I was a child of the 80s, raised by a former hippie mom and largely in awe of my Reagan-era Aqua Net, permed, hard-partying and decade older sister.

Heavily influenced by the colliding cultures of both the 60s and 80s and the bridging “dope generation” of the 70s via both media and interpersonal relationships, I was also a teenager in the 90s—in Seattle, no less—and it takes no great leap of the imagination to surmise the role the grunge era played in my pubescent development. Images of “heroin chic” and the Seattle-centric, heroin-addled rock stars went viral before high speed internet, or even computers, were commonplace.

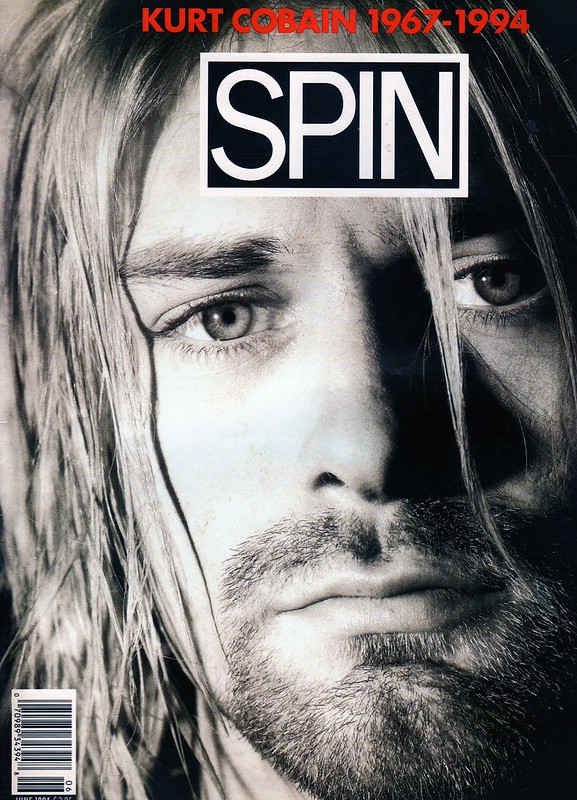

Between my mother’s Hendrix, Joplin, and Doors albums, my sister’s bedroom walls plastered with images of Motley Crue, Metallica, and Guns N’ Roses, and my own adolescence spent plastering black and white magazine adds of a doe-eyed Kate Moss on my walls as my peers plastered posters of close-ups of a scowling Kurt Cobain and we screeched, bellowed, and moaned along to every track on Hole’s Live Through This CD, one message was cemented as irrefutable in my young and creatively fertile mind:

Art had something to do with drugs and drugs had absolutely everything to do with art.

I’m going to make this clear right from the start: when I refer to drugs in this piece, I’m referring to what are concerned hard, illicit narcotics—heroin, cocaine, crystal meth, fentanyl, and even alcohol when chronically abused.

Though I’ve personally chosen to be drug free for a decade, I’m an ally to the plant-based drug community and I’m excited for the exploration and legalization of hallucinogenic substances as a therapeutic tool. I live in a state where marijuana is legal and I think it’s a wonderful medicinal herb.

I’m also not against the use of prescription drugs for pain, in spite of prevalent controversy and negligence. Nobody should suffer needlessly. I also realize that illegal drug users are frequently using to alleviate psychic and physical distress, and self-medicating as a result of trauma. And here in America many people do not have access to substantial medical care to acquire the treatment they need in a legal capacity—I know that because I experienced it.

Here I am specifically referring to a lifestyle and culture of chronic, debilitating drug use that became central to the identity of individuals and entire communities, if not generations.

When I was growing up, there was undeniable glamour surrounding the hedonism of bygone eras: the psychedelic, hippie love-ins that we heard about from our parents or caught stilted footage of on rabbit-eared television sets were happy scenes, idealistic, creative, and hopeful as uninhibited people made flower crowns and painted symbols of innocence on one another’s faces. They tuned in, turned on, and dropped out. This was drug use with a purpose and the intention was to overthrow the confines the patriarch—“The Man”—had and still does impose on us.

There were epic marches on Washington and images of iconic musicians taking the stage at Woodstock. Sure there was tragedy that ensued as drugs with more addictive properties than “grass” and acid insidiously found their way into the festivities and brilliant artists were taken from us far too young, which would become a tragic theme, but the starving or svelte and always sophisticated inebriated artist archetype was on full display in our collective memories as The Chelsea Hotel, the denizens of Andy Warhols Factory, Greenwich Village, and gritty East 42nd Street in New York, the colorfully non-conformist San Francisco, and Glitzy Hollywood Boulevard continued to marry images of high art with high humans throughout the 70s.

And it wasn’t just musicians! Drugs fueled the masterpieces of brilliant painters, authors, actors, photographers, designers, and grind-house directors as well. As a writer myself, I could fancy myself as a future William Burroughs, Hunter S Thompson, Jack Kerouac, or Allen Ginsberg, hunched over a mammoth typewriter with a cigarette dangling from my lips, surrounded by self-aware bohemian types and multidisciplinary artists in pay-by-the-week motels or squatting in abandoned buildings because the beauty and truth of art was our true sustenance.

These images were real to me—they were inspiration and a promise of freedom of movement and speech and thought.

The bohemian dreams were soon pushed into the recesses of our consciousness as the “bigger is better,” unapologetically fiscal, and let’s get physical images of the 80s shredded their way into our world via television, radio, magazines, billboards, and movie theaters. What we also witnessed was an apparent diametric opposition of roles in the form of the rebels versus the yuppies, which was not in fact new at all and has been part of the pop culture narrative since the squares and the greasers of the 50s.

You had every John Hughes movie spoon (or is it fork?) feeding you this sugary, binary narrative cake: the preppies as privileged nepo babies with no souls and an easy trajectory to Ivy League schools and the Hamptons with nary an original thought, whereas the New Wavy punks from the wrong side of the tracks were walking lexicons of underground music who hung out in dingey, used record stores and moonlighted as DIY couture designers. As images of both tropes inundated our screens, cocaine saturated our culture and as far as anyone could tell, the sharply dressed, puckish rouges on Wall Street and the one glove wearing, avant-garde posing, fringe dwelling wavers were all partaking in the chic white substance that represented superficial image more than literary style.

And then came heavy metal, with their conspicuous heavy drug use and tales of self-administered, near-death experiences in trashed, five-star hotel rooms. Oh the excess! We learned that supermodels and playboy models alike flock to the walking car accidents that are chronic, progressed alcoholics and addicts, and that nothing was sexier than reckless endangerment, driving while intoxicated, and flaunting one’s wealth and success by ingesting it. The harder they partied, it seemed, the more potent the men and the more pretty the women.

And then there was Grunge.

At this point, drug use was no longer a subculture but a commercial product, the lyrics blatant rather than laced (pardon the pun) with innuendo. Though not as flagrantly glamorized as it had been in the past, superiority complexes were out and inferiority complexes were in as sulking, emaciated musicians complained about the burden of their own drug abuse, which ironically served as a sirens song rather than a warning.

Drug users still represented the antiheroes, the non-conformists, the independent thinkers, and licentious sex symbols as they had since the 60s, whether they wore bell bottoms, platforms, leather jackets, or flannels. Who wouldn’t identify with the outcasts, the social reformers, the artists?

All of this in spite of the ever-increasing numbers of public casualties, both living and dead. Some got hit by that train and died in front of our eyes, effectively breaking our hearts, while others got run over by that train and survived, in a world of hurt. Both leaving apocalyptic levels of destruction in their wake.

All of this continued to add to—rather than rightfully subtract—from the thrall of drug abuse.

In the 90s, I fell into what I consider a trap of drug abuse because I was misguided and curious and traumatized and surrounded by the normalization of self-medicating, and it was a perfect storm for a 13 year old, neurodiverse, and hormonal girl from a dysfunctional home in Seattle in 1995.

I had my copy of The Outlaw Bible of American Poetry in hand, and I wrote cliche poetry in my (at the time) cutting edge hemp journal. My leather jacketed boyfriend bought me a ring with a secret compartment to keep acid tabs, we rented indie films both old and new from an indie video store, and I both watched and read A Clockwork Orange and Requiem For a Dream.

I had no desire to be a drug addict and every desire to be an artist—and as far as I knew, they were synonymous.

People handed me paperback autobiographies on Nancy Spungen and Gia Carangi and told me they feared I would “end up like” these beautiful, cool women. I didn’t completely miss the point but I did resort to experimenting with intravenous drug use after several years of intermittent but heavy use of stimulants and alcohol. I did a few stints in rehab, I went to juvenile jail, I sat in doorways in the pouring rain in hoodies anxiously awaiting the always fashionably late drug dealers.

Did I make great art in that time period between 1995-2000, age 13-18?

Absolutely not. But I tried and I wrote and I consumed art along with my coke and meth and 40 ounces of malt liquor, most of the time. I was also surrounded by people who had similar artistic notions and delusions, at first and then later only occasionally. And then I was around people who wanted to get high. Period. Not get high and write a culturally redefining novel, not get high and make picket signs, not get high and paint boundary-pushing fetish nudes the likes of which you’ve never seen before. Just. Get. High.

Hearts were broken instead of barriers, possibilities closed instead of opened. Children lost contact with their parents and parents with their children. People lost their homes, went to prison, or were assaulted, or worse, killed or overdosed. Again and again.

But this is not new information. We’ve all been long acquainted with the seedy underbelly of the hip underground and the true cost of excesses. Has the cultural zeitgeist been called out for the significant role it has played in this mass destruction?

Fortunately, artists are now more comfortable writing or singing or creating content around their experiences with recovery and healing. I think it’s imperative to keep it going and not fall back into the persistent lie that drugs are necessary or even conducive to artistic expression.

After spending years drug free as a young home maker, I resorted to drug use as a means of self-medication in 2012, when I was 30, and what I experienced and witnessed on the streets and in the drug scene was about as far away from art and peace and love as you can get.

If you drop acid or do MDMA or ketamine or Ayahuasca in therapy or at a festival or orgy to lower inhibitions and heal or connect with yourself or the universe or others or create in any medium or simply chill, I genuinely think it’s a beautiful thing, even though I choose not to partake.

If you need opiates for your back or benzodiazepines for your anxiety and can take them without abusing them then I applaud you and modern science for reducing human suffering when possible, and I will not hesitate to take medication to alleviate symptoms that interfere with me living a higher quality of life.

But what I saw in 2013 was people taking drugs that rapidly and dramatically reduced their quality of life. People living under bridges, not beading necklaces, weaving baskets, or writing the next great American novel but rifling through piles of garbage for anything they could sell for their next fix, shivering in freezing temperatures at night, standing in food bank lines that wrapped around the block.

I’m 41 now, and as I stated I have a decade of being drug and alcohol free. I could not ever go back to the lifestyle itself or the unconscious illusions I held that encouraged it. They have all been shattered like my mother’s car windows when my addict sister had her boyfriend break them all. Like my car window when a man I was dating broke it in a paranoid rage during a meth-induced psychosis. Like the glass meth pipes that I accidentally broke and thus induced the rage of the men I’d been smoking with who looked at me like I had broken the Hope Diamond rather than a cheap and commonplace pipe used to smoke cheap and commonplace drugs made of inarguably toxic chemicals.

Today, Seattle is well into heroin and meth epidemics and newly into a fentanyl epidemic, all of which are undeniably connected to skyrocketing trends in homelessness and deaths rather than guitar solos and arthouse cinema.

Layne Staley and, of course, Kurt Cobain are long dead, along with many of their predecessors and peers.

Art, to me, has always had the objective of facing and communicating the truth in order to free us from the bonds of deeply entrenched, socially conditioned deceptions. Art challenges popular culture, dogma, capitalism, moralism, and patriarchy and in so doing gives us a new lens in which to see the world and one another. However painful that reckoning may be, it’s one that leads somewhere: higher consciousness or catharsis for the individual or the community.

Drugs manufactured or harvested and trafficked with the sheer intention of turning a profit reflect the nature of capitalism, not research, connection, or enlightenment, just as drugs taken with the intent to evade the truth rather than the intention of finding new ways to look at it reflect self-deception rather then self-awareness.

Sometimes, when we begin using external substances to feel better we do so with intentions as pure as the substances themselves but it can all too easily turn on us as the drugs get stronger and cheaper, the distributors greedier, and the government more unjust and harder to navigate. Today, rather than overthrowing The Man, drugs are rendering people more at his mercy than ever.

~

Please consider Boosting our authors’ articles in their first week to help them win Elephant’s Ecosystem so they can get paid and write more.

~

Read 5 comments and reply