*This is an excerpt of the book Leaning toward Light by Tess Taylor | Hachette Book Group.

~

A year into the pandemic, when everything seemed very grim, Hannah, a friend who I knew from my time working at a farm in the Berkshires, called to ask if I would like to build an anthology of contemporary gardening poems. “People are taking such solace in gardening now,” she told me.

Of course, the day she called, I’d been out in our front yard plot myself, clearing out peas and putting in zinnias and talking (still at a distance) to people wandering by who seemed curious about gardening.

I’ve been a gardener since my parents took me as a baby to their community plot in Madison in the late 70s. As well as working the year on the farm, I’ve gardened in Boston and Brooklyn and taught gardening to youth in a community garden in West Berkeley. I’m a poet, too: and my poetry practice is equally sustaining. For me, gardens and poems are each places where we discover our attention, excavate our imaginations, and come into deeper community with wider human and non-human worlds. I was delighted that Hannah was offering me a way to allow my poet self and my gardening self to work together, in one place.

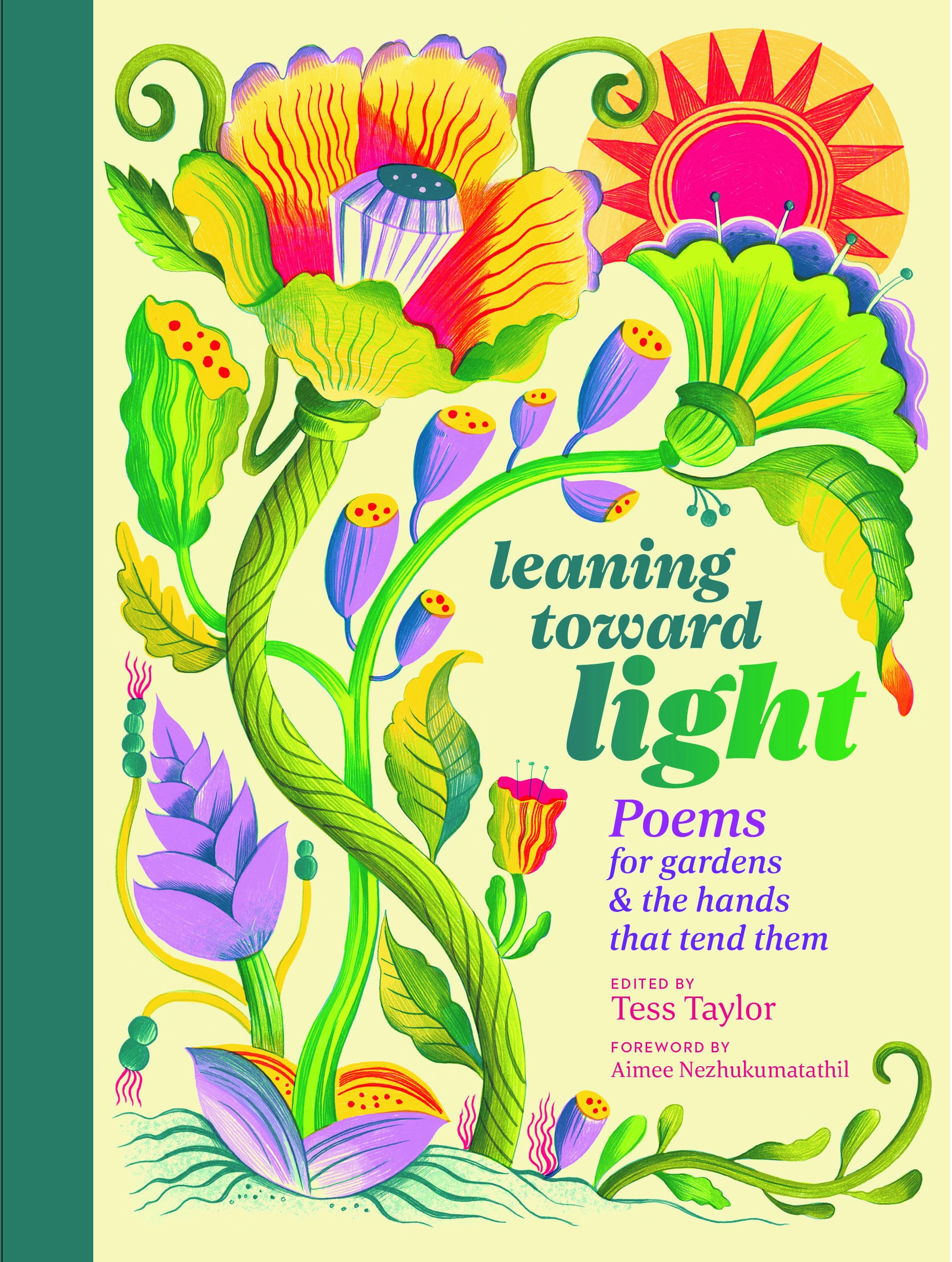

We started to brainstorm. There are plenty of ye-olde gardening anthologies out there. They are lovely. But this gardening anthology had to be diverse, for a moment where we are living with climate grief, when we feel the heavy knowledge of losing the planet, when we might just garden to figure out how to persevere. This book had to be about the diversity of people and plants and animals that can come together when we do lean toward attention and repair. It had to hold our grief, our reverie, our hope for justice and abundance. I worked fairly steadily for two years. I got to collaborate with some of the best poets writing today. And now Leaning Toward Light, Poems for Gardens and the Hands that Tend Them is available for order, having been released on August 29.

I don’t claim that I’ve found an answer to our many woes. Poems and gardens, are, by themselves, small things. They may seem sidelong to the “real” action of our troubled, often violent world. Sometimes it’s hard to know if your tomato plant matters. “No poem ever stopped a tank” said Seamus Heaney in the middle of the Irish violence known as the Troubles. In climate terms, we also know this is true: if big polluters and governments don’t make radical change, any one choice to compost or plant bee-friendly lavender or remember reusable bags or skip the dryer and hang out clothes on the line; to bike instead of driving, doesn’t really amount to a hill of beans.

But we do come to poems and gardens to rediscover the world, and ourselves, to root both our sorrow and our joy. We come not because we save the world from its peril by our tender and close attention, but because in that attention we at least sidestep the peril of our own numbness. We don’t start to care about things because we love them, says the thinker Allison Gopnik: We learn to love in the acts of offering our care. Poems and gardens offer us sites to learn and practice love for one another and for the smallest things of the world: a butterfly, some wild fennel, an unexpected volunteer pumpkin plant. We also see the ways that life (something not of our making) has its own work through and around us. We come to these spaces to learn more attentive relation to our own lives, now, on this endangered planet.

I garden on the front yard of a small bungalow in a formerly working-class town north of Berkeley, and mostly, I suppose, my scrappy front yard garden could seem ornamental. But it’s a place where I notice both pollinators and community—hummingbirds, butterflies, bees—and people who stop either asking to learn more, or neighbors who want to share plants, or simply passersby who love seeing the zinnia and amaranth along the median strip.

What is the value of our mindfulness? What is the value of the time we spend dreaming in poems? What is the value of a few pollinators? What value in the tendrils of community we send toward one another? Earlier in this essay I used the phrase “hill of beans.” The phrase—which is supposed to denote something of little value—also has a long history in it. It calls up the image of ourselves as a people who grow and scratch and heap up and tend the earth around us. The phrase reminds us to mound a bean plot as we seed the plant, and that beans actually grow better in mounded groups that vine up together on trellises, out of those hills. (The root of poem, by the way, is also “to heap up). Anyway: how many beans (how many poems) can grow on a well mounded hill. Enough for many meals. How incredible the bean is, the protein rich seed, the legume, its long history as a basic food that can sustain many people with a light footprint on the earth. How well beans grow with squash and corn, those three sisters who both make complete proteins for our bodies and re-nourish the soil with their rhizomes. It turns out I value a hill of beans quite a lot, and with them the soil, the work of food, the labor of tending, the many people on this earth who need, in so many ways, to be fed.

~

GENINE LENTINE

Interview with the Pear Tree

When did you start making pears?

What is a pear?

(She runs her fingers over one

hanging on the branch.)

Mmm. Yes. It began

before I could be seen,

when the great body rang,

striking, for the first time, the earth.

Over the long day, it lay in the sun,

and the birds came, and the flesh

fell away until all that was left

was the seed. Maybe it was

when the moon swelled

the seed, maybe

when the first true

leaf quickened.

Did you always know you would make pears?

I wouldn’t know how not to.

What is your process?

I let the leaves

come to the branch

and when the bee is at the

blossom, I listen.

Is dormancy difficult?

Dormancy?

A period when nothing happens.

(The tree pauses.)

I’ve never had one.

What about drought?

I spread my root hairs and wait.

Do you ever doubt?

When the bud breaks the green wood.

Do you ever think of making apples?

What is an apple?

Could you describe the kind of pears you make?

(A ripe pear drops into her upturned hands.)

FEDERICO GARCÍA LORCA

August

August.

The opposing

of peach and sugar,

and the sun inside the afternoon

like the stone in the fruit.

The ear of corn keeps

its laughter intact, yellow and firm.

August.

The little boys eat

brown bread and delicious moon.

TESS TAYLOR

Green Tomatoes in Fire Season

There is smoke in the air

when I go pick them.

I go despite panic, also because

inside I’ll make chutney.

For an hour or so, I unlatch them.

It is late fall. They will not ripen.

Firm pale green skins,

fine-coated in ash.

Our fire season goes all autumn now,

though today’s fire is not

yet near to us.

But the green tomatoes: I love their pale lobes.

Tonight, god-willing,

we will fry some with cornmeal & fish.

Inside the air purifier whirs:

I will boil them with molasses & raisin.

Jar them for friends & the winter.

Disaster, we say, meaning bad star.

These are good green stars,

this is also their season.

Mask on, I bend & bend to the vine:

I bend & salvage what I can.

~

Please consider Boosting our authors’ articles in their first week to help them win Elephant’s Ecosystem so they can get paid and write more.

Read 3 comments and reply