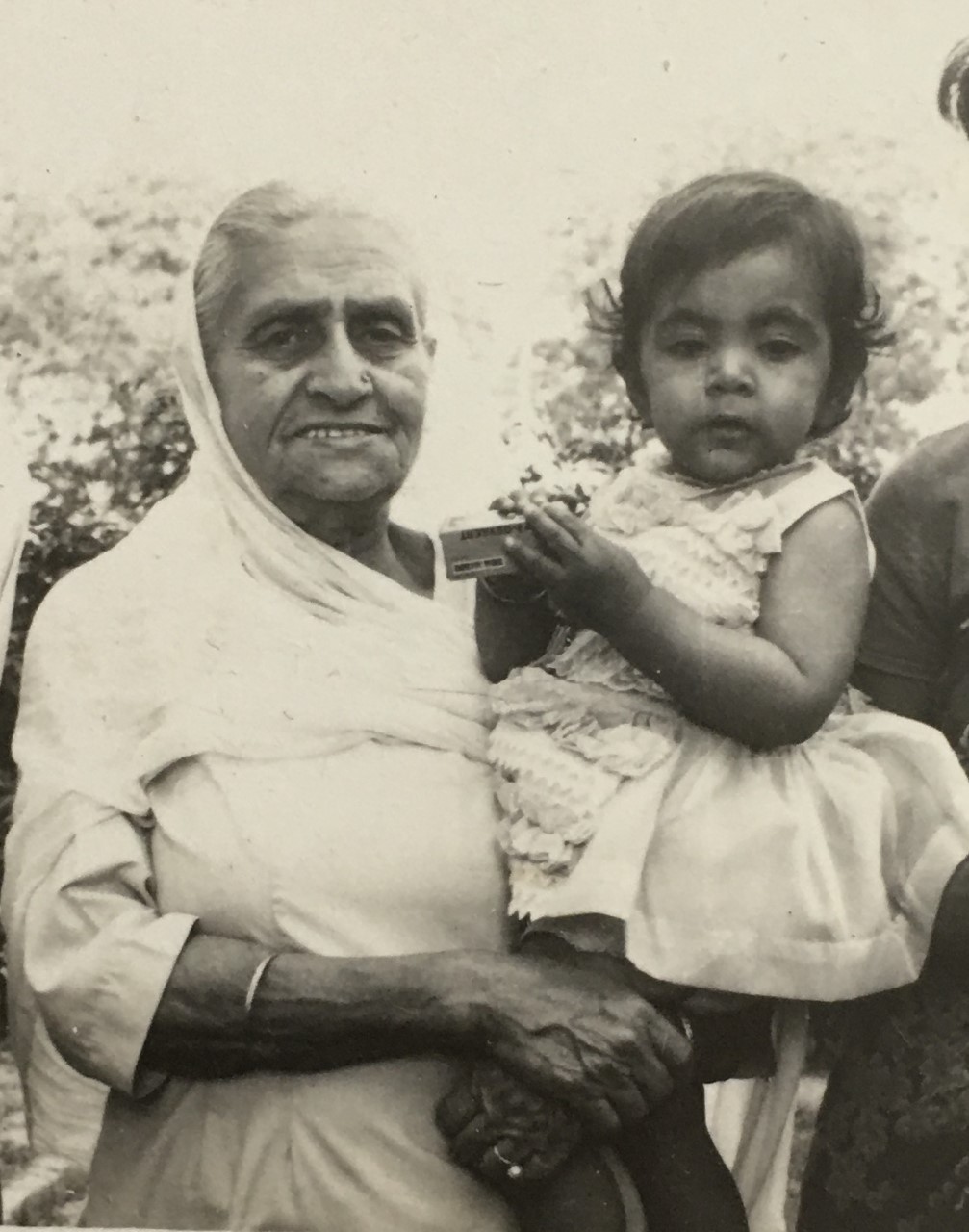

Everyone knew I was grandma’s favorite grandchild, and I was lucky enough that my paternal grandparents lived with us. When my mom and dad were away at work and my older sister in elementary school, I had her undivided attention. She doted over me.

She had been a vegetarian her whole life and had never touched anything nonvegetarian. In fact, when my grandpa wanted to cook mutton, she had a designated pan for him. But after I was born, she made eggs for my breakfast and fed them to me with her own hands; this was the strength of her love. She wouldn’t let the cook make them because that’s how precious and pure our bond was.

I called her “Chaiji,” meaning grandma in Punjabi. I napped in her bed with her most afternoons and even slept there some nights. My best memory is lying in her lap, upset, and she would stroke my hair and tell me “na ro puter,” meaning, don’t cry my child. Her magical touch always made me feel better.

Then, at the age of five, my parents decided to leave India, and we moved to Nigeria. With that one decision, we were separated only to see each other again after two long, sufferable years. When I turned seven years old, we moved to Kuwait, and I saw her every year over the summer holidays in Delhi.

I would begin the countdown to seeing her every spring somewhere around 80 or even 100 days with the excitement growing with each passing day. I remember the summer when I was 11 years old, we had just arrived in Delhi. I dashed up the stairs to the front door of my aunt’s house where my grandparents now lived. My aunt opened the door, greeting me warmly, and the only thing that came out of my mouth was, “Where is Chaiji?”

I flew past her and ran to my grandparent’s room. I hugged her so hard and so long and then finally came to greet my aunt who was quite upset at my disregard for her. It was the first summer I noticed I had grown taller than Chaiji. Still, that night she asked me to sleep with her, and I did uncomfortably in her single bed.

Chaiji passed away when I was 13 years old over the summer. I remember the unrelenting grief that I felt. Days after her cremation, I kept on crying. Eventually, even my mom told me to stop crying because so much time has passed.

It was the summer of 1990, and I was now 16 years old. My mom and I were in Delhi with my maternal grandparents for a few days longer while my dad and sister flew back to Kuwait. Then, on August second, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. Instantly, from being visitors, my mom and I became refugees.

As the hours turned to days that turned to weeks, we waited for news of my dad and sister. The stress was palpable in the house. Our lives were flipped upside down and with just the clothes we brought with us over the summer, we unknowingly began a new life. I hadn’t been enrolled in school, and I had no friends. I spent my days idle and anxious.

One day, my mom pulled out the only outfit we had saved of Chaiji, which had been safely kept at my nani’s (maternal grandma) house. All of Chaiji’s clothes had been donated upon her death, but this one piece had been kept as a memory. It was a plain, tailored, sage green kameez (blouse). There was no pattern, no embroidery, or design on it. It matched the simplistic nature of Chaiji. My mom told me to paint it as an activity to keep me occupied. I was no artist…that was my mom. Still, I took on the task just happy to have something to occupy my time.

As I thought of the design, my mind rushed to the million memories and the love I had for Chaiji. What was to be a fun craft task, began to feel weighed. What if I messed up? This is the only physical connection I had left to Chaiji. The summer was turning out to be an utter loss, and I was not prepared to lose this perfect and only connection to her.

Mom encouraged me and sketched the delicate white and yellow flowers to paint around the neckline and sleeve cuffs. I remember dipping the paintbrush into the paint and holding it for a while, afraid to set it down on the high-quality silk fabric. I was about to paint on the most valuable canvas on this planet. As controlled as possible, I made my first white dot and extended the brush stroke.

When I was done, the kameez didn’t look like it had been improved upon. But the sheer focus of the task helped me forget my situation. Chaiji had managed to ward off my stress even in her absence. I knew if she was alive, she would have worn this with pride over and over again.

Chaiji’s sense of fashion was different to the direction of fashion we have taken as a society. Some experts say we have reached a tipping point. It’s time to discuss what’s in our closets.

Imagine, if many of the pieces of clothing that you own had some kind of memory attached to them, or a story, or nostalgia. Would you be so quick to throw them out? This is part of sustainable (or slow) fashion…the exact opposite of fast-moving fashion.

Did you know on average that 500 billion T-shirts are made each year? Only 7.9 billion people inhabit this planet, and outside of the western world (where the bulk of the world’s population lives) T-shirts aren’t the everyday local wear for most women and many men. We don’t need to do any math here. It’s an exorbitant amount of clothing per person we are consuming. This doesn’t even take into account the jeans, shoes, purses, or dresses.

If you knew the garment you were wearing helped sustain the livelihood of the women in an underdeveloped country so that she could afford to take a day off when sick, or she wasn’t worried about having enough food, wouldn’t you be willing to pay her fair wages? If you knew she could make that T-shirt with focus and pride because she didn’t have terrible working conditions and somehow, she wasn’t voiceless or faceless, wouldn’t you pay a bit more? This is part of sustainable fashion.

When our clothing has meaning and connection, we are less likely to throw it out. Not only does sustainable fashion ensure fair wages, but it helps reduce pollution by lowering greenhouse gases and preventing artificial dyes from leaching into our waterways. The fashion industry also happens to be the second highest consumer of water, all of which can be reduced by changing our sense of fashion.

Social media and the rise of influencers have created a symbiotic relationship with the fashion industry. Many people feel the pressure to wear a different outfit every time they go out. But conscious consumers are demanding transparency from retailers and giving rise to secondhand clothing stores, repair, and upcycling.

What if there were impromptu drinks this evening by the poolside and the theme is a Hawaiian luau, could you rummage through your closet and find something? Yes? What if the theme was English Monarchy? Yes, you could pull that look together too? How about Arabian night? Yes? Only saffron-colored outfits with black polka dots? Yes, to that too? People, we need to talk!

So, you’re a value shopper? I get it. I’m one of them too. Wait, did the cost of those organic strawberries I picked up at Target exceed the cost of the T-shirt in my cart? There is another option to buying expensive sustainable clothes, and it’s called being on a fashion diet. COVID-19 has helped jumpstart it for a lot of us—let’s just keep the momentum going.

Commit to not shopping for three months, or even six months. After all, you have enough in your closet for the next 11 impromptu themed parties anyway.

Next time, when a friend notices we wore the same outfit twice on social media, instead of being mortified, feel pride just like Chaiji would have. We can tell them about the story behind the outfit or our changing habits. Fast-moving fashion is going to put you out of fashion, people—it is so yesterday!

~

Read 23 comments and reply